Introduction: In this article—written in celebration of the 240th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party—Mary Harrell-Sesniak tells the story of how one paragraph in an 1858 newspaper article provided the clue that led to one of her most satisfying genealogy moments. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

Researching your family history in old newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is a great way to fill in your family tree and find stories about your ancestors’ daily lives. Sometimes the most astounding discoveries one finds in newspapers aren’t about proving descent from an ancestor—but instead, they’re about finding your family’s place in history.

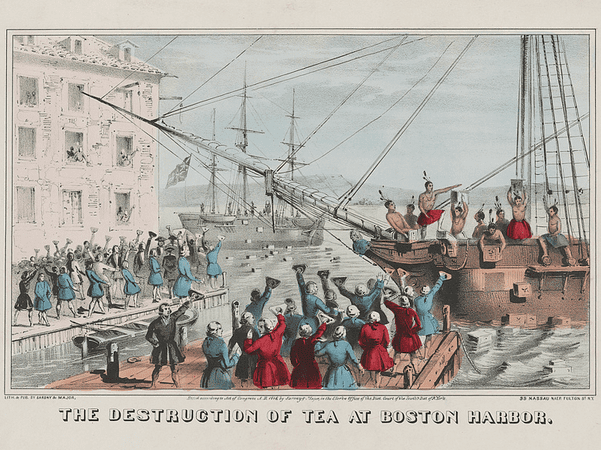

Boston Tea Party of 1773

I’ve been lucky to find more than my fair share of family history connected to important events in American history—especially the American Revolution. There is one particular event that has always held a special fascination for me: the Boston Tea Party of 16 December 1773. This famous political protest, when demonstrators boarded three British ships and dumped chests of tea into Boston Harbor to protest the tax levied by the hated Tea Act, was one of the events that led to the American Revolutionary War.

Many of the Boston Tea Party participants belonged to the “Sons of Liberty,” who were despised by the British. Even into the early 1800s, many “sons,” and even “Daughters of Liberty,” were afraid to disclose their secret support or participation in this group—often taking that secret to their graves.

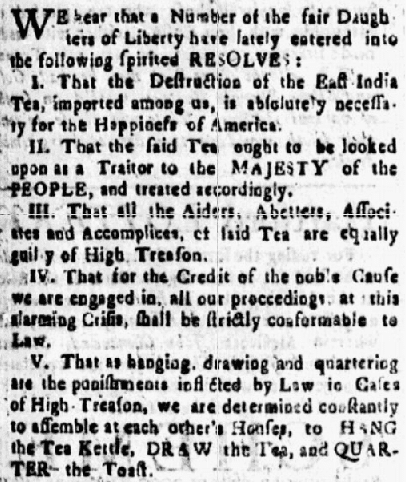

Shortly after the Boston Tea Party, some of the Daughters of Liberty entered into a “spirited” resolve, declaring: “That the Destruction of the East India Tea, imported among us, is absolutely necessary for the Happiness of America.” Knowing that their defiance of English law could be dangerous, they ended their resolution with the following declaration—with tongue firmly in cheek:

“That as hanging, drawing and quartering are the punishments inflicted by Law to Cases of High Treason, we are determined constantly to assemble at each other’s Houses, to HANG the tea kettle, DRAW the Tea, and QUARTER the Toast.”

I admit my fascination with the Boston Tea Party is an unusual interest, because for a long time I couldn’t uncover any family provenance connecting us to that eventful protest—yet my interest remained keen.

I knew all along there was more historical evidence to continue investigating. If you suspect your family had a connection to that event, be sure to review the list at the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museums website. It unfortunately does not include any of my forebears, but perhaps you’ll find someone in your tree.

My Revolutionary War Ancestors

Although my past genealogical research hadn’t been able to connect my family tree to the Boston Tea Party, my ancestors were involved in the American Revolutionary War. Two of my Patriot ancestors that fought in the war were from the Wilder family:

- Seth Wilder, Sr. (1739/40-1814), husband of Miriam Beal

- Seth Wilder, Jr. (1764-1813), husband of Tabitha (or Dorcas) Briggs

Both natives of Hingham, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, they later settled in Cummington, Hampshire County, Massachusetts. I don’t know with certainty why they left Hingham, but I found a 1773 newspaper article that perhaps provides the answer: a chimney fire entirely consumed their house when Seth, Jr. was only nine.

There are some brief accounts in the National Archives about the military service of at least one Seth Wilder, but none that corroborate the family provenance.

My mother wrote about our Wilder ancestors in two of our family history books that she published. This is what she wrote about Seth Wilder, Jr.:

“At the age of 16, Seth Wilder (Jr.) took his father’s place in the army, serving as a mechanic in the Revolution. He fought at Saratoga, Monmouth and Stony Point, being wounded at Stony Point. After the war, he settled on his father’s farm in Cummington. He died intestate.”

A biography written about Seth, Jr.’s grandson, John Thomas Wilder, reports that the reason the son took his father’s place in the fighting is because Seth, Sr. lost a leg at the Battle of Bunker Hill. If this story is correct, it is more likely that it occurred at a later date—since Seth, Jr. wasn’t 16 until 1780, closer to the end of the Revolutionary War.

Exciting Newspaper Discovery: Possible Family Connection to the Boston Tea Party!

Eager to learn more about these Patriot ancestors, I examined numerous records, books and newspapers.

One day I stumbled upon something exciting: an 1858 newspaper article indicating that Seth Wilder, Sr. might have participated in the Boston Tea Party!

This was a real “Aha!” genealogy moment—although the connection was not a certainty and required more research to confirm.

The old newspaper article reported that a Mrs. Jenks Kimball claimed to be the granddaughter of a “Seth Wilder of Hingham,”—but I didn’t have a “Mrs. Jenks Kimball” in my family tree.

Was she the granddaughter of my ancestor Seth Wilder, Sr. or possibly Seth Wilder, Jr.—or was she the daughter of another Seth Wilder not at all related to me?

If I could establish that she was part of my family tree, then the report that she had inherited “a steel tobacco box which was in the pocket of her grandfather…when he assisted in throwing overboard the tea in Boston harbor,” was exhilarating!

But who was Mrs. Jenks Kimball?

She wasn’t recorded in the famous Book of the Wilders: A Contribution to the History of the Wilders from 1497… written by Moses Hale Wilder in 1878.

This is where genealogy really gets fun: putting together the pieces, trying to solve the puzzle of my family history. That 1858 newspaper article gave me the clue I needed in order to unravel this genealogy mystery. After some diligent research, I finally found the evidence proving Mrs. Jenks Kimball was part of my family!

Evidence Tying All the Pieces Together

From the following sources, I was able to confirm that Mrs. Jenks Kimball (Betsey Bradley) was the daughter of Tamer Wilder—who in turn was the daughter of Seth Wilder, Sr.!

Mrs. Jenks Kimball’s lineage:

- Seth Wilder, Sr. & Miriam Beal

- Tamer Wilder & James Bradley

- Betsey Bradley & Jenks Kimball

The Vital Records of Cummington, Massachusetts (William W. Streeter & Daphne H. Morris, 1979), reports numerous Wilder family records, including:

- 30 May 1797: Tamer Wilder (daughter of Seth Wilder, Sr. and Miriam Beal) married James Bradley.

- The couple had three children, all born in Cummington: Royal, Betsey and Cynthia.

Vermont Vital Records, 1760-1954 (Database online at Familysearch.org):

- Jinks [sic] Kimball

- Marriage: 20 August 1820 in Pownal, Vermont

- Spouse: Betsey Bradley

1850 Adams, Berkshire, Massachusetts U.S. Federal Census:

- Jenks Kimball age 53

- Betsey Kimball age 56

After all those years of being keenly interested in the Boston Tea Party, it was enormously gratifying to finally establish that I have a direct family connection to that historic event. And I owe it all to the clue I unearthed in one paragraph of an 1858 newspaper article!

Newspapers really are tremendous sources of family history information that can help you discover ancestral connections you never knew you had. I hope this story of my personal genealogical discovery will inspire you to search old newspapers for your own family’s connections to history.

By the way—if any of you are interested in tracing your Revolutionary War ancestry, come join the Revolutionary War Research page on Facebook! See www.facebook.com/groups/RevWarRsch/.

And if any of you know what happened to the steel tobacco box or the salt cellar once in the possession of my ancestor Betsey (Bradley) Kimball, please let me know, as I’d really love to see them.