When Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run on 8 April 1974, it was a historic achievement on two levels. For one, he broke what was considered the greatest record in all of sports, the 714 home runs hit by Babe Ruth, the “Sultan of Swing.” Aaron’s achievement was more than just a sports accomplishment, however – the vicious outpouring of hate mail combined with the adoring, buoyant support he received said a great deal about America as an African American broke a hallowed record set by a white man.

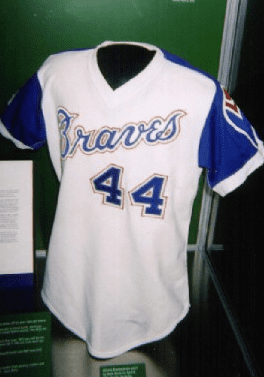

The case could easily be made that Henry “Hank” Aaron was the greatest player of all time. In 23 remarkable seasons, he hit 755 home runs – acknowledged by baseball purists as the career home run record, since Barry Bonds’ 762 were artificially achieved with the chemical boost of steroids. Aaron is the indisputable holder of other remarkable career records: 2,297 RBI, 6,856 total bases, and 1,477 extra base hits. He was a World Series champion, a Most Valuable Player, an All Star 25 times (the game was held twice a few years), and won three gold gloves.

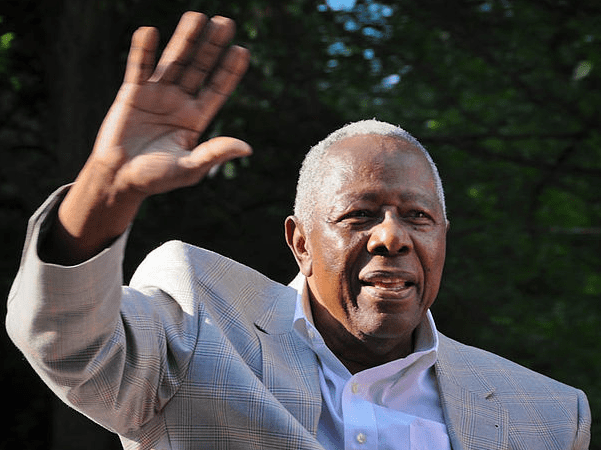

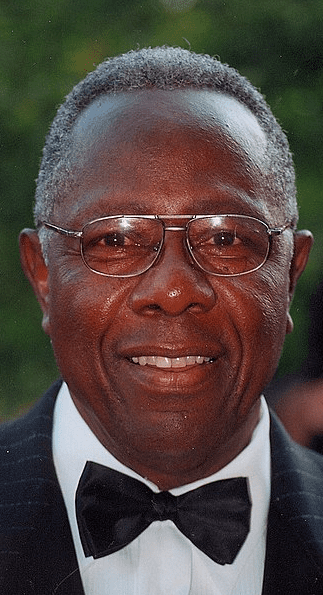

Throughout this remarkable career, Aaron conducted himself with grace and dignity, a true gentleman on and off the playing field.

Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, and many fans feared a racist would assassinate him during the offseason to prevent him from breaking Ruth’s record. The amount of vile, vicious hate mail increased, with many threats made on his life. The 1974 season began with controversy, as Aaron’s team, the Atlanta Braves, opened with three games in Cincinnati. The Braves wanted Aaron to sit those games out and begin the season in Atlanta, so that he could hit the tying and record-setting home runs in front of a home crowd. In a controversial move, Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn ordered Aaron to play at least two of the three games in Cincinnati, which he did – hitting the tying 714th home run on his very first at bat, but no more that series.

And so, the stage was set for Aaron’s return to Atlanta. The milestone came before a huge, enthusiastic sellout crowd of 53,775. Aaron walked in his first at-bat that evening, not swinging during the four-ball, one-strike at-bat. He was next up during the fourth inning.

The excited crowd waited as the 40-year-old slugger stood in against his opponent, the Dodgers’ 32-year-old southpaw Al Downing. The first pitch was a ball. On the next pitch, a fastball, Aaron swung his bat precisely at 9:07 p.m. and launched the historic home run 400 feet into the Atlanta night, and straight into the record books.

The following two newspaper articles describe the two aspects of Aaron’s historic achievement. The first is a news report of the home run itself, and the second is an interview with Aaron in which he focuses more on the issues facing African Americans in this country than his home run.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Hank Hammers Historic 715

ATLANTA (AP) – “If God didn’t see fit for me to hit the home run here, then I would have hit it somewhere else,” Henry Aaron said Monday night after becoming baseball’s all-time home run king.

