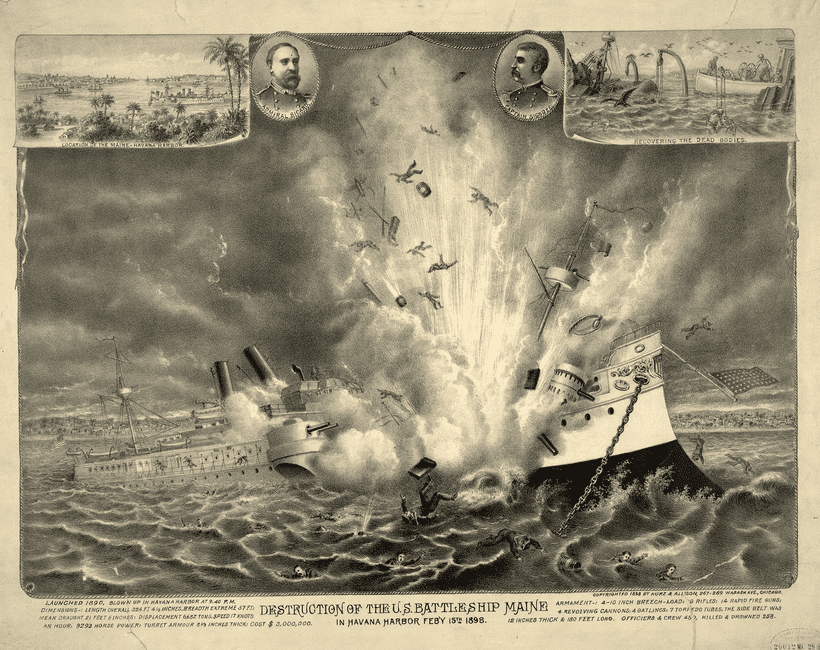

At 9:40 the night of 15 February 1898, a massive explosion sank the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana Harbor, Cuba, killing over 260 men and whipping the American public into a war frenzy against Cuba’s colonial overlord, Spain.

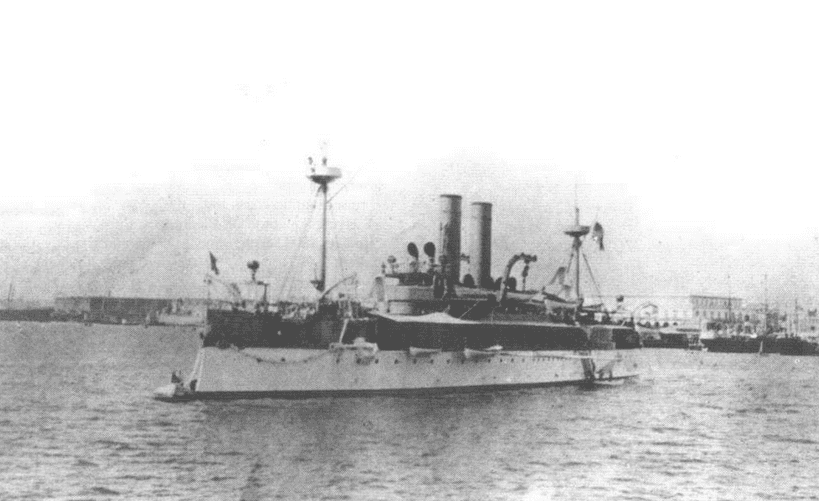

The battleship had entered Havana Harbor on January 25 to protect American interests in the face of a popular insurrection on the island against Spain’s harsh rule.

The cause of the explosion remains a mystery to this day, despite four separate investigations, but the verdict with the most impact was the conclusion of the U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry, announced on 28 March 1898, that a mine had sunk the Maine.

This was all the confirmation the U.S. public and press needed to demand a war against Spain, and the popular cry “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” reverberated throughout the land.

Americans had become increasingly upset with the harsh measures the Spanish military was using to suppress a Cuban insurgency that had been fighting for Cuban independence since 1895. To prevent Cubans from giving aid to the rebellion, Spanish authorities rounded up villagers and placed them in fortified areas. The reconcentrados, as they were called, suffered from unsanitary conditions and lack of food, and thousands of them died.

American commercial interests, especially the sugar industry, were concerned about Spain’s inability to maintain stable conditions in Cuba. With the public, newspapers, and business community all calling for action, a reluctant President William McKinley could not stem the war fervor. After Spain rejected an ultimatum to leave Cuba, Congress declared that a state of war with Spain had existed since 21 April 1898.

Some historians say the Spanish-American War was an honorable affair, fought by altruistic Americans to free the oppressed Cubans from the yoke of Spanish colonization. Others say this was America’s foray into imperialism: its first war fought not to consolidate its holdings on the North American continent but rather to gain overseas possessions.

Here are two newspaper articles helpful in understanding the war fever gripping the American public. The first, printed the day before the USS Maine blew up, is a sermon delivered by a reverend to stir up his congregation. The second is a news report of the disaster in Havana Harbor.

Here is a transcription of this article:

A Plea for Cuban Relief

Rev. Allen E. Cross Speaks Earnestly for Aid to the Suffering Islanders

Rev. Allen E. Cross, in his sermon yesterday morning at the Park church, spoke as follows upon the subject of Cuban relief:

Not so far from the shores of America as Boston from Springfield is the island of Cuba, and upon it, like an incarnate prayer to God for pity and vengeance, lie the bodies of 200,000 men. Were these bodies slain in battle? No! Did they die of their own rashness? No! Was it by nature’s famine? No; for the soldiers about them did not die of any famine. What, then, brought them to this end? They were starved like cattle in the pens of crowded towns, driven there and herded, lest they feed their Cuban brothers in arms… But what of this. We can do nothing for the dead except it be to punish their murderers. Ah! but the living! – more than 200,000… More in peril of a like death! The facts are admitted by Spain herself. At last, at last, the terrible secrets are disclosed, and the horror is set before the eyes of the world, and the hearts of the world are asked for pity! An appeal has come to me from the New England Cuban relief committee. It is a very remarkable document in its frank disclosure of facts and in its straight summons to our hearts for help. It comes to supplement the Christmas appeal of our president for the same end, and to it are affixed the names of some of our most trusted New England citizens.

Yet is it not strange that such a reinforcement of the president’s proclamation is needed, and so long after, and from private citizens? Why has not this appeal been better heeded? Perhaps it is because in the hearts of American citizens there is a kind of deep rebellious protest that the suffering which America has failed to prevent by diplomacy her citizens should be asked to relieve by charity. Nay, more – there is a stronger protest, that what Spain has failed to do for her loyalists (for they are such, most of those men at least, or they would be in the ranks of the insurgents) is demanded of us in the United States. But Spain is poor, you say; yes, poor, poor Spain! She can spend $640,000,000 to bring men into misery, but not a dollar to bring them out, or to relieve that misery. Ah, she will be condemned by the ages as much for her inhumanity to Cuba as for the horror of the Inquisition.

The kind of relief that Americans now desire for the Cubans is not in food, or coin or clothing, but in bullets and bayonets. The unfortunate De Lome has exposed the lying scheme of autonomy, and the duplicity of the proposed commercial treaties. The end draws on! The fall of stocks or the rise in sugar cannot avert it. The ultimate form of Cuban relief must be from the guns of the Maine and the Montgomery.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Maine Blown Up

253 of Her Crew Missing, Most of Them Being Undoubtedly Lost

Only 42 of the Entire Ship’s Company Escape without Injury

Spanish Treachery Suspected, but Accident the Probable Cause

This city, in common with every other portion of the United States within reach of the telegraph, was thrown into a state of excitement at an early hour this morning by the report that the battleship Maine had been blown up in Havana harbor during the night. The first advice of the awful affair was received by the News in a special telegram from its Washington correspondent as follows:

Laid It to the Spaniards

WASHINGTON, D.C., Feb. 16. – The U.S. ship Maine was blown up at Havana by Spanish treachery. One hundred lives were lost.

Board of Trade Reports

Within a few minutes after this time the wheat men of the city received advices to the same effect from their correspondents at Minneapolis, but although there was some inclination to attribute the disaster to Spanish deviltry there was no direct charge to that effect.

