Introduction: The current presidential campaign reminded historian Jane Hampton Cook of Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for president on a political party ticket, in 1872. Jane is a presidential historian and author of “Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists and Women’s Right to Vote.” Her works can be found at Janecook.com. She is also the host of Red, White, Blue and You

U.S. News and World Report published an article in March 2024 observing that 12 women are currently serving as state governors and 49 women have served as governors over the decades. Within the past ten years, two women have run for president of the United States, including the current vice president, on a political party ticket. As a result, modern Americans are increasingly familiar with female political leadership.

In contrast, the first election in which a woman ran for president on a political party ticket took place more than 150 years ago. A new political party that supporter women’s rights, the National Equal Rights Party, nominated Victoria Claflin Woodhull (1838-1927) to be its candidate in the 1872 presidential election – even though women could not legally vote in federal elections. (Though he was not present at the convention and did not take part in the upcoming campaign, the Party nominated civil rights activist Frederick Douglass to be its candidate for vice-president.)

The idea of a female president was such an extreme novelty in 1872 that newspaper coverage of this event led to articles filled with as much sarcasm as facts. Many of these articles aren’t fit to print today because they used racial slurs among other sexist tropes.

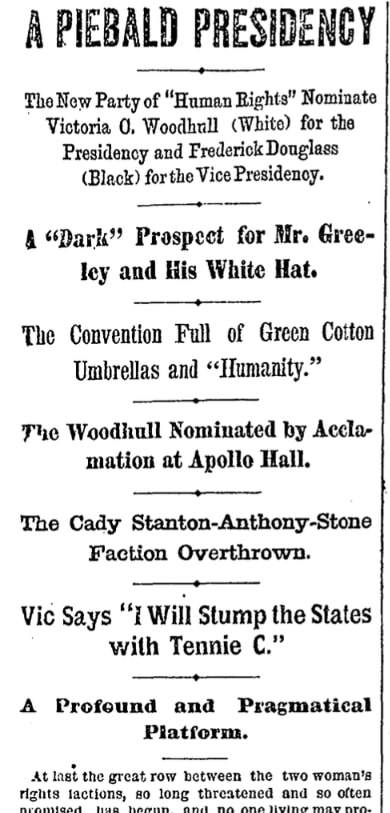

A New York Herald article avoided the worst of the contemporary smears but used tongue-in-cheek language to chronicle the National Equal Rights Party’s convention at New York’s Apollo Theater on 10 May 1872, when Woodhull was nominated.

This New York Herald article details three pieces of hard news among the colorful imagery.

The first news was a rift between two groups in the women’s rights movement, which had begun in 1848 through the Seneca Falls Convention championed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Most of these activists had put aside their calls for women’s voting rights to advocate for abolishing slavery during the Civil War. When the 14th and 15th Amendments failed to overtly include women, these activists renewed their calls for women’s right to vote, among other policies.

The article reports:

At last the great row between the two woman’s rights factions, so long threatened and so often promised, has begun, and no one living may prophesy where it will end.

For some time past a quarrel has been brewing between the moderate and conservative wings of the female shriekers, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, the impregnable; Lucretia Mott, the venerated; and Lucy Stone, the stainless on one hand; and the rebels, led by Victoria Woodhull and Tennie C. Claflin, on the other side.

The issue dividing the women into two groups was Woodhull’s advocacy for free love. After marrying as a teenager and then divorcing her husband because of his infidelity, Woodhull advocated for free love. Divorce, even for abusive marriages, was rare at this time. She believed that she had a natural right to love whomever she chose for as long or short as she wanted.

By this time, Woodhull owned a stock brokerage and published an advocacy newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. Some activists, however, believed that Woodhull’s free love position distracted from their main goal of women’s voting rights. The article reports:

On the free love question the Woodhull is bold beyond precedent, and is fearless enough to speak her mind plainly in the faces of immense audiences… It is even hinted that many of the most prominent among the dwindling Stanton-Anthony faction are secretly inclined to favor the free love doctrines, but dare not do so openly as they are unfortunately saddled with husbands, fathers and brothers who might kick at the further spread of the terrible heresy.

The second piece of hard news from the convention was the Equal Rights Party’s platform. As if playing a video, the article used colorful imagery to describe the convention’s scene before documenting their platform’s planks. The article reports:

Apollo Hall, where the radical wing of the female shriekers met yesterday, is situated at the corner of Broadway and Twenty-eighth Street, and is a large, well-ventilated and handsomely frescoed hall. About six hundred delegates (male and female) had assembled at the bidding of the Woodhull to join a new “People’s Party”…

The article describes some of the women as:

…more homely in the face than as many nutmeg graters, while here and there a beautiful and fascinating creature, with serious countenance and wavy figure encased in Dolly Varden costume, walked through the aisles, the observed of all observers.

Dolly Varden is a character from Charles Dicken’s historical fiction novel Barnaby Rudge, which takes place in 1780. Dolly Varden outfits were modern, patterned or printed dresses that resembled styles and dress shapes from the 1780s. The article further reports:

The victorious Woodhull, also attired in black silk, with an overskirt, and having at her throat a blue silk necktie, came in late in the day, with a smile on her lip, and her sister, Tennie C. Claflin, similarly attired, on her arm. Wherever these two Amazons went crowds of the delegates clustered around them, and many ladies embraced and kissed Mrs. Woodhull.

The hall boasted blue silk banners featuring Bible verses in gold letters. Red banners portrayed political statements, such as “Government protection and provision from the cradle to the grave.”

Then the New York Herald article reveals the second piece of hard news: the platform of the new Equal Rights Party. The first of the 23 planks was the boldest:

“That there should be a complete reconstruction of several of the most important functions of the government of the United States, and to that end we advocate the adoption of a new Constitution which shall be in perfect harmony with the present wants, interests and condition of the people.”

The twentieth “Declaration of Principles” stated:

“That there should be perfect and free expression of opinion by vote on all political subjects by all citizens of all classes, sexes and conditions being of competent age.”

Among the other planks were positions supporting the abolishment of monopolies, a direct tax, and public laws regulating labor.

The third piece of hard news from the convention was the nomination of Victoria Woodhull to be the party’s presidential candidate.

Titling her speech “Political, Social, Industrial and Educational Equity,” Woodhull addressed the enthusiastic audience. Here are some of her remarks:

“From this convention will go forth a tide of revolution that shall sweep over the whole world. Let us be careful, then, that its fountain contains no subtle poison of selfishness or of expediency, which shall distill death. But what does freedom mean as applied to individuality? Why, just this (it was never more forcibly, clearly or logically set forth than in the Declaration of Independence), the inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

The article reports the audience’s reaction to Woodhull’s nomination:

The audience again rose and cheered as if their lungs would break, when an alarming rumor ran around the room that Mrs. Woodhull had fainted on the platform from excess of emotion, but when Mrs. Woodhull was led forward by the chairman to respond, the applause was again and again renewed. Flushed and heated with gratified pride, her bosom heaving and her voice trembling, she said: “I thank you from the bottom of my soul for the honor you have conferred upon me tonight.”

And with those words, Victoria Woodhull became the first female nominated for president of the United States by a political party. Her running mate was also a historic first.

Though some knew that civil rights activist Frederick Douglass was committed to re-electing Republican President Ulysses Grant, the convention nominated Douglass anyway as Woodhull’s vice president. Douglass was not present at the convention and did not acknowledge his nomination.

This unprecedented combination of a white woman and a black man nominated to run for president and vice president by a political party, led to the New York Herald’s headline: “A Piebald Presidency.” (Piebald is a term used to describe a horse or other animal that features patches of colors, usually black and white, on its coat.)

The 1872 presidential election was primarily between incumbent Republican President Ulysses Grant and newspaper publisher Horace Greely, who was nominated by both the Liberal Republican Party and the Democratic Party. Earning no Electoral College votes, the Equal Rights Party was one of a few minor parties, which included the Labor Reform Party and the Straight-Out Democratic Party.

Victoria Woodhull, however, was in jail on election day in 1872. She’d been accused of publishing obscene information when she exposed an adulterous affair by a prominent New York minister, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, in her newspaper. In addition to the novelty of her nomination, Woodhull had another obstacle to becoming president: she was too young, not yet 35 years-old at the time of the 1872 election as required by the Constitution.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: cabinet card portrait photograph of Victoria C. Woodhull, c. 1870. Credit: Nate D. Sanders; Wikimedia Commons.