The reserved 40-year-old superstar was obviously relieved that the chase of the legendary Babe Ruth had finally ended.

It did at exactly 9:07 p.m. EDT. Aaron connected for the historic 715th home run off Al Downing of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

The two-run blast, a 400-foot shot, sailed out of a jam-packed Atlanta Stadium, just to the right of the 385-foot marker in the fourth inning, giving the Braves a 3-3 tie at the time.

Atlanta went on to win the game 7-4.

Aaron opened his post-game news conference by criticizing unnamed writers for questioning his performance during a three-game season-opening series in Cincinnati.

“I have never went out on a ball field and not given my level best,” he said. “I played in Cincinnati the two out of three games I was supposed to play.

“Contrary to some of the reports I have read that I was a disgrace to the ball club, I did my level best.”

Aaron declined to say what written reports had been critical of him.

The legendary Ruth, who died of cancer in 1948, hit the last three of his 714 home runs on May 25, 1935, against the Pittsburgh Pirates. At the time, he was with the Boston Braves.

Ruth played in 2,503 games and had 8,399 at-bats during his 22-year career. He quit the game in a dispute with Boston management about a week after hitting his final homers.

Aaron’s historic 715th homer came in the third game of his 21st season. It was his 11,295th at-bat – all with the Braves – and his 2,967th game.

“Just thank God it’s all over,” Aaron said as the standing-room only crowd of 53,775 – largest ever to see a baseball game in Atlanta – roared continuously.

Aaron, who had walked on five pitches – taking the only strike – in a second-inning trip to the plate, jumped on a 1-0 fastball by the 32-year-old Dodger lefthander.

“He just hung it a little,” Aaron said. “It was inside, but I think he wanted it further inside.”

“When he picks his pitch, he’s pretty certain that’s the one he wants,” Downing said, noting that Aaron’s historic blast had come on his first swing of the night.

The Atlanta slugger had tied Ruth’s record on the first swing of the 1974 season, a three-run shot in Cincinnati last Thursday off righthander Jack Billingham.

The huge crowd began buzzing the moment the ball left Aaron’s bat, and when it sailed over the fence, bedlam erupted.

As Aaron circled the bases in typical fashion, a massive fireworks display was triggered, sending colored sparks into the air along with cannon-like noises.

It was one of his teammates, pitcher Tom House, who caught the ball and rushed it to Aaron as the game was halted for an 11-minute tribute.

Aaron broke away from his mates and rushed to a special box adjacent to the Atlanta dugout where he clutched his wife, Billye, and parents, Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Aaron, of Mobile, Ala.

“I never knew she could hug so tight,” Aaron said of his mother.

His father, who threw out the first ball, jumped out of the special box and joined his famous son on the field for a special presentation from the commissioner of baseball, Bowie Kuhn.

Kuhn, who had ordered Aaron to play in Sunday’s game at Cincinnati, was not here, but had one of his aides, black Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, give the Atlanta superstar a $3,000 diamond-studded wristwatch upon which was imprinted in gold the figure 715.

When Irvin mentioned the commissioner’s office, the crowd booed loudly.

Kuhn was in Cleveland attending a dinner. He said he did not see Aaron’s homer, but heard about it moments later.

President Nixon telephoned Aaron congratulations almost immediately.

“The president just invited me to the White House and he congratulated me,” Aaron said. “No, he didn’t mention any specific date.”

Nixon’s call came while Aaron was in left field. Manager Eddie Mathews gave his star permission to leave the dugout to talk with the president.

Aaron was asked if he felt he would hit the home run in this game.

“Yes, I did,” he said.

Asked what it meant to him to break the record, he said, “Well probably tomorrow morning, I’ll wake up and realize what happened. Right now, it’s just another home run. The most important thing is we won the game.”

Aaron’s wife sat by his side as he fielded questions from an estimated 200 newsmen.

Asked her feelings, the Atlanta television hostess said, “I had mixed emotions about 714. I wanted him to hit it at home. I would have preferred hits to home runs in Cincinnati.”

It was only Aaron’s third home run off Downing, beginning his fourth year in the National League. The others came last season – No. 676 in Los Angeles on April 15 and No. 693 in Atlanta on June 29.

In his next appearance after his home run, Aaron grounded out to third base in the fifth inning. The pitcher at the time was righthander Mike Marshall.

His first run of the night set a National League record of 2,063, moving him ahead of fellow Alabama native Willie Mays, who retired last year.

Here is a transcription of this article:

What Pursuit of Record Has Meant for Hank: People Listen

By Ira Berkow

ATLANTA (NEA) – What has THAT record, THE record, meant to Henry Aaron, the man who was almost certain to break it?

