Introduction: Gena Philibert-Ortega is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.” In this blog article, Gena searches old newspapers to learn about a part of World War II that many people don’t know: there were hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war (POWs) that were kept in the U.S. during the war.

When I was growing up, I – like many youthful book lovers – read the novel Summer of My German Soldier by Bette Green. This fictionalized account dealt with a relationship between an American Jewish girl and an escaped German prisoner from a Prisoner of War (POW) camp in the United States during World War II. This little-remembered history was explored in that book and later the accompanying TV adaptation.

Like many works of fiction, Summer of My German Soldier was loosely based on historical events. During World War II, the United States was home to approximately 400,000 Prisoners of War. Roughly 379,000 were German military personnel. These prisoners were housed in 900 camps scattered throughout the U.S.*

POWs Working and Living in America

For many people, the idea of POW camps on American soil may seem bizarre. This is a part of World War II history not often discussed in high school history classes. During the war, the Allies captured POWs and had to house them somewhere. In many places in the U.S., these prisoners became a part of everyday American life – actually working on individual family farms as well as for larger employers. We associate the idea of prisoners with being locked up and hidden from a community – but not so with the POWs who spent time in the United States during and shortly after WWII. With American men off fighting the war, American women and these POWs helped make up the labor force needed on the home front.

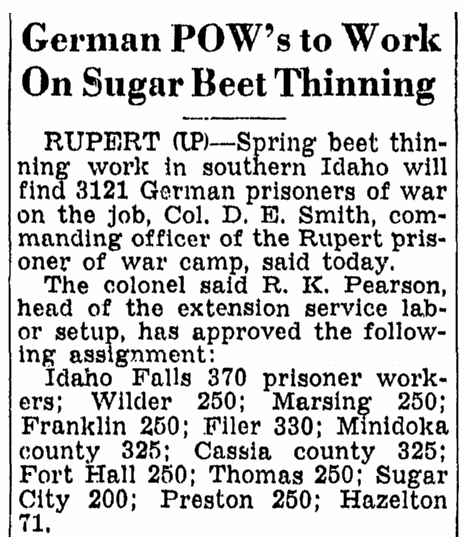

What types of agricultural work did prisoners do? This brief 1946 newspaper article provides one example, reporting on 3,121 German POWs who were assigned to sugar beet thinning in southern Idaho.

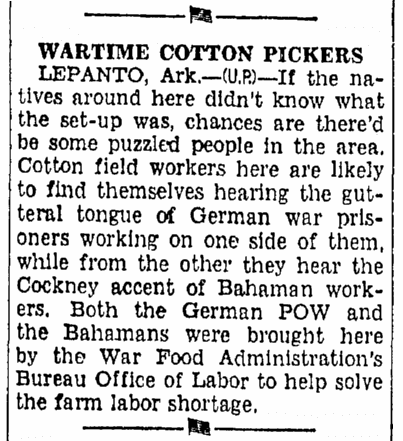

POWs assisted with the shortage of laborers by working on all types of farms. This 1944 article explains that German POWs were brought into Lepanto, Arkansas, by the War Food Administration’s Bureau Office of Labor to pick cotton.

American Resentment for Treatment of German POWs

With the recent release of the movie Unbroken and other similar accounts, we have a better understanding of how our POWs were mistreated at the hands of the Axis powers. So how were enemy soldiers treated in the United States? Prisoners of War housed in America were treated according to the rules of the Geneva Convention. Housing, food and work conditions for POWs were equal to that for our own U.S. soldiers. While this angered some citizens, the Joint Chiefs had hoped that this treatment would be reciprocated for our own POWs held by Germans.** Many Americans considered this fair treatment too good for enemy soldiers. There was much opposition to the perceived “cushy” life that POWs lived in the U.S.

[search_box]

In this letter to the newspaper editor from PFC Robert J. Kuhn, a U.S. soldier and former POW captured in Africa and held in “Italian and German concentration camps,” Kuhn voices his dismay at the preferential treatment of German POWs and their interaction with American women. In his letter, sent from “somewhere in Italy,” he recounts reading in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes about German POWs living in the United States:

…and then I read: “American soldier gets letter from girlfriend now engaged to German soldier – POW from camp in America” – couldn’t believe it. Then I saw in another one: “German prisoners in America have sit-down strike for day.” Also “POW go on excursions in America.” “POW in America have morale dance.”

Did American prisoners of war have German frauleins? Did we go to dances? Did we go on excursions? And above all, did we sit down and strike? No! No! No!

He continues on by mentioning, approvingly, that French women who cavorted with German soldiers had their heads shaved as punishment. His sentiments are understandable, and one can easily see how outrageous it was to American soldiers to find out that enemy soldiers were interacting with American families – and, in some cases, dating American women during their imprisonment!

Some German POWs Escaped

Over 2,000 German POWs tried to escape while being held in the United States. Most POW escapees were caught fairly quickly – but there were a few who eluded capture for months, years, and in at least one case, decades. Many German POW who escaped didn’t get too far before they were caught or voluntarily surrendered.

This 1946 newspaper article tells of the escape of Helmut von der Au (in some articles his name is spelled von Der Aue) from Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky. At the time of the writing of this newspaper article, von der Au had already escaped twice before. He had an advantage over other German POWs who tried to escape from camps in the United States because he could speak English. He had a plan for what he would do in a successful escape: “He would steal a P-38 (Lightning) fighter plane and fly to Greenland.” A lawyer prior to the war, von der Au was apprehended three days after his latest escape when he surrendered to police in Uniontown, Kentucky, less than 10 miles from where he began. He walked up to Police Chief Gilbert Page, still in his prisoner uniform, and asked to be returned to camp because he was hungry.

Helmut von der Au’s story doesn’t end there. He eventually is sent to Mississippi where he is one of many prisoners who helps out on a plantation. Over time he becomes well acquainted with the plantation owner’s wife and the two fall in love. Running off together seemed like a good idea at the time, but the couple is eventually caught and his American lover, Mrs. Edith Rogers, was held for aiding in the escape of an enemy of the United States.

According to this 1946 newspaper article, the “…27-year-old, dashing German officer met Mrs. Rogers, 37-year-old Mississippi society woman, as a member of a war prisoner labor detail assigned to the 1000-acre Bolivar county plantation of her husband, Joseph R. Rogers. He and Mrs. Rogers became such close friends, von Der Aue explained to federal authorities…that after a number of drinks they decided to leave and be married.”

Edith Rogers wasn’t the only American woman to fall in love with a German POW. Joan McBride, with the help of her husband James McBride, assisted Rudolph Joseph Soelch, a former bodyguard for Hermann Goering, escape from the camp he was being held at in Southern California. For six months Soelch lived as “Mr. McBride” and worked in Detroit alongside Joan. Joan’s husband left her when she proclaimed her love for the German POW. Eventually they were apprehended and Soelch was repatriated back to Germany and told never to enter the United States again.

Repatriation of POWS after the End of WWII

World War II came to a close with Japan’s surrender on 2 September 1945. Now the work of repatriation of all POWs living in the United States would begin.

[search_box]

January 1946 newspapers announced that former Axis soldiers would be sent back to their home countries in four months. (In reality it took longer.) The newspaper article below explains that later that month Japanese POWs would be sent out of the U.S. mainland but would not go directly home. Some would be sent to Hawaii for assignments. The historical news article ends by asserting that some POWs did not want to go home. Understandably, due to high unemployment and conditions in their homeland, some German POWs wanted to stay in the United States.

While there were German POWs who eventually returned to the United States to live permanently, there were undoubtedly some cases where they wanted to return as soon as possible – like in the case described in this 1946 newspaper article, where a young POW stowed away on a ship so that he could return to the United States because “he liked it so much.”

World War II History and Family History

As family historians, we seek to learn more about our family’s lives. As you research your military family and ancestors, don’t forget about those on the home front. I’ve had family members tell me stories of living near POW camps and the experiences they had living in close proximity and interacting with the “enemy.” Now’s the time to seek out these remembrances, or to record your own.

To learn more about World War II history on the American home front, check out GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives.

In addition to the news reports and first-hand accounts that can be found in old newspapers, several books have been written about POW camps in the United States. They include:

- Buck, Anita. Behind Barbed Wire: German Prisoners of War Camps in Minnesota. St. Cloud, Minn: North Star Press of St. Cloud, 1998.

- Fiedler, David. The Enemy among Us: POWs in Missouri during World War II. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2003.

- Krammer, Arnold. Nazi Prisoners of War in America. Chelsea, MI: Scarborough House, 1996.

- Marsh, Melissa A. Nebraska POW Camps: A History of World War II Prisoners in the Heartland. Charleston: The History Press, 2014.

Did you or any of your family members have any contact with POWs held in America during WWII? Please tell us your stories in the comments section.

———————

* HistoryNet. German POWs: Enemies In Our Midst. http://www.historynet.com/german-pows-enemies-in-our-midst.htm. Accessed 17 February 2015. This resource includes a map with POW camp locations.

** HistoryNet. German POWs: Coming Soon to a Town Near You. http://www.historynet.com/german-pows-coming-soon-to-a-town-near-you.htm. Accessed 17 February 2015.

[bottom_post_ad]