The Associated Press

About 9:30 a.m. the Associated Press forwarded the following telegram to the News from their headquarters at St. Paul:

ST. PAUL, Minn., Feb. 16. – The battleship Maine was blown up by an explosion during the night in Havana harbor and is a total wreck. Probably a hundred men were killed and many injured. The cause of the explosion is not known.

Calms Resentment Somewhat

This telegram, which placed a doubt upon the origin of the disaster, had a mollifying effect upon the public, but many were loath to believe the fanatical population of the Cuban seaport were innocent of the outrage and wholesale murder of innocent men. The war spirit was rife and there is not a doubt but that two-thirds of the able-bodied men of the city would have volunteered at any hour of the day to enlist in a war of extermination against Spain. Almost everyone believed for a time that the disaster was equivalent to a declaration of war, if a state of war did not really exist, and while all deplored the loss of life and the destruction of one of the bravest ships of the new navy, there seemed to be a general feeling of grim satisfaction that at last the United States was about to wipe the curse of Spanish domination from the new world. The latest information regarding the explosion was the following telegram to the News from the Associated Press, which placed the loss of life at 253 and the number of injured at 59, and attributed the affair to accident:

The Captain’s Account

WASHINGTON, D.C., Feb. 16. – Secretary Long has received a dispatch from Captain Sigsbee of the Maine saying 253 of the crew are missing and that most of them are undoubtedly lost. Fifty-nine were injured and forty-two were uninjured. Indications point to an accident, though just how it happened is not known.

Part of the wounded men of the Maine were taken on board a Spanish war vessel for treatment. Washington authorities ask the public to withhold judgment pending an investigation.

Indefiniteness Significant

The indefiniteness of this statement on the part of Captain Sigsbee is decidedly significant and lends color to the theory that the Spaniards are to blame and must be called to account. Diplomatic usage would make the ship’s officers slow to attribute the loss of the ship to Spain in the absence of positive proof. If the dastardly act can be traced to either the Spanish government or to citizens of that country there is no doubt war will result. If the act was done by citizens, Spain will be held accountable for the loss of the ship and for damages for the lives of the crew. This sum would amount to many millions and would be beyond the power of Spain to pay. In that event war only could result, as this government would probably demand possession of Cuba by way of indemnity. It is hard to believe, however, that the vigilance of the Maine’s officers was such as to permit the Spaniards to commit the deed, although it may have been done by a submerged torpedo.

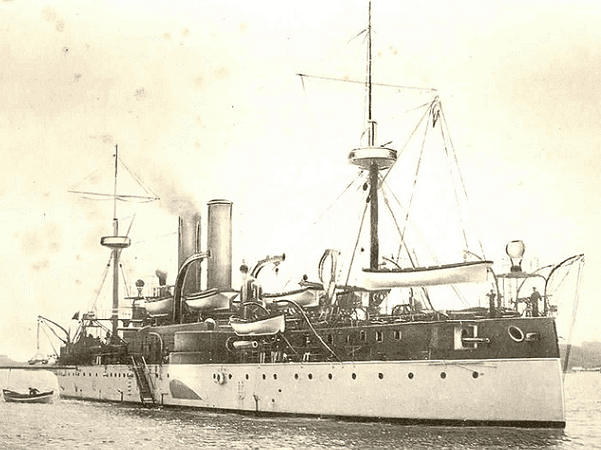

Something about the Ship

The Maine was a battleship of 6,682 tons displacement, 318 feet long on the water line, 57 feet wide, and had a mean draught of 21 feet 6 inches. Her engines were 9,293 horsepower. She carried 4 ten-inch breech loading rifles, [plus 6 six-inch guns – ed.], besides 7 six-pounders and 8 one-pounders. Her complement of hands was 29 officers and 370 men. Her cost was $2,500,000, and her keel was laid in 1888.

Nothing like a similar disaster has occurred in naval circles for many years either in war or peace, with the single exception of the sinking of the British war ship Victoria, by a sister ship, while maneuvering in the Mediterranean a few years ago. A complete investigation is [a]waited by the American people with impatience and anxiety.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the Spanish-American War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.