“It has meant,” he says, sitting with sawed-off blue sweatshirt before his locker cubicle, “that people listen to me now where, say, 10 years ago, my words got lost.”

Only in the last two years has Aaron begun to receive the national recognition that his phenomenal career has so richly deserved. Only, that is, since his pursuit of the career home run record held by Babe Ruth has brought him inescapably, finally, into the limelight.

People listen to him because they are watching him. And it becomes of great interest to know what kind of man he is. He also is greatly aware of this: “Ruth’s record is about the last thing in professional sports that whites can hang onto – the legendary record of the Sultan of Swat,” he says.

He has recently become identified with black causes. For example, he is now a close personal friend of the Rev. Jesse Jackson, a leading young black spokesman. Aaron, in winter, now is the organizer of a celebrity bowling tournament in Atlanta with proceeds going to research on sickle cell anemia, a disease that afflicts black people.

Aaron is also outspoken on the progress, or lack of it, for blacks in baseball. He says that blacks are stagnating. “Whatever so-called progress there is – like blacks staying in the same hotels with the white players – this came about from civil rights legislation, not from any leveling action by baseball,” says Aaron.

“Why aren’t there even no black managers? Why aren’t there even no black third base coaches? There are token first base coaches – a few. But what does a first base coach do? He has no duties. No responsibilities. Nothing. Absolutely nothing. He’s not expected to have any intelligence.”

Aaron still feels some of the clichés of being black. He remembers that once blacks were considered “too gutless” to be able to take the pressures of day-in, day-out major league baseball.

“Jackie Robinson changed a lot of those beliefs,” says Aaron. “His courage and intelligence showed what the black man could be made of.

“I hear about blacks having natural ability, natural rhythm. That’s not the only reason for the blacks’ success in baseball, or in sports. Look at a Maury Wills. It takes a lot of thought, a lot of analyzing, to steal 104 bases in a season.

“And you don’t hit over 700 home runs in a career by just having natural rhythm. You need discipline. You study the pitchers. I’m sure I know the National League pitchers as well as Ted Williams knew the American League pitchers when he batted .400.”

Aaron’s hero off the field is Dr. Martin Luther King. “He could walk with kings and talk with presidents,” said Aaron. “He wasn’t for lootings and bombings and fights but he wasn’t afraid of violence, either. He was 20 years ahead of his times.”

King’s death by assassination cannot, of course, be forgotten by Aaron. Sometimes Aaron wonders about that, too. He says that among the hundreds of letters he receives weekly, many are threats on his life.

“But I can’t think about that,” he says. “If I’m a target, then I’m a target. I can only worry about doing my job, and doing it good.”

Aaron believes that Ruth’s record should have been broken, just as it should someday be broken again.

“I think it’s good for all America,” he said. “The world keeps going on. Kids today can relate to me. And besides, why should they relate to a ball player who quit playing 35 years ago?

“I think it also gives black kids hope. It shows them that anything is possible today. Maybe they can’t be a ball player like me, but they can strive for excellence, and be a good doctor or lawyer or anything. I believe that I would have tried to be the best at whatever I did, even it if was being a dirt shoveler.”

It wasn’t that way for Aaron when he was a boy. He was the third child in a family of eight children in Mobile, Ala. His father was a rivet-bucker. Aaron played baseball but he had no hopes of making the game a career.

“There were no blacks in major league baseball until I was 13 or 14, and Jackie Robinson broke in in 1947,” said Aaron. “He gave us all hope.”

Aaron was asked about the coincidence that Babe Ruth died just one year later. Did his death at the time mean anything to Aaron?

“No, not really,” said Aaron. “Ruth was in a different world. Baseball when he played was something no black kid could relate to. We had nothing to wish for. You know, of all the pictures I’ve ever seen of Babe Ruth, I’ve never seen one with him and black kids. Have you? This is no knock on Ruth. It’s just the way it was. I don’t think many blacks went to the baseball games. It’s like I don’t go to ice hockey games, even though it might be a great sport. But I can’t relate because there are no blacks in that game.”

It was Robinson who allowed Aaron to “relate” to baseball. Aaron holds immense respect and gratitude for Robinson and his memory.

“Before Jackie died, in the days when he was going blind,” said Aaron, “we had long talks. I will never forget that he told me to keep talking about what makes me unhappy, to keep the pressure on. Otherwise, people will think you’re satisfied with the situation.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. The same is true of more recent news. Do you have memories of Hank Aaron beating Babe Ruth’s home run record?

Related Articles: