At dawn on 15 December 1890, the life of Sitting Bull, a chief and holy man of the Hunkpapa Lakota Indians, came to an end, shot in the chest and head by Indian police who had come to arrest him. Sitting Bull was murdered by Indians sent by white men – who wanted him destroyed because they feared his waning but still powerful influence among the Lakota.

In his 59 years, Sitting Bull led a remarkable life. As a young man he was a fierce warrior, and later as a powerful and respected holy man he presided over the large Indian camp that annihilated George Armstrong Custer and his troops at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. Refusing to surrender to the whites and accept reservation life, Sitting Bull led his band into the safety of Canada in May 1877.

Four years later, however, destitution and hunger drove them to finally give up, and Sitting Bull and his band returned to the U.S. and surrendered on 19 July 1881, and tried to adapt to reservation life. The Lakota chief participated in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show for four months in 1885.

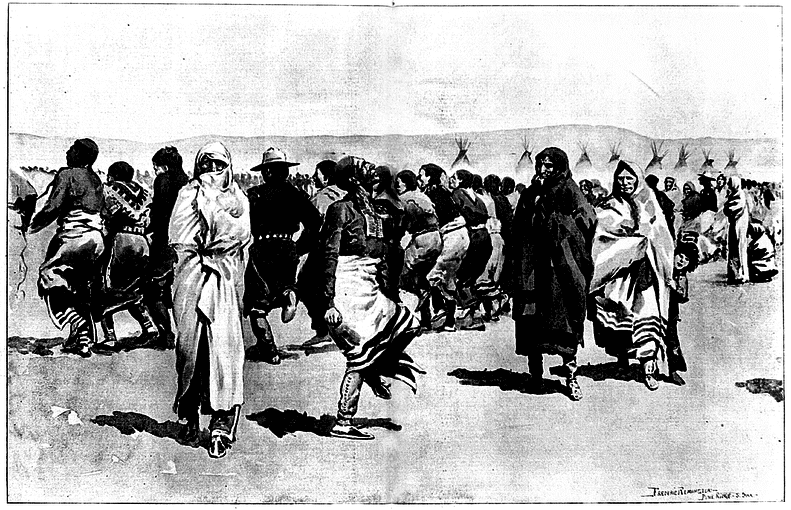

In 1890, the Ghost Dance came to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota and was embraced by some of the Lakota, including Sitting Bull. Part of the belief underlying this ritualistic dance was that all the dearly beloved dead Lakota would return, the earth would be rolled up, and underneath would be a beautiful, clean world with the buffalo herds restored and the white men gone.

James McLaughlin, the Indian agent at the Standing Rock Agency, was opposed to the Ghost Dance. Shortly before Sitting Bull’s murder, McLaughlin visited the chief and warned him to stop the Ghost Dance. His report of this visit is contained in the newspaper article reprinted below. Note that McLaughlin refers to the “ghost dance craze” while Sitting Bull calls it part of their “medicine practices.”

Two parts of McLaughlin’s report are especially chilling. In its conclusion he asserts that he is “confident” he can “break up the power of Sitting Bull.” Shortly after, he ordered the arrest that led to Sitting Bull’s murder. Another ominous comment is his description that when he last saw Sitting Bull and his followers, he “assured them of what this absurd craze would lead to and the chastisement that would certainly follow if these demoralizing dances and disregard of the department orders were not soon discontinued.”

Two weeks later Sitting Bull’s half-brother Big Foot and his band were slaughtered at the infamous Wounded Knee massacre on 29 December 1890.

Agent McLaughlin’s report was contained in the newspaper article announcing Sitting Bull’s death that the Aberdeen Daily News printed on its front page.

Here is a transcription of this article:

To His Fathers.

Sitting Bull Is Sent to the Happy Hunting Grounds by the Indian Police.

In the Melee Several Are Killed on Both Sides Including the Chieftain’s Son.

Full Particulars of the Affair as Confirmed by Indian Agent McLaughlin.

The Agent’s Last Interview with the Wily and Treacherous Old Chief.

The Story Goes That He Has Been Killed in a Fight with the Indian Police.

