It’s nice to think that everyone is related—but as genealogists we have known that would be difficult to prove. Now science is proving that theory is correct.

A new DNA study shows that everyone alive on the earth today shares common ancestors only 1,000 to 2,000 years ago.

What?

“Group Hug!”

Wow—what is this study telling us?

It is saying that we are all related and that science can prove it.

How is that possible?

With every generation the number of our ancestors doubles. We have 4 grandparents; 8 great-grandparents; 16 2nd-great-grandparents, and so forth.

But as we go back in time the reverse is true: the number of people who were alive on the earth keeps growing smaller.

A new DNA study shows that all Europeans descend from the “same set of ancestors only a thousand years ago.” This theory has long been proposed, and it has commonly been said that “everyone” in Europe is a descendant of Charlemagne—or that every Englishman alive today has royal ancestry.

UC-Davis Professor Graham Coop says that “we now have concrete evidence from DNA data” that we are all related, and “it’s likely that everyone in the world is related over just the past few thousand years.” Read the entire article: Europeans All Related by Genetic Footprint Dating Back Only 1,000 Years Ago.

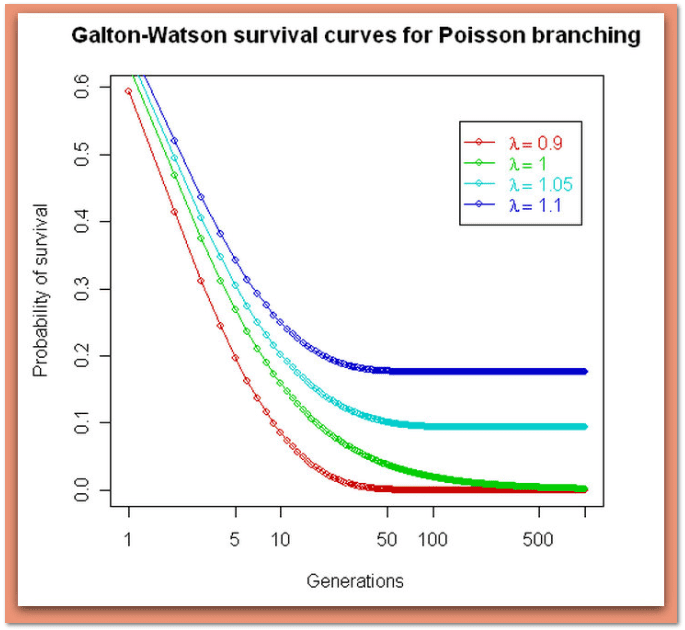

This interesting finding will revolutionize the way we view “family” in much the same way that the 1873/1874 Galton-Walton study changed our view of surnames 140 years ago.

Their pioneering work showed us that it was likely for a surname to go extinct after 12 to 20 generations. Assuming that each generation begins every 30 years, then 20 generations would extend back to the 1400s.

Click here to read their study “On the Probability of the Extinction of Families” published in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain, volume 4, pages 138–144, printed in 1875.

This interesting genealogy study concluded that any given family would eventually no longer have male descendants in the male, surname line. They might have hundreds or thousands of female heirs, but no male descendants carrying the surname after 12 to 20 generations.

Their probability research showed that with each generation it was possible, even likely, that in the next generations there would be no male children born to a given household, or that the male children born would die without surviving male children. They concluded that it was likely after 12 to 20 generations—with wars, disease, or simply by chance—that there would be no more surviving males who could marry and pass down the family name. In genealogy-speak this is referred to as daughtering-out.

From the probability theories of 140 years ago to the more exact science of DNA today, we genealogists are getting a lot more to consider as we trace our family history.