Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega searches old newspapers to learn about a sensational murder and trial early in the 20th century that captured the public’s attention. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

“The Trial of the Century!” Headlines seem to scream that phrase more than once in a century – yet it’s only a matter of time before that trial is forgotten and a more infamous trial takes its place. The first “Trial of the Century” for the 20th century was that of the June 1906 murder of noted architect Stanford White by millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw in revenge for the “honor” of his bride, Evelyn Nesbit.

It’s an age-old story of sex, jealousy, excess, money, and of course, murder.

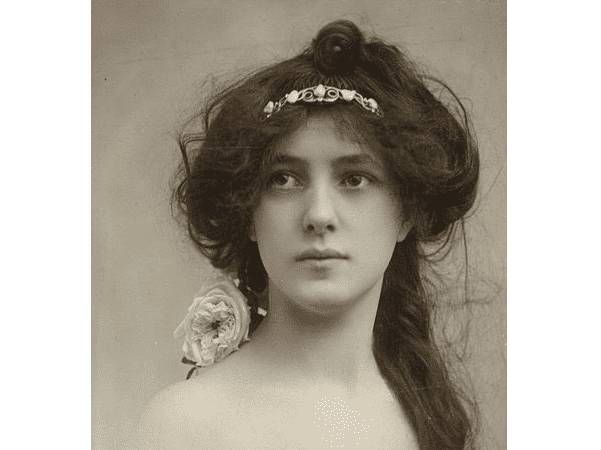

The Gibson Girl: Evelyn Nesbit

Evelyn Nesbit was the supermodel of the early 20th century, with a modeling career that started when she was a teenager. Readers of the era saw Nesbit’s familiar face on the covers of popular magazines and advertisements for everything from insurance to Coca-Cola. Her career eventually included work as a chorus girl and an actress. Memorialized by the illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, Nesbit was known as one of the very popular “Gibson Girls.”

What is a Gibson Girl? Gary W. Clark, author of Lessons From The Gibson Girl – Her Quest for Equality, Justice, and Love, explains:*

“The Gibson Girl was an iconic, though fictional, young woman of the early 20th century. Charles Dana Gibson drew her for weekly illustrations in popular magazines of the time. She was beautiful, stylish, and the model that young women around the world admired, copied, and emulated. The illustrated Gibson Girl was a composite of many models over a dozen years yet Evelyn Nesbit is the most recognized as the typical Gibson Girl.”

While she achieved a great deal of fame in her younger years, Nesbit’s life wasn’t easy. According to Clark:

“She lived a tumultuous life, riddled by tragedies, including… suicide attempts, and a failed stage career…This success-driven life at any cost left her vulnerable to many unfortunate encounters with people of questionable motives, including a jealous husband and a rich lover.”

While Nesbit was not starved for the attention of male suiters, she eventually settled for a marriage to the troubled millionaire Harry Thaw. That decision, possibly fueled by the hope for lasting financial security amongst other things, would profoundly affect her life.

The Lothario: Stanford White

Stanford White was well-known, respected, and a partner in an architectural firm that designed public buildings as well as homes for wealthy clients. His legacy can still be viewed today in the New York Palace Hotel, the Tiffany and Co. building, and the Washington Square Arch. He was also the designer of the building where he would meet his demise on 25 June 1906: Madison Square Garden II.

But Stanford White was not an innocent victim; he had a dark side. Though married, he preferred the company of a steady stream of much younger women whom he wined and dined until he got what he wanted – at which point he would move on to the next young beauty.

White kept a special apartment just for these purposes (called “White’s Den” in the below newspaper article) and was known for the underage company he kept.

Evelyn Nesbit was just one of many of those conquests. White assisted Nesbit and her mother, earning their trust, and then one day he assaulted Evelyn while she was unconscious.

