Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry describes the fashion laws in effect in 17th century Massachusetts – and how both women and men flaunted the law. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Author’s Note: This article is extracted from my “Daily News Newburyport” story about sumptuary laws published back on 23 June 2013, but GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives provided more articles and I am stepping it up a notch.

A popular article published in 1895 was “The Law and Woman’s Dress,” which ran in many newspapers across the country. Do not be fooled, Lads – you were mentioned here too, and the early court records are loaded with your fashion transgressions.

Our Puritan ancestors’ foibles reveal that human nature is no different today. In the Bay Colony, leaders and church officials waged a campaign of rigid scrutiny, censoring the lifestyle and habits of everyday citizens. Simplicity in dress was the law – but like any other infringement on personal liberties carried out in the name of God, these sanctions would not go down without a struggle. A fashion war raged, and it seems that the legislature could no more ban fashion than it could heretics or tipplers.

In seventeenth century Massachusetts, the men of the cloth pleaded to Governor Winthrop to repress “men of leisure and power” who emulated London fashions, spoiling the pure terrain. These “horrids of vanity” caused “alarm and disgust among the pious families.”

To remedy this, “The Simple Cobler of Aggawam,” published by Rev. Nathaniel Ward, targeted the colony’s ladies, stating they had “no true grace or valuable virtue” if they “disfigure themselves with such exotic garbs” and are no better than “French flirts.”

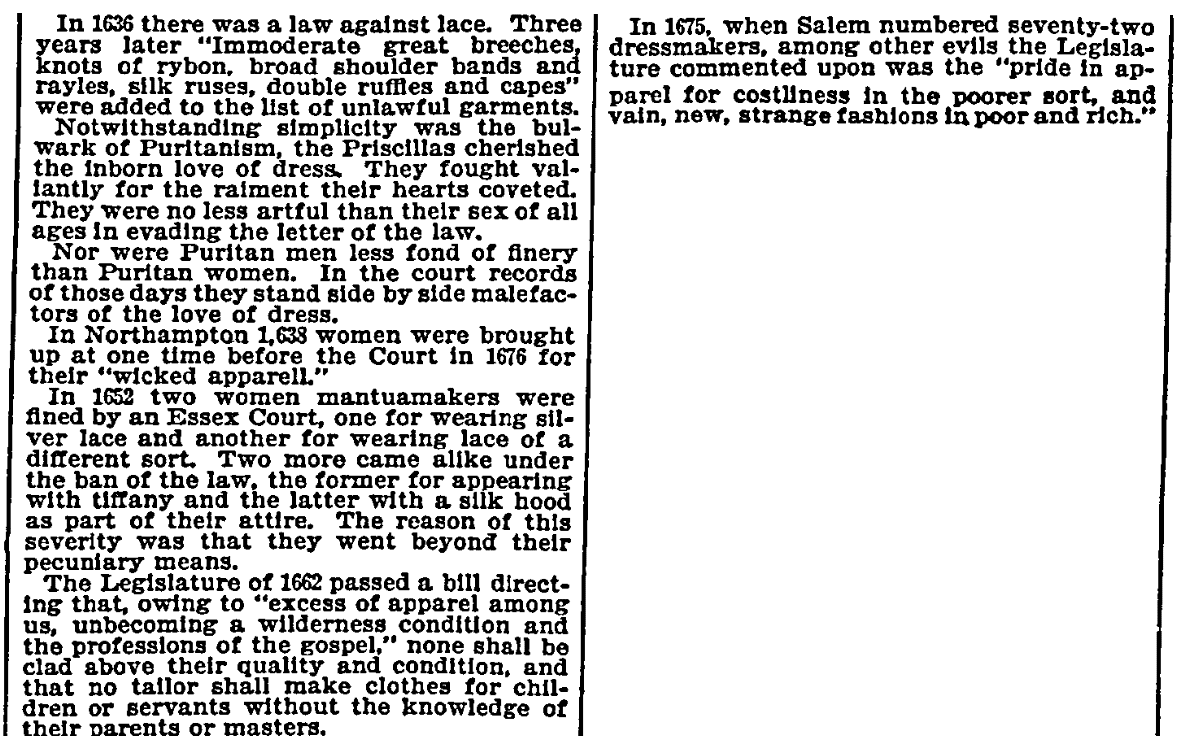

The holy rollers used sermons to blame these so-called “haughty women” for wars and bad harvests. The magistrates began enforcing sumptuary laws that prevented extravagance by limiting clothing expenditures. “Immodest fashions” with lace, silver, gold thread and other “items of adornment” that had “little use or benefit, but to the nourishment of pride,” were strictly forbidden, as were “slashed apparel, great sleeves, great boots, ribbon, and double ruffs.”

In 1636, a law forbidding lace – except for the upper class – was passed, and next came prohibitions against “great britches, knots of rybon, broad shoulder bands, double ruffles, and capes.” Despite these laws, garments of splendor and other wearable loot poured in – historical records show that our ancestors were quite stylish.

The most notorious of the “Vanity Fair” was Madame Rebecka (Swayne) Symonds, widow of Deputy Governor Samuel Symonds. Madame had three marriages before she tied the knot with Samuel, and all were beneficial to her purse and wardrobe budget. She was always starving for the newest trends, and she had the means and the connections to stock her trunks.

Family letters reveal her appetite for finery. Her son John, born from a marriage to John Hall, a wealthy London merchant, dutifully supplied her with the latest and most glamorous garb. Apparently, Madame was more worried about catching the plague than tweaking the noses of local lawmen. Her luxury booty arrived with correspondence from Hall assuring her that he purchased the “finery himself, in safe shops, from reliable dealers, and kept all for a month in his own home where none had been infected.”

The family letters are housed in the American Antiquarian Society and referenced in Alice Morse Earles’ book Two Centuries of Costume in America, Volume 1. Though her garments carried no contagious germs, Madame Symonds was surely dressed to kill that season. And she wasn’t the only one.

Judge Samuel Sewall, on the prowl for a wife, set his sights on the widow of Samuel Ruggles: Martha Woodbridge, daughter of Rev. John Woodbridge and Mercy Dudley and granddaughter of Gov. Thomas Dudley. Samuel not only adored her pedigree, but her chic garb as well. He wrote to Martha’s brother, Rev. Thomas Woodbridge of Connecticut, noting fond memories of Martha’s great style:

“I have sometime met your Sisters Martha and Mary, at the end of Mrs. Noyes’s Lane, coming from their Schoole at Chandler’s Lane, in their Hanging Sleeves; and have had the pleasure of Speaking with them: And I could find in my heart to speak with Mrs. Martha again, now I my self am reduc’d to my Hanging Sleeves. The truth is, I have little Occasion for a Wife, but for the sake of Modesty, and to cherish me in my advanced years (I was born March 25, 1652). Methinks I could venture to lay my Weary head in her Lap, if it might be brought to pass upon Honest Conditions; you know your Sister’s Age, and Disposition, and Circumstances better than I do. I should be glad of your Advice in my Fluctuations.”

The word got back to Martha, but she was not impressed – this fellow was never going to get under her sleeves. His diary notes his attempts, and after Martha rejected his two proposals, he moved on to woo Widow Gibbs.

While the genteel usually got a minor shunning for their extravagance, for colonists with a yearly income of less than 200 pounds, wearing the style of polite society was criminal. To give falsehood of your station in the Puritan Republic was against God’s law. The General Court announced its “utter detestation and dislike” that “over-proud commoners” of “mean condition, education and callings should take upon them the garb of gentlemen.” Infractions resulted in punishment and fines. Tailors were forbidden from making garments “contrary to the mind and order of the Governors,” and if the grand jurors failed to bring indictments against guilty persons, the courts would impose fines on them.

In 1653, Jonas Fairbanks and Robert Edwards were charged for wearing “great boots,” a cavalier fashion of excessive leather. John Chubb was admonished for “excess in apparel, beyond that of a man of his degree.” Henry Bullock and Mark Haskall of Salem, Massachusetts, were fined for their “excess in apparel in boots, ribbons, gold and silver.” In Ipswich, George Palmer was fined 10s. for wearing silver lace, and Samuel Brocklebank for the same, but discharged due to his higher station of income.

The writer of this 1828 letter to the editor, identified only as “Y.,” told the story of Jonas Fairbanks and his offensive boots, and reveals a more tolerable attitude than was prevalent in the 1600s:

“Yes, Jonas was ambitious – ambitious of gaining distinction by dress… Could Jonas but be permitted to wear ‘great boots’ the measure of his ambition would have been satisfied. It would seem a very harmless thing to be indulged in this, and somewhat arbitrary to say to a citizen of goodly leg ‘walk not in great boots.’”

No one was safe from the fashion police. Ipswich’s Arthur Abbott, agent who dispensed the fine dress goods to Madame Symonds via her son in London, could not dodge a fine slapped on his wife, Elizabeth (White) Abbott, for the public wearing of a silk hood. He “cheerfully” paid 10s. to the court – no doubt he liked his wife in the fine silk styled in the London fashion after Madame Pepys.

Here are a few records (1653-1677) from the Quarterly Courts of Essex County and Massachusetts Town Records regarding residents’ fashion violations. Note how often violators were excused, or “discharged,” because they were wealthy.

- Wife(s) of John Hutchings, Thomas Harris, Thomas Wayte and Edward Browne, presented for wearing a silk hood, all discharged, testimony being brought up that they were above the ordinary rank and upon proof of their education.

- Wife(s) of Nicholas Noyes, Hugh March and John Whipple, presented for silk hood and scarves, but discharged for being worth 200 pounds.

- Wife(s) of William Chandlour and Joseph Swett, fined ten shillings for wearing a silk hood.

- Agnes, wife of Deacon Knight, presented for wearing a silk hood, discharged, her husband being worth above 200. (This troubled the good deacon exceedingly and induced him to solicit Mr. Rawson to send a letter to one of the magistrates at Salem.)

- Hannah Bosworth’s two daughters of Haverhill, Massachusetts, fined 10s. each for wearing silk.

- Margaret Lambert fined 10s. for “going in a genttel garbe.”

- Hannah Westcarr presented “for wearing silk in a flaunting garb to the great offence of several sober persons in Hadley.”

- The wives of Joseph Gaylord and Thomas Selding, for wearing silk contrary to law, wearing it “in a flaunting manner, and excess of apparel to the offence of sober people.”

The boldest of the females was sixteen-year-old Hannah Lyman, daughter of Richard Lyman, of Northampton, deceased. She was presented in September 1676 “for wearing of silk in a flaunting manner, in an offensive garbe.” Hannah must have been styling, as she caught the eye of Joseph Pomeroy and the two married that year in June.

Many, like Hannah, just would not conform, nor be controlled – and in this story, she gets the best-dressed trail blazer!

A Big Thank You to historian Richard Trask, Danvers, Massachusetts, archivist.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Further Reads:

- GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives

- Alice Morse Earle. “Two Centuries of Costume in America Volume 1,” 1903.

- Jonas Fairbanks (1625-1676) Wearing Great Boots Contrary to the Law. Theme: “Independence.”