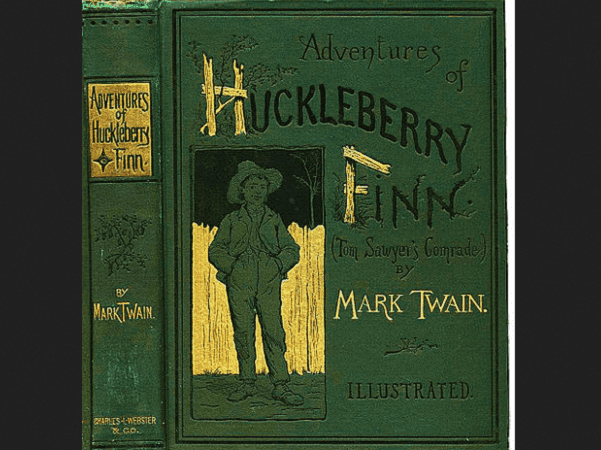

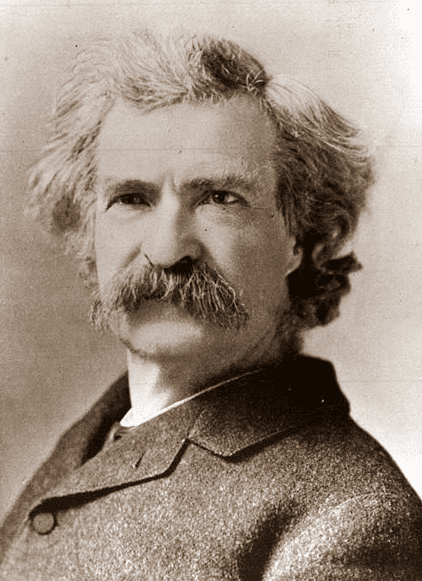

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a novel by Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens), periodically stirs up controversy – as it has since the day it was first published over a hundred years ago. The book is often hailed as an American classic, but some libraries and schools have banned the novel for its perceived crudeness, racial stereotypes, and use of the word “nigger.” This inflammatory word appears more than 200 times in the book, and in reaction some censors have prevented high school students having access to Twain’s novel.

Huckleberry Finn was published in the United States on 18 February 1885 (it was first published in Canada and England, in December 1884, but the American edition was delayed). The novel received generally favorable reviews when first published.

However, the Concord (Mass.) Public Library banned the book when it came out – though not because of the word “nigger.” Instead, the library committee objected to the novel’s “bad grammar” and “rough, ignorant dialect’’ – language used by the book’s characters that Twain worked very hard to capture authentically.

For the most part – Concord aside – Huckleberry Finn was accepted and for 17 years was available in many libraries nationwide. Then, in 1902, the Denver Public Library banned the book for juvenile readers, and a controversy erupted that moved Twain to write the acerbic response printed in the newspaper article below. (Following this article is a second newspaper article about the earlier controversy regarding the Concord library decision.)

By way of background, the “Funston” referred to in Twain’s letter was General Frederick N. Funston, who had given a speech in Denver urging support for the war in the Philippines and suggesting that any Americans who did not support the war effort “should be dragged out of their homes and lynched.”

Twain, who hated the war and America’s imperialistic impulses, published a satirical article, “A Defence of General Funston,” deriding the general and his views. Funston had connections to the Denver Public Library, and Twain was certain the general was involved in the library’s decision to ban Huckleberry Finn. Twain got his revenge the best way he knew how: with his words.

Funston should have realized whom he was tangling with and been more cautious! Surely one of the classic put-down lines of all time is Twain’s caustic remark: “[Funston] is, as usual, a proper object of compassion, and the bowels of my sympathy are moved toward him.”

Twain’s letter was reprinted in newspapers nationwide, and embarrassed the Denver Public Library into quickly lifting its ban on Huckleberry Finn.

Here is a transcription of this article:

MARK TWAIN SCORES MEN WHO DON’T LIKE “HUCK”

The Denver Post, last week on hearing that “Huckleberry Finn” had been thrown out of the Denver Public Library, wired to Mark Twain for an opinion on the subject. Today The Post received the letter herewith printed, but it must add that the efforts of certain individuals to have the book discarded here have failed and “Huckleberry Finn” will again adorn the shelves of the public library as soon as the appropriation will permit its purchase. Mark Twain’s letter is as follows:

Mark Twain’s Letter to the Denver Post.

Your telegram reached me (per post) from “York Village” (which is a short brickbat throw from my house) yesterday afternoon when it was thirty hours old. And yet, in my experience, that was not only abnormally quick work for a telegraph company to do, but abnormally intelligent work for that kind of mummy to be whirling off out of its alleged mind.

Twenty-four hours earlier the Country Club had notified me that a stranger in Portsmouth (a half-hour from here) wished me to come to the club at 7:30 p.m. and call him up and talk upon a matter of business. I said: “Let him take the trolley and come over, if his business is worth the time and the fare to him.” It was doubtless yourself – and not in Portsmouth, but in Denver. I was not thinking much about business at the time, for the reason that a consultation of physicians was appointed for that hour (7:30) at my house to consider if means might be devised to save my wife’s life. At the present writing – Thursday afternoon [Aug. 14] – it is believed that she will recover.

When the watch was relieved an hour ago and I left the sick chamber to take my respite, I began to frame answers to your dispatch, but it was only to entertain myself, for I am aware that I am not privileged to speak freely in this matter, funny as the occasion is and dearly as I should like to laugh at it; and when I can’t speak freely I don’t speak at all.

You see, there are two or three pointers:

First – Huck Finn was turned out of a New England library seventeen years ago – ostensibly on account of his morals; really to curry favor with a personage. There has been no other instance until now.

Second – A few months ago I published an article which threw mud at that pinchbeck hero, Funston, and his extraordinary morals.

Third – Huck’s morals have stood the strain in Denver and in every English, German and French-speaking community in the world – save one – for seventeen years until now.

Fourth – The strain breaks the connection now.

Fifth – In Denver alone.

Sixth – Funston commands there.

Seventh – And has dependants and influence.

When one puts these things together the cat that is in the meal is disclosed – and quite unmistakably.

Said cat consists of a few persons who wish to curry favor with Funston, and whom God has not dealt kindly with in the matter of wisdom.

Everybody in Denver knows this, even the dead people in the cemeteries. It may be that Funston has wit enough to know that these good idiots are adding another howling absurdity to his funny history; it may be that God has charitably spared him that degree of penetration, slight as it is; in any case he is – as usual – a proper object of compassion, and the bowels of my sympathy are moved toward him.

There’s nobody for me to attack in this matter, even with soft and gentle ridicule – and I shouldn’t ever think of using a grown-up weapon in this kind of a nursery. Above all, I couldn’t venture to attack the clergymen whom you mention, for I have their habits and live in the same glass house which they are occupying. I am always reading immoral books on the sly and then selfishly trying to prevent other people from having the same wicked good time.

No, if Satan’s morals and Funston’s are preferable to Huck’s, let Huck’s take a back seat; they can stand any ordinary competition, but not a combination like that. And I’m not going to defend them anyway.

Sincerely yours,

S. L. Clemens

York Harbor, Aug. 14, 1902

Here is a transcription of this article:

“Huckleberry Finn” in Concord.

The sage censors of the Concord Public Library have unanimously reached the conclusion that “Huckleberry Finn” is not the sort of reading matter for the knowledge seekers of a town which boasts the only “summer school of philosophy” in the universe. They have accordingly banished it from the shelves of that institution.

The reasons which moved them to this action are weighty and to the point. One of the Library Committee, while not prepared to hazard the opinion that the book is “absolutely immoral in its tone,” does not hesitate to declare that to him “it seems to contain but very little humor.” Another committeeman perused the volume with great care and discovered that it was “couched in the language of a rough, ignorant dialect” and that “all through its pages there is a systematic use of bad grammar and an employment of inelegant expressions.” The third member voted the book “flippant” and “trash of the veriest sort.” They all united in the verdict that “it deals with a series of experiences that are certainly not elevating,” and voted that it could not be tolerated in the public library.

The committee very considerately explain the mystery of how this unworthy production happened to find its way into the collection under their charge. “Knowing the author’s reputation,” and presumably being familiar with the philosophic pages of “The Innocents Abroad,” “Roughing It,” “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “The Jumping Frog,” &c., they deemed it “totally unnecessary to make a very careful examination of ‘Huckleberry Finn’ before sending it to Concord.” But the learned librarian, probably seizing upon it on its arrival to peruse it with eager zest, “was not particularly pleased with it.” He promptly communicated his feelings to the committee, who at once proceeded to enter upon a critical reading of the suspected volume, with the results that are now laid before the public.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Article: