Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes about a controversy in Salem, Massachusetts, over the treatment of some Quaker tombs. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Author’s Note: I came across this story while researching the 17th century Quaker families in Salem, Massachusetts. They are the ancestors of the tombs in Salem that are the focus of today’s story. A list of these Salem Quakers can be found in Jonathan M. Chu’s book Neighbors, Friends, or Madmen: The Puritan Adjustment to Quakerism in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts Bay (p. 169-173). These Quakers are also cited in the court documents available online at the University of Virginia site.

In 1835 the Board of Health in Salem placed an announcement in the newspaper which created a sensation. The board reported that several tombs in public burial grounds were in a ruinous state, and requested owners to come forward to mark the appropriate names and fix up the tombs. For tombs left unclaimed or undefined, the board announced that it would repair – and then sell – those tombs.

As you can imagine, this sent the community into a tizzy. This very grave matter was the talk of the town – and when the tombs’ descendants got word, they buried the board elders in the press!

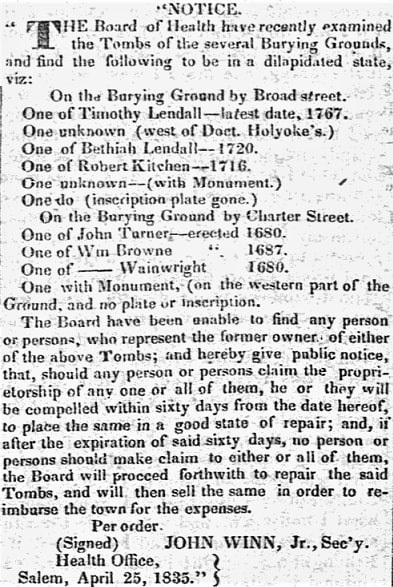

The shocking announcement was published in the Salem Gazette on 25 April 1835 by Board Secretary John Winn Jr.

This notice stated:

“The Board have been unable to find any person or persons who represent the former owner of either of the above Tombs; and hereby give public notice, that, should any person or persons claim the proprietorship of any one or all of them, he or they will be compelled within sixty days from the date hereof, to place the same in a good state of repair; and, if after the expiration of said sixty days, no person or persons should make claim to either or all of them, the Board will proceed forthwith to repair the said Tombs, and will then sell the same in order to reimburse the town for the expenses.”

After some of the bodies had been removed in preparation for the sale of the tombs – and after reading an indignant letter to the editor from E. Hersey Derby – Jonathan Ingersoll Bowditch and Lucius Manlius Sargent came to the burying grounds to examine what had been done, and published their report in the Salem Gazette. In their introductory paragraph, “the undersigned” refers to Bowditch and Sargent.

As part of their report, Bowditch and Sargent quoted from Derby’s letter:

“In the same paper I noticed an advertisement, signed by John Winn Jr., stating that on several burying grounds a considerable number of tombs were without monumental or other inscriptions. As my wife and children are the last survivors of this ancient family remaining in town, I felt it a duty to visit the grounds to see the state of the Browne tomb. Judge of my horror, as I approached the spot, where a few short years [before] I had myself deposited the beloved remains of near and dear connections of that venerable family, so recently that their grave clothes have hardly had time to decay, to find that it had been opened by some sacrilegious hands, the coffins broken up and removed, and the remains of the bodies apparently laying on the ground exposed to the dogs of the field and the winds of heaven, with only a slight covering of earth. What inducement does this hold out to persons to contribute in any way for the benefit of this ancient town? Can this sacrilege have been permitted by any of the authorities of the town, with the paltry view of selling the tomb to some other individuals, whose descendants may in like manner have their feelings outraged; or can it be done by some monster in human shape, for the purpose of pillaging the mortal remains of one of the most wealthy and highly respectable families that ever resided in Salem? I ask of the public, as a fellow citizen, if this outrage is to be permitted?”

Like Derby, Bowditch and Sargent were also horrified by what they found in the burying grounds, as they reported.

One of the tombs they examined was that of Timothy Lindall, an ancestor of Thomas L. Winthrop. They found a “few loose bones” but discovered “the interior of the tomb was in a perfect condition.” The inscription was clearly legible, “as fresh as if it were executed but yesterday”:

“Here lye the bodies of Timothy Lindall, Esq. aged 82 years, deceased Oct. 25, A. D. 1760; Bethiah his wife, aged 31 years, deceased June 20, A. D. 1720; Mary, daughter of Timothy and Bethiah, aged 22, deceased Dec. 31, A. D. 1740; Mary, [second] wife of Timothy, aged 80 years, deceased Feb. 8, A. D. 1767.”

Genealogy Note: Timothy Lindall, son of Timothy Lindall and Mary Vernen, married Bethiah Kitchen, daughter of Robert Kitchen and Bethiah Weld. Their daughter Mary died in 1740. After Bethiah died, Timothy married Madame Mary Henchman of Lynn, who died seven years after Timothy, in 1767.

They discovered the tomb of Robert Kitchen “was remarkably sound within,” and also found the inscription for the tomb was perfectly legible:

“Here lies interred the body of Mr. Robert Kitchen, who departed this life Oct. 28, 1712, [age] 56. Here lies interred the body of Robert Kitchen, son of Mr. Robert and Bethiah, a student of Harvard College in Cambridge, aged 17 years, departed this life Sept. 20, 1716.”

Genealogy Note: Robert Kitchen, died 1712, son of John Kitchen and Elizabeth Grafton, married Bethiah Weld. Children: Bethiah married Timothy Lindall; Robert died in 1716; and Edward married Feke Wolcott. He married 2nd Mary Boardman, and daughter Mary Kitchen married John Turner.

Stay tuned for more about these tombs.

Note: the photo in the top banner is credited to Robert Buckley.