Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry searches old newspapers to learn details about the life of – and funeral service for – American Revolutionary War hero Brigadier General Enoch Poor. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

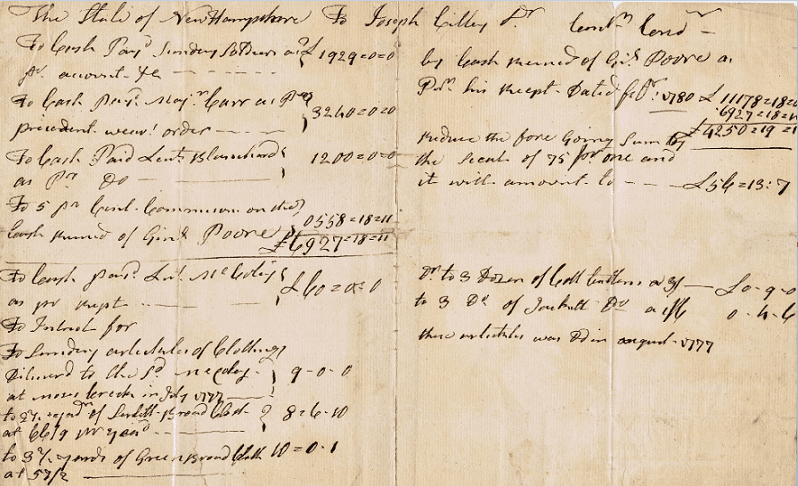

Author’s Note: The Heritage Collectors Society sent me a document to research: “The State of New Hampshire to Joseph Cilley,” from 1777. This document records payments made to sundry officers and soldiers from the American Revolution. The items for Major James Carr, Lt. Blanchard, and General Enoch Poor are included. I discovered that Captain Joseph Cilley and Brigadier General Enoch Poor/Poore were not only serving together during the American Revolutionary War, but share the same blood lines and their children married. (The family lines are listed at the end of this article.) GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives were one of my best resources for gathering information on General Poor. The tidbits on his life and funeral service were the best!

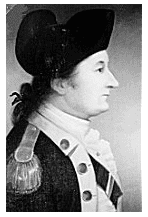

The military record of Brigadier General Enoch Poor (1736-1780) is extensive and very impressive. Enoch was born in Andover, Massachusetts, on 21 June 1736 to Thomas Poor and Mary Adams. He served as a private in the French and Indian War with his brother Thomas, who was a captain.

After he returned from the French and Indian War, Enoch began a trade as cabinetmaker and by 1761 was ready for marriage – and a lass of his native town was chosen.

According to an article published in the Arkansas Gazette, when Enoch set his sights on colonial belle and beauty Martha Osgood, he was not approved by daddy Osgood. But Enoch was too smitten to walk away. Apparently, daddy Osgood resorted to stringent tactics and locked Martha away in her bed chamber. Martha camped out at the window waiting for Enoch.

Charlotte Helen Abbott, in Early Records of Andover, noted that with the aid of a slave named Brewster, Enoch carried Martha down a ladder from her parents’ home and they eloped. Enoch and Martha moved to Exeter, New Hampshire, and eventually daddy Osgood made peace with his son-in-law.

Enoch learned the cabinetmaker trade and was quite skilled, as shown by this beautiful Secretary he made.

Enoch then evolved his craft into a prosperous shipbuilding business. According to an article published in the New Hampshire Patriot and Gazette, Poor employed many men in shipbuilding, and during the summer of 1775 their skill was utilized for building fire rafts at Exeter, New Hampshire, in case British ships attempted to burn Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Enoch served in the Continental Army from 1775-1780 during the Revolutionary War, and was promoted to brigadier general on 21 February 1777. He led troops in many engagements, including the Battles of Saratoga, Freeman’s Farm, Bemis Heights, Monmouth, and Newtown.

Washington, Lafayette and a portion of the American army attended the burial of General Poor in 1780.

Poor’s funeral is described in the Military Journals of James Thatcher, who was a surgeon in the Continental Army:

“He [General Poor] was a true patriot, who took an early part in the cause of his country, and during his military career was respected for his talents and his bravery, and beloved for the amiable qualities of his heart. But it is sufficient eulogy to say, that he enjoyed the confidence and esteem of Washington.”

Thatcher provided these details:

“The procession: a regiment of light-infantry, in uniform, with arms reversed; four field-pieces; Major Lee’s regiment of light-horse; General Hand and his brigade; the major on horseback; two chaplains; the horse of the deceased, with his boots and spurs suspended from the saddle, led by a servant; the corpse borne by four sergeants, and the pall supported by six general officers. The coffin was of mahogany, and a pair of pistols and two swords, crossing each other and tied with black crape, were placed on top. The corpse was followed by the officers of the New Hampshire brigade; the officers of the brigade of light-infantry, which the deceased had lately commanded.

“Other officers fell in promiscuously, and were followed by his Excellency General Washington, and other general officers. Having arrived at the burying-yard, the troops opened to the right and left, resting on their arms reversed, and the procession passed to the grave, where a short eulogy was delivered by the Rev. Mr. Evans. A band of music, with a number of drums and fifes, played a funeral dirge, the drums were muffled with black crape, and the officers in the procession wore crape round the left arm. The regiment of light-infantry were in handsome uniform, and wore in their caps a long feather of black and red. The elegant regiment of horse, commanded by Major Lee, being in complete uniform and well disciplined, exhibited a martial and noble appearance.

“No scene can exceed in grandeur and solemnity a military funeral. The weapons of war reversed, and embellished with the badges of mourning, the slow and regular step of the procession, the mournful sound of the unbraced drum and deep-toned instruments, playing the melancholy dirge, the majestic mien and solemn march of the war-horse, all conspire to impress the mind with emotions which no language can describe, and which nothing but the reality can paint to the liveliest imagination.”

In 1824 Lafayette revisited Enoch Poor’s grave, and turning away much affected, exclaimed: “Ah! That was one of my generals.”

A statue and monument to Brigadier General Enoch Poor was erected near his gravesite in Hackensack, New Jersey.

Further Reading and Sources:

- “The 1683 Jackman Willett House: A history of the families who lived here and of the current owner, The Sons & Daughters of the First Settlers of Newbury, MA.”

- GenealogyBank: “Death of the Oldest State Senator Joseph Cilley.” Boston Journal (Boston, Massachusetts), 17 September 1887, page 4; Cilley History War of 1812 and American Revolution, “The Municipal Center’s Historic Neighborhood,” John Clagett Proctor Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 18 April 1943, page 30; “General Poor: Biographical Portfolio,” Flag of Our Union (Boston, Massachusetts), 24 February 1866, page 11.

- Brown, Patten Gilbert. “Joseph Cilley: Soldier and Citizen Made a Mason under Marching Order,” The Granite Monthly: A New Hampshire Magazine Devoted to History, Biography, Literature, and State Progress, Volume 42.

- Scales, John. Life of Gen. Joseph Cilley, Standard Book Company, Manchester, New Hampshire, 1921.

- Akerman, Amos Tappen. “Sketch of the Military Career of Enoch Poor, Brig. Gen. in the Revolutionary War,” 1878.

- Baker, Henry. “Oration upon the Unveiling of the Statue of General Enoch Poor by Henry M. Baker,” American Monthly Magazine, 1906, page 57.

- The Sons and Daughters of the First Settlers of Newbury Website

- Seacoast Online: Barbara Rimkunas, “The life and times of Brigadier General Enoch Poor.”

- Heitman, Francis Bernard. “Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783.”

Genealogy:

- Brigadier General Enoch Poor/Poore (1736-1780), born in Andover, Massachusetts, to Thomas Poor/Poore (1704-1779) and Mary Adams (1707-1789), married Martha Osgood (1747-1830), daughter of Colonel John Osgood (1712-1775) and Martha Carleton (1722-1755).

- Mary Adams, daughter of Captain Abraham Adams and Ann Longfellow, daughter of William Longfellow and Anne Sewall Short, widow of Henry Short.

- James Blanchard (1749-1799), son of James Blanchard and Rebecca Hubbard, married Margaret De Peyster (1749-1796).

- Captain Joseph Cilley (1734-1799), son of Captain Joseph Cilley (1701-1786) and Elise Rawlins (1701-1801), daughter of Benjamin Rawlins.

- Joseph’s father moved from Newbury, Massachusetts, to Nottingham, New Hampshire, in 1727. “June 15, 1775. On motion of Doctor Hall Jackson, Major Joseph Cilley was made a Mason gratis ‘for his good service in defense of his country.’”

Children of Enoch Poor and Martha Osgood:

- Martha Poor (1760-1834), married Bradbury Cilley (1760-1831), son of Captain Joseph Cilley (1734-1799) and Sarah Longfellow (1739-1811).

- Mary Poor (1769-1848), married Jacob Cram (1762-1833), son of Colonel Jacob Cram (1737-1806) and Sarah Putnam (1736-1783).

- Harriet Poor (1780-1838), married Major Jacob Cilley (1773-1831), son of Captain Joseph Cilley (1734-1799) and Sarah Longfellow (1739-1811).

Children of Capt. Joseph Cilley and Elise Rawlins:

- Anna Cilley (1726-1816), married John Mills.

- Mary “Polly” Cilley (1730-1813), married Richard Sinkler/Sinclair (1731-1813).

- Cutting Cilley (1738-1825), married Martha Morrill (1729-1787).

- Alice Cilley (c. 1748-1847), married Enoch Page (1742-1831).

- Joseph Cilley (1734-1779), married Sarah Longfellow (1739-1811), daughter of Judge Jonathan Longfellow and Mercy Clark. According to The American Monthly Magazine, Vol. 38, Mercy was a most excellent Colonial Dame descended from honorable lines. Judge Jonathan was the son of Nathan Longfellow and Mary Green, grandson of Ensign William Longfellow and Ann Sewall, sister of Judge Samuel Sewall, and married Henry Short of Newbury (p. 250, 1911).

Children of Joseph Cilley and Sarah Longfellow:

- Sarah Cilley (1757-1833), married Thomas Bartlett (1745-1805), son of Israel Bartlett and Lovy Alice Hall. He is the nephew of Josiah Bartlett, signer of the Declaration of Independence.

- Bradbury Cilley (1760-1831), married Martha Poor (1760-1834), daughter of Captain Enoch Poor and Martha Osgood.

- Joseph Cilley (1762-1807), married Dorcas Butler (1762-1807), daughter of Rev. Benjamin Butler and Dorcas Abbott.

- Major Greenleaf Cilley (1767-1800), married Jennie Nealley (1772-1866), daughter of Joseph Neally and Susanna Bowdoin.

- Daniel Cilley (1769-1842), married Hannah Plummer/Plumer (1770-1850), daughter of Samuel Plummer/Plumer and Mary Dole (“Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution,” p. 16, 1924.

- Elizabeth Cilley (1771-1831), married Samuel Plummer/Plumer (1760-1850), son of Samuel Plummer/Plumer and Mary Dole (“Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution,” 86-87, 1912 & p. 12, 1922.

- Major Jacob Cilley (1773-1831), married Harriet Poor (1780-1838), daughter of Captain Enoch Poor and Martha Osgood.

- Anna Cilley (1775-1810), married Nathaniel Williams (1775-1804), son of John Pingrey Williams, a successful merchant of Nottingham (History of Nottingham, Deerfield, and Northwood. “History of Nottingham, MH: Comprised within the Original Limits of Nottingham, Rockingham County, N.H., with Records of the Centennial Proceedings at Northwood, and Genealogical Sketches,” p. 191-195, Cogswell, Elliot Colby).

- Horatio Gates Cilley (1777-1837), married Sally Jenness (1782-1865), daughter of Thomas Jenness and Sally Yeaton (“Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution,” p. 329, 1933.