Introduction: In this article, Jane Hampton Cook – inspired by yesterday’s commemoration of Memorial Day – did some research to honor slain soldiers of the American Revolutionary War. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. Her works can be found at Janecook.com. She is also the host of Red, White, Blue and You.

Memorial Day became a national holiday in 1971 to honor those who died while serving in the U.S. military – but nearly 200 years earlier, John Adams had his own version of Memorial Day, which he described to his wife Abigail in a letter on 13 April 1777:

“I have spent an hour, this morning, in the congregation of the dead. I took a walk into the potter’s field, a burying ground between the new stone prison and the hospital, and I never in my whole life was affected with so much melancholy.”

The local Sexton told Adams that 2,000 soldiers had been buried in the cemetery at Sixth and Walnut Streets. Adams wrote his wife:

“The graves of the soldiers, who have been buried in this ground, from the hospital and bettering house, during the course of the last summer, fall, and winter, dead of the small pox, and camp diseases, are enough to make the heart of stone to melt away.”

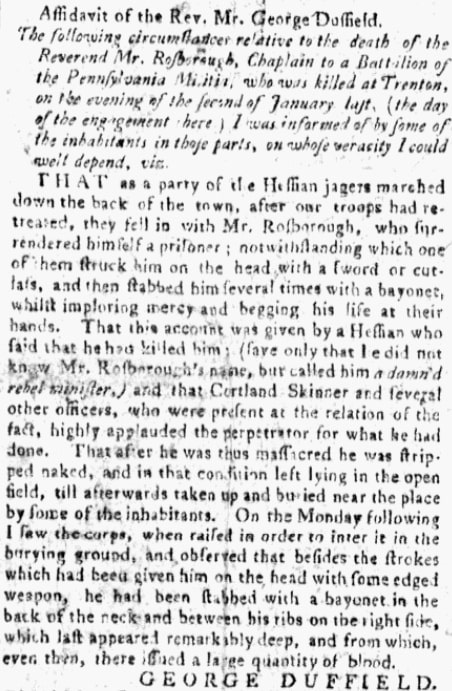

Two weeks later, on 29 April 1777, the Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet newspaper published an account of the burial of a member of the military whose death had violated the rules of warfare.

The Reverend George Duffield, a chaplain for the Continental Congress, reported on the death of Reverend Rosborough, a military chaplain assigned to a Pennsylvania battalion. He died on 2 January 1777, following the Battle of Trenton. Duffield’s sworn affidavit stated:

“That as a party of the Hessian jagers [hunters] marched down the back of the town, after our troops had retreated, they fell in with Mr. Rosborough, who surrendered himself a prisoner.”

The British had placed the Hessians (hired German fighters) at Trenton. The jagers were hunting for food when they came across Rosborough. Although they knew he was a minister and a chaplain when he surrendered, they showed him no mercy. Duffield stated:

“…one of them struck him [Rosborough] on the head with a sword or cutlass, and then stabbed him several times with a bayonet, whilst imploring mercy and begging [for] his life at their hands. That this account was given by a Hessian who said that he had killed him. (Save only that he did not know Mr. Rosborough’s name, but called him a damn’d rebel minister.)”

Their brutality increased after they killed him:

“That after he was thus massacred he was stripped naked, and in that condition left lying in the open field.”

Local residents buried the military chaplain nearby. Rosborough was one of the 6,800 men killed in action for the cause of American independence. Another 17,000 soldiers died of disease. In his letter to Abigail, John Adams wrote:

“Disease has destroyed ten men for us, where the sword of the enemy has killed one.”

Today that potter’s field in Philadelphia is known as Washington Square, where the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier is located. This memorial was created 14 years before Memorial Day became an official holiday.

This article reported:

“The remains of one of America’s first ‘GI Joes’ have been permanently enshrined here as a memorial to his comrades of the American Revolutionary War.”

“GI Joe” was a World War II slang name for a U.S. soldier.

Anthropologists had found the unmarked graves of several Revolutionary War soldiers on the square several months earlier. This article also reported:

“The plaque behind the tomb bears the memorial’s theme: ‘Freedom is a light for which many men have died in darkness.’”

The memorial also says:

“Beneath this stone rests a soldier of Washington’s army who died to give you liberty.”

From the American Revolution to today, Memorial Day gives us a chance to remember those known and unknown soldiers who died to both give us liberty and to keep it.