The Famous “Shot Speech”

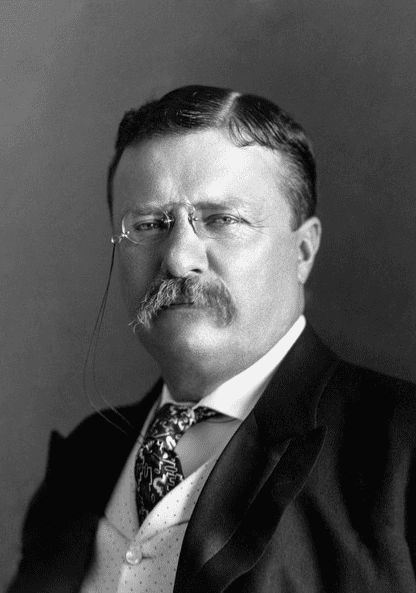

It almost seemed like a political advertising campaign gone awry – but one no consultant would ever dare propose. When Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt formed the Progressive Party to run for a third term as president in 1912, it became known as the “Bull Moose Party” after he declared: “I’m as fit as a bull moose.” Then, thanks to a would-be assassin’s bullet, Roosevelt got the chance to back up that claim. The Roosevelt assassination attempt showed America just how tough and persistent this former president was.

Just before 8:00 the evening of 14 October 1912, as Roosevelt was entering a car on his way to deliver a speech at a campaign rally in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a mentally-unstable assailant named John Schrank fired a .38-caliber bullet point-blank into the ex-president’s chest.

Roosevelt waved off his doctor and insisted on being driven to the rally and delivering his prepared remarks. With the bullet lodged in his chest and blood slowly seeping into his shirt, Roosevelt began his speech by telling the crowd: “I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a bull moose.”

What happened next was grand theater, as described in the reporter’s eye-witness account reprinted below. For over an hour Roosevelt delivered his speech, driving the crowd of 15,000 into paroxysms of anxiety whenever he occasionally winced in pain, paused for a drink of water, or seemed to falter as his voice grew weaker. But each time, the Spanish-American War veteran and renowned big-game hunter rallied his legendary strength, calmed the worried crowd, and continued. When he finished the speech, the crowd roared with a response the reporter said was “deafening.” And little wonder!

Only after he delivered his speech and strode off the stage did Roosevelt allow doctors to examine him. They found that the bullet, after going through his thick overcoat, the folded 50 pages of his prepared speech tucked into his breast pocket, and the metal spectacle case in that same pocket, still had enough force to burrow three inches into his chest, stopping just short of damaging his lung and causing a potentially fatal injury.

It was not the overcoat, thick manuscript, or eyeglass case that saved Roosevelt, however – it was his own physique.

Theodore Roosevelt had been born a weak, sickly boy. Showing at an early age the fearless determination that would fuel his energetic life, he adopted a rigorous, daily program of strenuous exercise that gave him a powerful physique.

What stopped that bullet, and saved his life, were the thick slabs of muscle in his massive chest. What gave him the strength to stand for more than an hour, delivering a speech moments after being shot, was his legendary endurance. He was, indeed, strong as a bull moose.

Ultimately, the doctors decided it was too dangerous to remove the bullet, and Roosevelt carried it inside his body for the rest of his life. He defeated the Republican candidate, incumbent President William Howard Taft, in that 1912 election – but lost to the Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson. He may have lost the election, but his astonishing performance that Oct. 14 night added another illustrious chapter to a career that included leading his men, the “Rough Riders,” on the charge up San Juan Hill; taking on big trusts during his presidency, and staring down bull elephants on his African safari.

A reporter, John B. Pratt, was following Roosevelt during that 1912 presidential campaign and was there when Teddy Roosevelt was shot. He wrote the following, vivid account of the shooting and the infamous Teddy Roosevelt shot speech.

Here is a transcription of this article documenting the entire assassination attempt on Roosevelt from start to finish.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Colonel Roosevelt Shot and Seriously Wounded by Crank;

Quiet Ordered; Permitted to See No One

J. W. Schrank, a New Yorker, His Assailant

Made Attack as Teddy Was Leaving His Hotel in Auto

Early Reports Represented His Injury as Slight

Insisted upon Making His Speech in Milwaukee

Chicago, Oct. 15. – An attempt to assassinate Col. Theodore Roosevelt, Progressive candidate for president, was made early last evening in Milwaukee, when John W. Schrank, believed to be a crank, shot the colonel in the right breast.

The bullet, a .38 caliber, entered an inch below the right nipple and ranged upward and inward about four inches.

Colonel Roosevelt’s is not a mere flesh wound, but is a serious wound in the chest, said a bulletin issued this afternoon by physicians at Mercy hospital, where he was brought this morning.

Disquieting Bulletins Issued by Surgeons

At 1:05 p.m. the following bulletin was issued:

“The examination of Colonel Roosevelt at 1 p.m. showed that his temperature was 98.8; his pulse 92; his respiration normal. It pains him to breathe. He must have absolute quiet; must cease from talking, and not see anyone until we give permission.

“This is not a mere flesh wound, but is a serious wound in the chest and quietude is essential.”

(Signed)

J. B. Murphy

Arthur Dean Bevan

S. L. Terrell

By John B. Pratt

Milwaukee, Oct. 15. – An attempt to assassinate Colonel Roosevelt was made as he started on his way from the Hotel Gilpatrick in this city to the Auditorium, just before 8 o’clock last evening.

As he stepped into an automobile a shot was fired by a roughly attired man, John W. Schrank of New York City, who edged his way through the crowd to the motor car. Schrank took deliberate aim and sent the bullet crashing into the ex-president’s right side an inch below the nipple.

The shooter was nabbed by Elbert E. Martin, the ex-president’s stenographer, and Capt. Alfred O. Gerard of Milwaukee, a Rough Rider under Roosevelt.

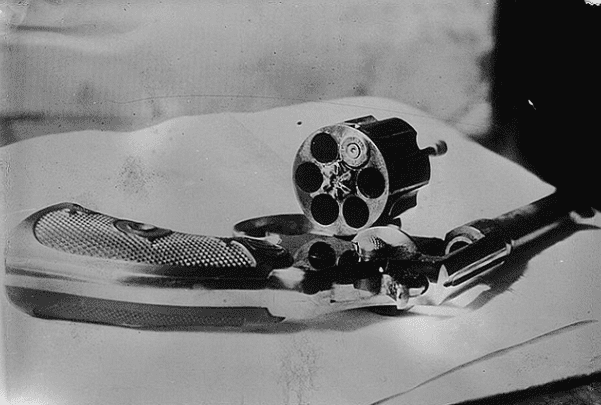

As he was about to fire another shot, the revolver, a .38-caliber affair, was knocked from his hand by Martin, while Col. Cecil Lyon of Texas, who is accompanying Roosevelt on his Midwestern campaign trip, started to choke the would-be assassin.

Roosevelt staggered back into the auto when the shot was fired, but raised himself up and stood looking at Lyon, who was sitting on Schrank. The ex-president cried with a gesture:

“Don’t hit him. I’m all right.”

A captain of police rushed in as Lyon released his grip on the fellow and with Lyon’s help dragged the man into the hotel kitchen.

“I’m Not Hurt; Good Luck”

Colonel Roosevelt sat back in the motor car as an immense crowd that had witnessed the shooting yelled to him.

With rare presence of mind the colonel, waving his hat, cried out: “My good friends, I’m not hurt, I’m going on to the hall to speak. Good luck.”

The whole incident had occurred so quickly that the astonished crowd did nothing but stand stock still.

Roosevelt even turned to the chauffeur and in a calm voice remarked:

“Now, just run the car up to the Auditorium. I’m not hurt and everything’s all right.”

The car started up and in a moment Roosevelt was on his way to the hall with a bullet in his side.

The ex-president did not realize that he had been shot until he got to the Auditorium, five blocks distant. He knew that the bullet had grazed him, because he felt it against his side, but he believed that it had simply gone through his overcoat.

As he reached the Auditorium he instinctively placed his hand upon his wound. Dr. Terrell, his private physician who rode in the automobile with him, noticed the gesture.

“Colonel, I believe you are hurt,” he suggested with alarm.

“No, not at all,” returned Roosevelt with a smile. “I feel fine.”

“I want to see if the bullet hit you,” insisted Terrell.

“Don’t bother yourself,” said Roosevelt. “You’ll delay the meeting and there are people waiting in the Auditorium to see me.”

This colloquy took place in a room just outside the Auditorium.

Fifteen thousand people in the hall had heard the ex-president’s automobile whirring up to the Auditorium.

Dr. Terrell was obdurate.

“You can’t go in there until I’ve seen if that bullet took effect,” demanded Terrell.

In the meantime members of the ex-president’s party, in great alarm, had gone to the platform of the Auditorium to prepare the huge audience for the shocking news of the attempted assassination.

Audience Shocked by the News

Henry Cochems of Wisconsin, former La Follette leader who is now working for the colonel, stepped up to the chairman of the assemblage and instructed him to whisper the news.

