Introduction: In this article, James Pylant tries to solve the mystery of Rhonda Belle Martin, a seemingly normal Alabama wife and mother with a secret. James is an editor at GenealogyMagazine.com and author for JacobusBooks.com, is an award-winning historical true-crime writer, and authorized celebrity biographer.

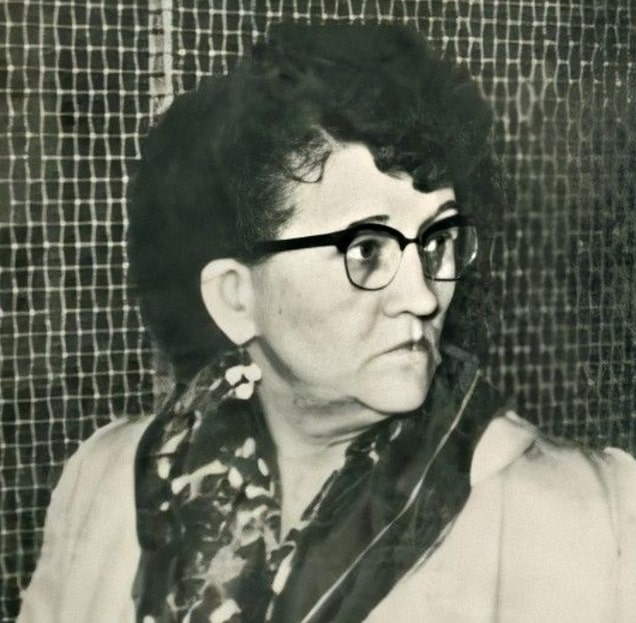

Stocky, auburn-haired, with blue eyes framed by black-rimmed glasses, Alabama waitress Rhonda Martin (1906-1957) admitted to never spending much money on her appearance. She enjoyed smoking, drinking, and reading romance magazines. Rhonda had been arrested twice, once for drunkenness and another time for reckless driving.

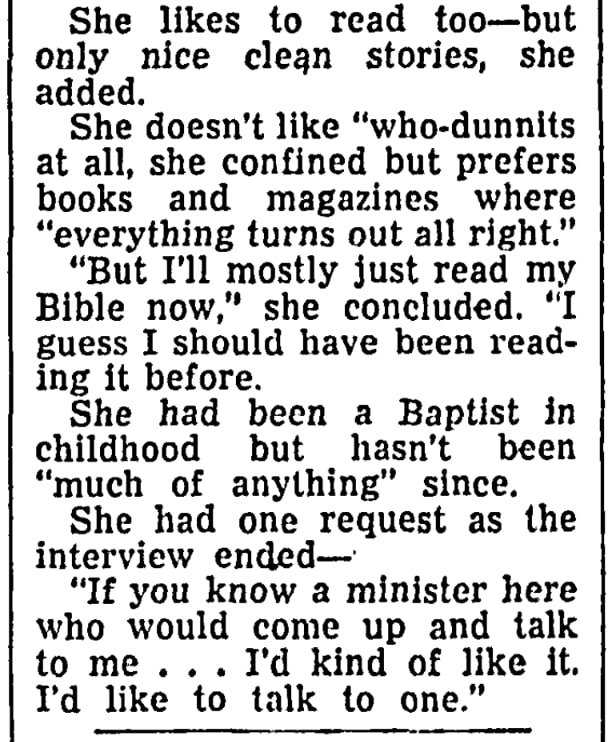

“I would always try to be a good Christian,” she said, reflecting on her life in 1956. “I’ve spent a fortune for medicine,” she added. Strangely, her family members were prone to painful illnesses. She showered them with loving attention, yet they would never recover. “I have had tragedy, always.” (1)

Rhonda’s Background

I found many details of Rhonda’s life from articles in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives.

She was born Rhonda Belle Thomley on 4 November 1906, in Lucedale, Mississippi, a logging and farming community. The Thomleys moved to Mobile, Alabama, and her father supported his wife and four children as a railroad yard laborer. She was raised in Mobile and attended a Baptist church.

Her childhood was what she called “normal,” though another time, she claimed home life didn’t offer much happiness. “I was 11 when my mother and father separated the last time,” she said.

Rhonda quit school after the seventh grade, and her father moved away, remarried, and started another family. Her mother would eventually remarry, too. At her mother’s boardinghouse, a lodger named Willie Alderman flirted with Rhonda across the dining table and asked her for a date. (2) At 15, she eloped with him to Mississippi – much to the disapproval of her mother, as reported in the Commercial Appeal.

In addition to the information you’d expect to find in a newspaper wedding notice, this one adds this unusual detail:

The couple came here [to Mississippi, from Alabama] to escape the bride’s mother, who went in pursuit of the pair, but stopped at Wilmar after learning the young folks were married.

Rhonda, at 19, divorced her husband after four years of marriage. (3) She remarried on 2 May 1928, to next-door neighbor George W. Garrett, a railroad switchman. The Garretts rented a home in Montgomery and earned extra income by taking in roomers. Over seven years, the couple had five daughters: Mary Adalaide, Ellyn, Carolyn, Emogene, and Judith.

Puzzling Series of Deaths

Firstborn Mary Adalaide died of bronchopneumonia on 15 January 1934. Emogene, at two-and-a-half, accidentally swallowed a fatal dose of poison while playing on 9 July 1937. The following year, Rhonda gave birth to Judith, who was severely jaundiced. At age eight months, the baby was hospitalized on 24 August and died two days later with lenticular degeneration, an inherited disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver.

In the early hours of Christmas morning, 1939, Rhonda’s 35-year-old husband, George, died in a Montgomery hospital. Bronchopneumonia, the same sickness that claimed Mary Adalaide, had followed a cold. And that inflammatory infection would be blamed for six-year-old Carolyn’s death five months later in May 1940.

Daughter Ellyn died three years later at age 11 in August 1943. The girl’s death certificate cited a gastrointestinal disorder and gave no indication of her sickness’s duration – only that an attending physician treated her the same day she died. Six months later, Mary Gibbon, Rhonda’s mother, was admitted into a Mobile hospital on 11 February 1944, and died that night of acute diarrhea. She was 57.

Rhonda met Talmadge J. Gipson – a customer at a café where she waitressed – and told him about her lonely widowed life. (4) She and Gipson, a gravel pit pump operator, wed on 11 August 1947, only to divorce (allegedly) two years later. Days later, the ex-Mrs. Gipson made a fourth altar run with Claude Martin, her coworker at a glass factory, in October 1948. Rhonda would later say she left Gipson five months after their wedding; however, she never divorced him, according to author Alan G. Gauthreaux.

Claude Martin, who had been a widower, had three teenage daughters and an older son who was in the U.S. Navy. The Martins enjoyed 16 happy months together until Claude became bedridden with what Rhonda described to neighbors as a “nervous disorder.” The ever-doting wife tended to Claude constantly, feeding him and dispensing medicine. As Claude’s condition grew worse, the Red Cross arranged for his son, Ronald, to take leave from the navy for a visit. (5) Claude Martin, at 48, died on 27 April 1951, after a six-week illness diagnosed as polyneuritis. No autopsy was performed.

Seven months later, on 7 December 1951, 45-year-old Rhonda became Mrs. Martin for a second time when she married her late husband’s 24-year-old son, Ronald. His sisters opposed her stepmother becoming their sister-in-law and left home. (6)

Alabama law forbade marriage to a stepparent. “I didn’t know there was anything wrong with that,” Rhonda said. (7) Still, she didn’t consider herself Ronald’s wife; she used a secret mailing address to collect Social Security as Mrs. Claude Martin. (8) Besides, she didn’t plan to be Mrs. Ronald Martin for very long.

To be continued…

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: “Investigating a Mystery.” Designed by Freepik (www.freepik.com)

__________________________

(1) Joe Azbell, “Jailed Waitress Vows Innocence in Mate’s Death,” Montgomery Advertiser, 11 March 1956, pp. 1-A, 5-A.

(2) Ibid., p. 5-A.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Jonas Bayer, “Redhead Hellcat,” True Detective, Vol. 65 (June 1976), no. 2, p. 30.

(6) Ibid., pp. 30-31.

(7) Azbell, “Jailed Waitress Vows Innocence in Mates’ Death,” p. 5-A.

(8) Bayer, “Redhead Hellcat,” p. 88.