St. Paul, Dec. 15. – The report was received in this city this afternoon that Sitting Bull had been killed by the Indian police who had arrested him at his camp on Grand River. Gen. Miles later received a message from Pierre stating that Sitting Bull and his son had been killed. Another dispatch received at the army headquarters by Gen. Miles gave the particulars of the killing as far as known. This morning the Indian police started out to arrest Sitting Bull, having understood he proposed starting for the Bad Lands at once. A troop of cavalry under Capt. Fouchett and infantry under Col. Drum followed to support the police in case of necessity. When the police reached Sitting Bull’s camp, about forty miles from Standing Rock, they found arrangements being made for departure. The police arrested [Sitting] Bull and started back with him before the soldiers had arrived, the infantry not having made much more than half the distance at the time and the cavalry being some distance back. The old chief’s followers rallied quickly and tried to effect his recapture. In the fight that ensued Sitting Bull is said to have been killed and five Indian police were also killed. One of the Indian police jumped on a horse belonging to Sitting Bull and rode back to the cavalry and infantry, telling them to hurry up to the support of the police, and then hurried on to the agency with the news of the battle.

Confirmed by McLaughlin.

Washington, Dec. 15. – Indian Commissioner Morgan this evening received from Indian Agent McLaughlin the following dispatch dated Fort Yates, N.D., Dec. 15.

“The Indian police arrested Sitting Bull at his camp, forty miles southwest of the agency, this morning at daylight. His followers attempted his rescue, and fighting commenced. Four policemen were killed and three wounded. Eight Indians were killed, including Sitting Bull and his son, Crow Foot, and several others wounded. The police were surrounded for some time, but maintained their ground until relieved by the United States troops, who now have possession of Sitting Bull’s camp, with all the women, children and property. Sitting Bull’s followers, probably one hundred men, deserted their families and fled west up the Grand River. The police behaved nobly, and much credit is due them. Particulars by mail.”

Commissioner Morgan showed this telegram to the president late this evening. The president said he had regarded Sitting Bull as a great disturbing element in his tribe and now that he was out of the way he hoped a settlement of difficulties could be reached without further bloodshed.

An Official Dispatch.

Chicago, Dec. 15. – At 9 o’clock tonight Assistant Adjutant General Corbin, of Gen. Miles’ staff, received an official dispatch from St. Paul saying that Sitting Bull and five of his men, and seven of the Indian police, have been killed. The casualties were the result of the attempt by the police to arrest Sitting Bull.

The Agent’s Last Visit.

Chicago, Dec. 15. – The story of the last visit paid by a white man to Sitting Bull’s camp prior to the tragic events of today is told in a report received this afternoon by Assistant Adjutant General Corbin. The narrative throws a flood of light on the old chief’s wily character and strongly depicts the circumstances existing in the isolated camp. The document is addressed to Commissioner of Indian Affairs Morgan, by United States Indian Agent James McLaughlin, of Standing Rock, and reads in full as follows:

“Having just returned from the Grand River district, and referring to my former communication regarding the ghost dance craze among the Indians, I have the honor to report that on Saturday evening last I learned that such dance was in progress in Sitting Bull’s camp, and that a large number of Indians of the Grand River settlements were participators. Sitting Bull’s camp is on Grand River, forty miles from the agency, in a section of country outside of the line of travel, only visited by those connected with the Indian service, and is therefore a secluded place for these scenes. I concluded to take them by surprise, and on Sunday morning left for that settlement, accompanied by Louis Primeau. Arriving there about 3 p.m. and having left the road usually traveled by me in visiting the settlement, I got upon them unexpectedly and found the ghost dance at its height. There were about forty-five men, twenty-five women, twenty-five boys and ten girls participating. A majority of the latter (the boys and girls) were until a few weeks ago pupils of the day schools of the Grand River settlements. There were approximately 200 persons, lookers-on, who had come to witness the ceremony, either from curiosity or sympathy, most of whom had their families with them and had encamped in the neighborhood. I did not attempt to stop their going on as in their crazed condition it would have been useless. But after remaining some time talking with a number of spectators, I went on to the house of Henry Bullhead, three miles distant, where I remained overnight and returned to Sitting Bull’s house next morning where I had a long talk with Sitting Bull and a number of his followers. I spoke very plainly to them, pointing out to them what had been done by the government for the Sioux people, and how this faction by their present conduct were abusing the confidence that had been reposed in them by the government in its magnanimity in granting them full amnesty for all past offenses, when from destitution and imminent starvation they were compelled to surrender as prisoners of war in 1880 and 1881, and I dwelt at length upon what was being done in the way of education of their children and for their own industrial advancement and assured them of what this absurd craze would lead to and the chastisement that would certainly follow if these demoralizing dances and disregard of the department orders were not soon discontinued. I spoke with feeling and earnestness and my talk was well received, and I am convinced it had a good effect.

“Sitting Bull, while being very obstinate and at first inclined to assume the role of ‘big chief” before his followers, finally admitted the truth of my reasoning and said he believed me to be a friend of the Indians as a people but I did not like him personally, and that when in doubt in any matter in following my advice he had always found it well, and now he had a proposition to make to me, which if I agreed to, and would carry out, it would allay all further excitement among the Sioux over this ghost dance, or else convince me of the truth of the belief of the Indians in this new doctrine. He then stated his proposition, which was that I should accompany him on a journey from this agency to each of the other tribes of Indians through which the story of the Indian Messiah had been brought, and when he reached the last tribe, or where it originated, if they could not produce the man who started the story, and we did not find the new Messiah as described upon earth, together with dead Indians returning to re-inhabit this country, he would return convinced that they (the Indians) had been too credulous and imposed upon, which report from him would satisfy the Sioux and all practices of the ghost societies would cease, but that if they found it to be as professed by the Indians, they be permitted to continue their medicine practices and organize as they are now endeavoring to. I told him that this proposition was a novel one, but that the attempt to carry it out would be similar to the attempt to catch up with the wind that blew last year, but that I wished him to come to my house, where I would give him a whole night or day and night in which time I thought I would convince him of the absurdity of this foolish craze and the fact of his making the proposition he did was convincing proof he did not fully believe in what he was professing and endeavoring so hard to make the others believe. He did not, however, promise fully to come into the agency to discuss the matter, but said he would consider my talk and would decide after deliberation. I consumed three days in making this trip and felt well repaid by what I accomplished, as my presence in their midst encouraged the weaker and doubting and set those who are believers to thinking of the advisability of continuing these nonsensical practices they are now engaged in. I also found the active members in the dance were not more than half the number of the earlier dancers, and I believe it is losing ground among the Indians and while there are many half believers, I am fully satisfied I can keep the dances contained to the Grand River district. Desiring to use every reasonable means to bring Sitting Bull and his followers to abandon this dance and to look upon its practice as detrimental to their individual interests and welfare of their children, I made the trip herein reported to ascertain the extent of the disaffection and the means of effecting its discontinuance. From closer observation I am convinced the dance can be broken up and after due reflection would respectfully suggest that in case my visit to Sitting Bull fails to bring him in to see me in regard to the matter as invited to do, all Indians living on the Grand River be notified that those wishing to be known as opposed to the ghost doctrine, friendly to the government and desiring the support provided in the treaty, must report to the agency for such enrollment and be required to camp near the agency for a few weeks; and those selecting their medicine practices, in violation of the department orders, to remain on the Grand River from whom subsistence will be withheld. Something looking toward the breaking up of this craze must be done, and now that the cold weather is approaching, it is the proper time. Such a step as here suggested would leave Sitting Bull with but a few followers, as all or nearly all would report for enrollment, and thus he would be forced in himself. There are not many firearms among these Indians, still there are a few, and as a pledge of good faith on their part they should be required to turn in all their arms to the agent and get a memorandum receipt for the same.

“Knowing the Indians as I do, I am confident that I can, by such course, settle the Messiah craze at this agency and also thus break up the power of Sitting Bull, without trouble and with but little excitement. This will be sustained by public sentiment and conform to the discipline approved by the better disposed Indians.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Are there Native Americans in your family tree? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles:

- Native American Genealogy: Research Tips & Resources

- Don’t You Wish the Census Had Pictures of Our Ancestors?