“My God!” exclaimed the startled man, and he sank back into a chair. The audience looked on in blank amazement. Cochems stepped to the front of the stage and in quavering voice announced:

“Ladies and gentlemen, I have sad news for you. Colonel Roosevelt has been shot.”

A murmur ran through the audience.

“Some crank shot at him as he was on his way here,” Cochems went on. “The colonel is outside here and will soon address you because he insists on it. I ask you to be as quiet as you can, as he is in great pain.”

Cochem’s voice failed as he uttered this and he staggered back against a table. He was completely unnerved. As Cochems was helped away from the platform the crowd broke into a murmur of excited babble. Cochems regained his composure as he was being led from the platform and, going to the footlights, called out:

“Are there any physicians present? They are needed.”

Colonel Persists in Making Speech

Instantly Dr. R. G. Sayle and Dr. Frank G. Stratton of Milwaukee hurried back. Dr. Terrell was sitting on a chair before Colonel Roosevelt. He was trying to induce the ex-president to give up a speech and go home.

“But, doctor, that is impossible,” declared Roosevelt firmly. “I’m going to make a speech if it’s the last one.”

Drs. Stratton and Sayle nodded to the ex-president and asked him if he felt any pain. Roosevelt, who was sitting up straight in a chair, the most placid man in the group, replied with a wave of his hand:

“No, I am not hurt a bit. I don’t think the bullet hit me. If you’ll wait until I’ve finished my speech I’ll let you see for yourselves.”

As he spoke, Roosevelt got up from the chair and insisted on being shown the way to the stage. Dr. Terrell implored him not to go. Colonel Lyon tried to stop him, but Roosevelt gently pushed the Texan aside, saying:

“Now, Cecil, you’re disturbing the campaign.”

Gets Wildest Cheer of Campaign

Seeing it was useless to interfere, the colonel’s bodyguard escorted him to the platform. As Roosevelt walked firmly to the stage as though nothing in the world was the matter, the gigantic crowd burst into the wildest cheer he has heard in his campaign trip. Roosevelt, who had clung to his hat through all the excitement, passed it over to his cousin, Philip Roosevelt, and faced the yelling throng. He waved his hand at the crowd, paced a few steps along the platform, waved at the galleries and acted exactly as he did at the Coliseum at Chicago last Saturday, when he was the storm center of a wild multitude.

Roosevelt finally raised his hand to stop the cheering and as the crowd ceased, a voice cried:

“Colonel, we sympathize with you.”

Roosevelt gritted his teeth and shouted back:

“Now, don’t you worry; it’s nothing at all.”

The ex-president had in his pocket a carefully prepared speech which he had dictated on the train on his way to Milwaukee. Without any formality, excepting to greet the crowd as “fellow citizens of Wisconsin,” the colonel pulled the manuscript of his speech from his pocket. As he drew it out, he found for the first time that the bullet had penetrated his body.

Bullet Pierces His Manuscript

The bullet had torn a round hole in the thick manuscript. It had gone on into the fleshy part of the chest and had lodged there.

Those who were near saw a tinge of red on the manuscript. Dr. Terrell, bound on having his way, started from his chair. Roosevelt started impatiently:

“You just stay where you are,” he said. “I am going to make this speech and you might as well compose yourself.”

The doctor, balked by the colonel, returned to his chair, his face blanched as Roosevelt launched into his speech. The audience, seriously alarmed over the colonel’s plight, sat with bated breath as Roosevelt spoke.

Roosevelt gave not the slightest indication that he felt the effect of his wound. Once, however, a sudden twinge of pain made him clutch his right side. The audience was quick to observe it and a protest ran through the hall for the colonel to stop.

Roosevelt frowned. “No, this is all a trivial affair,” he said. “Anyone who knows me must realize that I would not stop for a thing like this. I may have a right to feel sore with a bullet in me. But if you saw me in battle, leading my regiment, you would not want me to stop. You would expect me to go ahead, no matter what happened.”

On into his speech went the colonel. His voice rose to a high pitch. To hear him speak with all the vigor he has displayed in his whole campaign, no one would have imagined, had he not known it, that the plucky candidate carried a freshly fired bullet.

After Roosevelt had talked for half an hour, he ceased for a minute to take a glass of water. This was taken by the crowd to indicate that he was growing faint. In intense perturbation, a woman in the audience arose and cried:

“Colonel Roosevelt, won’t you please let doctors look for that bullet? We can wait till they’re through. We’re afraid you are seriously hit.”

Roosevelt gently laid down the glass of water. Leaning over the platform, he exclaimed in soft, even tones: “Madame, I am not seriously hurt.”

Deafening Cheers Greet Conclusion

The ex-president went on with his speech for half an hour longer. He curtailed his address only a trifle. When he reached its conclusion, Roosevelt smiled amiably and with a comprehensive gesture said indulgently:

“Now, my friends, I want to thank you for your forbearance. You have listened patiently to me. Thank you and good luck.”

A deafening round of cheers went up as the ex-president was escorted from the stage.

The doctors advised him that they were already prepared with means to make an immediate examination of the wound at the Emergency hospital.

“Oh, do it here,” urged the colonel, as he started to sit in a chair. The doctors insisted that he ought to go to the hospital.

“If you think it’s that bad, I’ll go,” said Roosevelt, cheerfully.

The ex-president felt his coat and found that the bullet had scorched it on its way through. Underneath his vest was crimsoned.

“Do you feel much pain?” asked Dr. Terrell as he helped the colonel into the automobile.

“Nothing to speak of,” replied Roosevelt with a show of nonchalance. “The bullet undoubtedly is embedded in the flesh. The lung shows no injury.”

While the colonel was on his way to the hospital, which is ten blocks from the Auditorium, a message was sent to Mrs. Roosevelt at Oyster Bay, telling her of the shooting. She was informed that the wound was slight and that the colonel had gone ahead with his speech, suffering from no discomfiture. Other messages were hurried out to various others of the colonel’s family, including Nicholas Longworth.

Schrank’s Efforts to See Colonel

Schrank had been in the crowd in the street when Roosevelt drove up in an automobile at the Gilpatrick at dusk.

He waited while Roosevelt was at dinner. Poorly dressed, about 35 years old, of wiry build and long hair, he asked the clerk at the desk where he could find the ex-president.

“He’s at dinner and you can’t see him,” returned the clerk, curtly, as he critically surveyed the caller.

“Well, I’ve got to see him,” mumbled Schrank. “I’ve got to see him.”

The clerk bluntly ordered the unwelcome visitor from the hotel and he shuffled out. He evidently waited around the street in a throng that hung around to see the colonel as he left for the Auditorium.

It was shortly before 8 o’clock when the ex-president walked out of the hotel and stepped into a touring car. He had just got into the tonneau and turned around to sit down when from the opposite side of the car, facing the street, came a flash and a loud report.

Martin and Lyon Seize Would-Be Assassin

Leaning over the car was the ill-visaged Schrank who had shuffled, an hour before, into the hotel looking for the colonel. In his hand was a revolver. After firing the first shot the would-be assassin leveled the weapon again at Roosevelt and was about to fire again when Martin, the ex-president’s stenographer, a strapping fellow, leaped at him.

Martin knocked the revolver from the fellow’s hand. Colonel Lyon jumped from the automobile and gripped his hands about the neck of the man whom Martin had felled. Lyon choked the shooter and was for finishing him on the spot.

Colonel Roosevelt had fallen back against the cushioned seat of the automobile when the shot struck him. Jumping up, he called out to Lyon:

“Don’t hurt him; let me talk to him.”

Martin and Captain Gerard, the Rough Rider, hustled the shooter through the excited crowd, who were for lynching him.

A menacing crowd, bent on stringing the fellow up to a telegraph pole, trailed along into the hotel. The police drove them back. The stranger was taken into the hotel kitchen and later rushed off to police headquarters.

At the Emergency hospital, the physicians said:

“Colonel Roosevelt has a superficial flesh wound in the right breast, with no evidence of injury to the lung. The bullet is probably lodged somewhere in the chest wall, because there is but one wound, and so sign of injury to the lung.

“The bleeding was insignificant, and the wound was immediately cleansed externally and dressed with sterile gauze by Dr. R. G. Sayle of Milwaukee, consulting surgeon of the Emergency hospital.

“As the bullet passed through Colonel Roosevelt’s overcoat, other clothes, doubled manuscript and metal spectacle case, its force was diminished. The appearance gives evidence of a much spent bullet. His condition was so good that the surgeons did not object to his continuing his journey in his private car to Chicago, where he will be placed under surgical care.”

Dr. S. L. Terrell.

Dr. R. G. Sayle.

Dr. Colt Bloodgood,

Of the faculty of John Hopkins University.

Dr. T. A. Stratton.

The Teddy Roosevelt assassination attempt will never be forgotten in presidential election history. His bravery and perseverance was reflected not only through this unfortunate experience, but also through his two terms in office as the President of the United States.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Article: