Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes about Anna Green Winslow, a young woman in Colonial Boston who became a fervent supporter of the American Revolution. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

The Diary of Anna Green Winslow: A Boston School Girl of 1771 (actually a collection of Anna’s letters edited by Alice Morse Earle and published in 1894) is a precious and charming account of a “quaint mind” living in Colonial America, as early reviews noted – but it offers so much more.

What Anna left behind was a rare, intimate glimpse into how the roles shifted for young adults preceding the American Revolution. The political values of Independence and Equality were advocated to many girls and boys, whose participation in eradicating British oppression were more than elementary.

In 1770 Anna Green Winslow (1759-1780) arrived in Boston from Cumberland, Nova Scotia. Her parents Anna Green and Joshua Winslow wanted her to be among the Boston society circles. The academic instruction provided to the upper society young ladies was coined “Dame Schools.” Essentially, it prepared these young maidens for marriage, instructing them in sewing, dancing, and writing.

Anna’s ancestors were Mayflower stock. She was a direct descendant of Mary Chilton and also John Winslow, brother of Governor Edward Winslow. Her maternal ancestor Percival Green came to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1635 with his wife Ellen.

Anna’s New England kin were not in line with her daddy’s politics and his love for the crown. He was commissary-general of the British forces in Nova Scotia.

The “finishing school” that Papa Winslow intended for Anna turned out to be a “revolutionary” transformation. Anna’s hosts, Aunt Sarah Winslow Deming and Uncle Captain John Deming, exposed her to a social climate hot with revolt.

Aunt Sarah was considered one of the prettiest belles of Boston and a friend of Mrs. Adams and other high-ranking dames. Her husband Captain Deming was the son of Samuel Deming, whose ancestors settled Wethersfield, Connecticut. Captain Deming was an ensign in the Ancient and Honorable Artillery in 1771, and a deacon of the Old South Church in 1769.

While Anna mingled and dined with top-drawer socialites, she adopted their political ideology as well. (Diary entry: “September 23 1772 I din’d at aunt Suky’s with Mr & Mrs Hooper of Marblehead.”)

However, in between her lessons and punch bowl soirees, Anna witnessed the true fervor fueling the American Revolution. On June 4 she notes an extraordinary event:

“The whole regiment muster’d upon the common. Mr Gannett, aunt & myself went up into the common, & there saw Capt Water’s, Capt Paddock’s, Capt Peirce’s, Capt Eliot’s, Capt Barret’s, Capt Gay’s, Capt May’s, Capt Borington’s & Capt Stimpson’s company’s exercise. From there, we went into King street to Col Marshal’s where we saw all of them prettily exercise & fire.”

Here is a diary entry of Anna visiting the home of Colonel Richard Gridley and Hannah Deming:

“I went a visiting yesterday to Col. Gridley’s with my aunt. After tea Miss Becky Gridley sung a minuet. Miss Polly Deming & I danced to her musick, which when perform’d was approv’d of by Mrs Gridley, Mrs Deming, Mrs Thompson, Mrs Avery, Miss Sally Hill, Miss Becky Gridley, Miss Polly Gridley & Miss Sally Winslow. Col Gridley was out o’ the room. Col brought in the talk of Whigs & Tories & taught me the difference between them.”

When the Massachusetts Provincial Congress needed someone to head the Massachusetts Train of Artillery, it appointed Gridley as its colonel on 19 May 1775. He fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill. (Baule, Stephen)

Anna’s lessons were given by the best scholars and die-hard Patriots, such as “Master Holbrook.” Earle notes in her introduction to the diary that Anna was taught by Samuel Holbrook, who was “one of the ‘Sons of Liberty’ who dined at the Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester, Massachusetts on August 14, 1769; and he was a member of Captain John Haskin’s company in 1773… and a member of the Old South Church.”

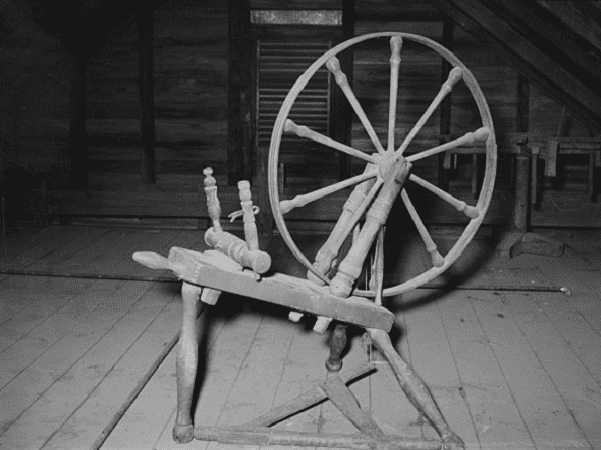

Anna, who once sported the latest London fashions, shed her Loyalist attire and joined the women warriors of the “Patriotic sewing circles.” All the rage became spinning and weaving cloth to make homegrown dress attire – boycotting all things British.

Ann Marie Kordas points out in her book The Politics of Childhood in the Cold War that American freedom was not only won by the sacrifice of select elders, but a large percentage of the youth recruited to assist in the cause. Even after the Revolution children were groomed to be patriots. The communities instilled love of country and the significance of liberty, justice, and equality – very much like the mantra of Ben Franklin that motivated the Colonies: “We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

The newly enlisted lasses, such as Anna, willingly fulfilled their duty. Her diary notes that she strove to wear only garments made by homespun cloth: “As I am (as we say) a daughter of liberty I chuse to wear as much of our own manufactory as pocible.” Anna and her “sisters of the Old South” met frequently to spin and sing songs.

She writes: “My cousin Sally reeled off a 10 knot skane of yarn today.” A few days later, on February 18: “Another ten knot skane of my yarn was reel’d off today. Aunt says it is very good.” Her cousin Sally was Sarah Winslow, daughter of Elizabeth Mason and John Winslow, brother of Joshua Winslow.

According to Phillip Hoose in We Were There, Too! Young People in U.S. History, Boston was dominated by the spirit of Liberty. The Sons of Liberty were meeting around the clock, while the Daughters of Liberty held spinning and weaving bees. By the time Anna arrived over four hundred spinning wheels had been built in Boston, and one Patriot boasted there were more looms in one town than houses.

While the girls gathered to spin their emancipation garb, they also pledged to drink no British tea till the revenue act was repealed. An association formed within the sewing circles with the proud declaration: “We, the daughters of those Patriots who have appeared for the public interest, do now with pleasure engage with them in denying ourselves the drinking of foreign tea.”

Hoose asserts that the children “felt the thrill of revolt and joined in patriotic demonstrations,” and the entire graduating class at Harvard, to encourage home manufactures, took their degrees in homespun.

With her diary, Anna Green Winslow left us a valuable gift, which we are “sew” thankful for. This crafty “Daughter of Liberty” will never go out of fashion, nor will the stories woven from “Patriotic sewing circles” run out of good material!

Charity Clark, another member of the “Patriotic sewing circles,” wrote in a letter:

“Heroines may not distinguish themselves at the head of an Army, but freedom will also be won by a fighting army of amazons… armed with spinning wheels.”

Genealogy:

Anna Green Winslow’s mother, Anna Green (1728-1816), was the daughter of Anna Pierce (1702-1770) and Joseph Green (1703-1765), a wealthy merchant. Anna Pierce was the daughter of Joshua Pierce and Elizabeth Hall of Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Joseph Green was the son of Rev. Joseph Green and Elizabeth Gerrish.

Anna Green Winslow’s father, Joshua Winslow (1726-1801), was the son of John Winslow (1693-1731) and Sarah Pierce (1697-1771).