Introduction: In this article – to help celebrate Thanksgiving – Melissa Davenport Berry writes about the Mayflower Pilgrims’ very first Thanksgiving. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

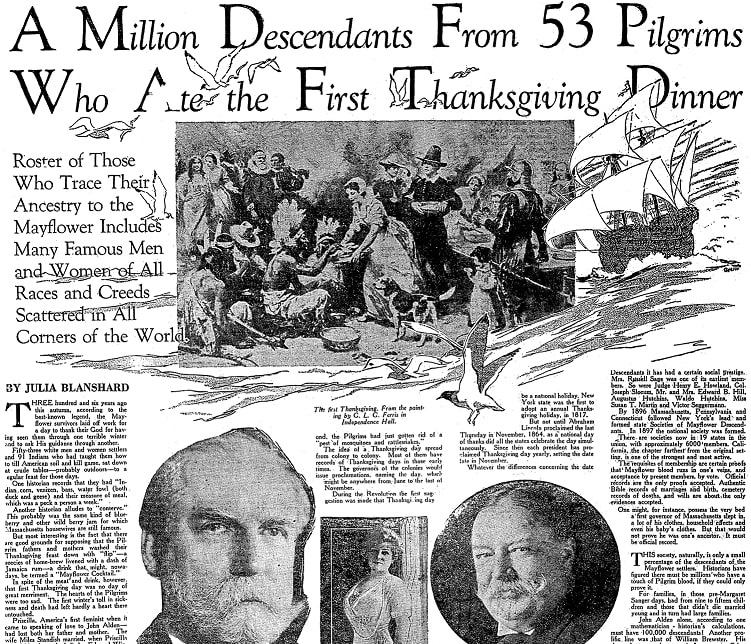

Today for a Thanksgiving treat, a slice of Mayflower history I found in the newspaper archives. Julia Blanchard’s article was published in the Evansville Press in 1927 with a headline that caught my eye: “A Million Descendants from 53 Pilgrims Who Ate the First Thanksgiving Dinner. Roster of Those Who Trace Their Ancestry to the Mayflower Includes Many Famous Men and Women of All Races and Creeds Scattered in All Corners of the World.”

This article reported:

Three hundred and six years ago this autumn, according to the best-known legend, the Mayflower survivors laid off work for a day to thank their God for having seen them through one terrible winter and to ask His guidance through another.

Fifty-three white men and women settlers and 91 Indians who had taught them how to till American soil and kill game, sat down at crude tables – probably outdoors – to a regular feast for those days.

One historian records they had “Indian corn, venizen, bass, waterfowl (both duck and geese) and their measure of meal, which was a peck a person a week.”

Another historian alludes to “conserve.” This probably was the same kind of blueberry and other wild berry jam for which Massachusetts housewives are still famous.

But most interesting is the fact that there are good grounds for supposing that the Pilgrim fathers and mothers washed their Thanksgiving feast down with “flip” – a species of home-brew livened with a dash of Jamaica rum – a drink that might, nowadays, be termed a “Mayflower Cocktail.”

In spite of the meat and drink, however, the first Thanksgiving Day was no day of great merriment. The hearts of the Pilgrims were too sad. The first winter’s toll in sickness and death had left hardly a heart there untouched.

Priscilla [Mullins], America’s first feminist when it came to speaking of love to John Alden – had lost both her father and mother. The wife Miles Standish married, when Pricilla turned him down, had died [Miles’ first wife Rose]. Edward Winslow, later governor, also had buried his wife [Elizabeth Barker].

One hundred and two persons had landed on Plymouth Rock Dec. 20, 1620. Almost half had succumbed to the hardships, privations, and pestilences of that first year.

Of course, there are various disagreements between historians over the exact date of the first Thanksgiving Day.

Governor [William] Bradford, in his famous “Of Plimoth Plantation,” places it along in July 1631, after a much-needed rain had broken a drought of many weeks. Describing the motive in holding such a day, he says:

“We purpose (the Lord willing) to express in a day of thanks giving to our merciful God (I doubt not but you will consider if it be not fit for you to joyne in it) who, as he hath humbled us by his late correction so he hath lifted us up, by an abundant rejoycing in our deliverance out of so desperate a danger.”