The Husband: Harry Thaw

Harry Thaw of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is not as well-known as other millionaires from the Gilded Age like Rockefeller or Vanderbilt, but his family was once one of the 100 wealthiest families in the United States. Thaw’s parents were William and Mary Sibbet Copley Thaw.

The Thaw family faced their own demons, especially in the form of Harry’s mental problems and scandalous (sometimes public) behavior which his mother covered up using the family’s great wealth. He was persistent in his desire to marry Evelyn Nesbit; after four years she finally agreed, and the couple tied the knot on 4 April 1905.

Unfortunately, Thaw’s instability and obsession with White would lead him to shoot and kill his imagined rival.

The Crime: 25 June 1906

Thaw bought tickets to the play Mam’zelle Champagne at the rooftop theatre of the Madison Square Garden. White not only designed the second version of Madison Square Garden, he had an apartment there and a reserved table in the theatre, facts that Thaw would have known.

In hindsight, the play’s final song, “I Could Love a Million Girls,” probably seemed to Thaw an appropriate time to kill a man that he believed “…ruined my wife and I got him.” Thaw approached White from behind, shooting him three times in the back of his head. White never saw the attack coming.

Thaw murdered White in cold blood in front of witnesses who knew him either by name or reputation. He was detained and incarcerated in the Tombs, Manhattan’s Detention Complex, where he waited for his fate in a manner unlike any of his fellow prisoners. He dined on food from the exclusive New York restaurant Delmonico’s, wore his own clothes, and slept in a non-prison-issue bed. Though he had murdered a well-known and respected architect, he was treated in a manner that was afforded a man from one of the richest families in America.

The Trials of 1907 and 1908

So why was this the trial of (a very new) century?

Lessons From The Gibson Girl author Clark postulates:

“This case had everything. A murder during the production of a play on the roof of Madison Square Garden with socialites as witnesses. It involved the jealousy around the “it” girl [Evelyn Nesbit], a killer who was a member of one of the richest families in the United States, and a famous architect….”

The trial of the century was really the two trials of the century. Thaw’s first trial in early 1907 ended in a deadlock, so he was re-tried in 1908 and found guilty by reason of insanity. Although he was given a life sentence to the Mattewan State Hospital in New York, he eventually was released in 1915.

The Aftermath

So, what happened to those involved in this early 20th century “Trial of the Century”?

Evelyn Nesbit gave birth to her son Russell Thaw in 1910. Though she insisted that her husband was the child’s father, a result of his having conjugal visits while incarcerated, Harry Thaw always denied paternity. Nesbit eventually divorced Thaw in 1915 and went on to star in films with her son, as well as consult on a 1955 fictionalized account of her life in the Joan Collins’ movie, The Girl in The Red Velvet Swing. Unfortunately, she never regained the fame she once enjoyed. Her brush with scandal tarnished her reputation and she fell from the nation’s graces. She died in Southern California in 1967. Only 31 people attended her funeral.

After the trials and his eventual release from the State Hospital, Harry Kendall Thaw found himself the center of other controversies and crimes. He moved to Virginia where he worked as a firefighter, eventually dabbling in motion pictures, and then spent the last of his years living in Florida. When he died on 22 February 1947 he left a will that provided $10,000 to Evelyn and her son Russell.

Since he was murdered, Stanford White had no aftermath. But what happened following his death? His architectural partner Charles F. McKim died in 1909 reportedly from the accumulation of stress starting with White’s murder. Mrs. Stanford White (Bessie Springs Smith White) suffered additional hardships, including the selling of her home and possessions to pay her husband’s debts, and later the tragic death of her brother Robert Clinch Smith aboard the Titanic. Mrs. White died in 1950.

This sensational murder and trial, which once powerfully captured the public’s attention, has been largely forgotten now. Fortunately, it has been preserved in the pages of old newspapers.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

—————————-

* Clark, Gary W. Lessons From The Gibson Girl – Her Quest for Equality, Justice, and Love. 2016. page 79.