Bradford does not go into detail about the day itself. But he visualizes the pitiful, cowed, and chastened little group of people: “lean, haggard, with ragged clothes, often of insufficient covering.”

Bradford’s date of the first Thanksgiving might be the popular legend now, instead of the 1621 version, had not his history, the only copy, written laboriously by hand, absolutely disappeared at a comparatively early date.

It was found years later, curiously enough, in the library of the Bishop of London, who knew only that it had been there ever since he could remember but had no explanation whatsoever of how it had come there originally.

Another record of a day of thanks that Blanchard mentions in her article was one in 1632, when the Pilgrims rejoiced at the coming of a boat with friends and provisions. They were also expressing gratitude that the colony had gotten rid of a “pest of mosquitoes and rattlesnakes.”

Despite different records of various days of thanks in the early colony, it should be noted that Edward Winslow’s letter to a friend in England has been the most accepted. Written in early December 1621, Winslow described a recent celebration of the fall harvest:

“Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors… amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest King Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain, and others.”

It is primarily because of Winslow’s letter that we celebrate Thanksgiving in late November, a day to celebrate the harvest and to give thanks. Here is a good source on the subject from Smithsonian.

In her article, Blanchard also wrote:

During the Revolution the first suggestion was made that Thanksgiving Day be a national holiday. New York state was the first to adopt an annual Thanksgiving holiday, in 1817.

But not until Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday in November 1864 as a national day of thanks did all the states celebrate the day simultaneously…

Along in the 90s, the late Captain Richard Henry Greene, a man of Mayflower ancestry, conceived the idea of having all Mayflower descendants band together that there might be a nucleus in America to preserve the memory of these illustrious Pilgrim fathers.

With four other men, including Edward Norton and William Milne Grinnell, Captain Greene signed an invitation calling a meeting in 1894 of all New Yorkers who could prove they had Mayflower blood in their veins.

This was the beginning of the present Society of Mayflower Descendants, now a national organization, with headquarters at historic Plymouth, Mass., archives full of records, and a museum of furniture, clothing, and the only authentic original painting of any Pilgrim – that of Edward Winslow. All records of membership are dated Plymouth.

From the beginning of the Society of Mayflower Descendants it has had a certain social prestige. Mrs. Russell Sage was one its earliest members. So were Judge Henry E. Howland, Col. Joseph Slocum, Mr. and Mrs. Edward B. Hill, Augustus Hutchins, Waldo Hutchins, Miss Susan T. Martin, and Victor Seggermann.

By 1896 Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut followed New York’s lead and formed state Societies of Mayflower Descendants. In 1897 the national society was formed.

There are societies now in 19 states in the union, with approximately 6000 members. California, the chapter farthest from the original setting, is one of the strongest and most active…

This society, naturally, is only a small percentage of the descendants of the Mayflower settlers. Historians have figured there must be millions who have a touch of Pilgrim blood, if they could only prove it.

For families, in those pre-Margaret Sanger days, had from nine to fifteen children and those that didn’t die married young and in turn had large families.

John Alden alone, according to one mathematician-historian’s calculations, must have 100,000 descendants! Another prolific line was that of William Brewster. His descendants run almost to six figures, too…

[Some descendants mentioned: William Howard Taft, Charles Evans Hughes, and President Coolidge.] The nation has been led in battle by one member – the late General Leonard Wood. He headed the organization for years and from the Philippines followed its progress eagerly.

Mayflower blood also has done its stint for the American stage. The late Lillian Russell was eligible to this society. Both her sisters belong.

If all the persons belonged who could, there would be almost every nation represented, almost every nationality.

“Tchikawsky” strikes the eyes. A Polish descendant of the Mayflower. There are also Italian names, French names. The descendants are now international.

In the lists are several Irish names which, according to reports, are Catholics, too. And nearby a Jewish name! Apparently Abie’s Irish Rose had its early American version in the first families.

Happy Thanksgiving!!

To be continued…

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial.

Note on the header image: “Thanksgiving at Plymouth,” by Jennie A. Brownscombe, 1925. Credit: National Museum of Women in the Arts; Wikimedia Commons.

Related Article: