Many people think the Civil War ended when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865. However, Lee was in charge of only one army, the Army of Northern Virginia. The South had several other armies, and they surrendered one by one throughout April and May.

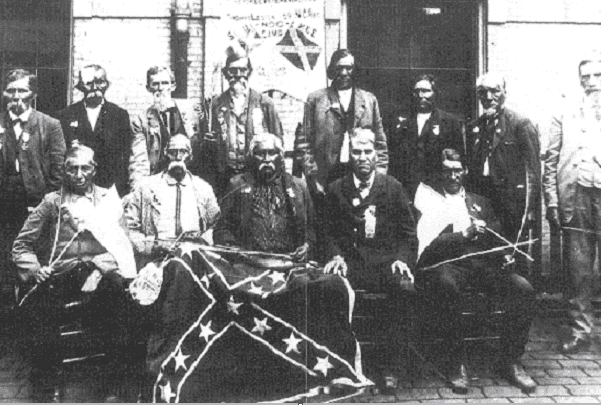

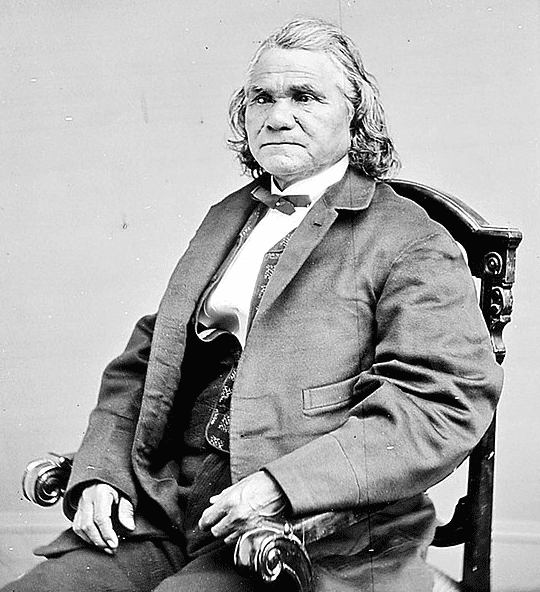

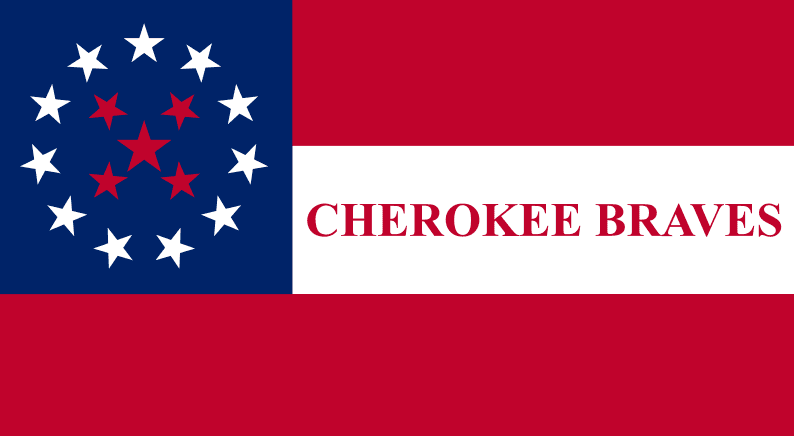

Surprisingly, the last Confederate army to surrender in the Civil War was not made up of Southern whites: it was the Cherokee army of Brigadier General/Chief Stand Watie, whose troops gave up the fight on 23 June 1865, at Fort Towson in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

The following newspaper article describes this final surrender of Confederate forces, with the reporter noting warily that “We hope and we fear. The wild Indians are hard to manage; the educated, or those considered such, not always trustworthy.”

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Treaty with the Choctaws and Cherokees.

[From the Leavenworth Bulletin.]

That is an important treaty made with the Indians on our border, and if the letters from Fort Smith are to be relied upon, it is made and will be kept in good faith.

The stipulations were entered into and agreed upon June 23, 1865, between United States Commissioners and General Stand Watie, representing the rebel Indians. These stipulations are:

ARTICLE 1. All acts of hostility on the part of both armies having ceased by virtue of a convention entered into on the 26th day of May, 1865, between Maj. Gen. E. R. S. Canby, United States Army, commanding Military Division of the Mississippi, and Gen. E. Kirby Smith, Confederate States Army, commanding Trans-Mississippi Department, all the Indians of the Cherokee Nation here represented, and who were lately allied with the Confederate States in acts of hostility against the Government of the United States, do agree with as little delay as possible to return to their respective homes, and there remain at peace with the United States, and offer no indignity whatever, nor commit any act of hostility against the whites and the Indians of the various tribes who have been friendly to or engaged in the service of the United States during the war.

ART. 2. It is stipulated by the undersigned commissioners on the part of the United States, that as long as the Indians aforesaid observe Article 1 of this agreement, they shall be protected by the United States authorities in their persons and property, not only from encroachments on the part of the whites, but also from the Indians who have been engaged in the service of the United States.

ART. 3. The above articles of agreement to remain and be in full force and effect until the meeting of the Grand Council, to meet at Armstrong’s Academy, Choctaw Nation, on the first of September, A. D. 1865, and until such time as the proceedings of said Grand Council shall be ratified before the proper authorities, both of the Cherokee Nation and the United States.

In testimony whereof, the said Lieut.-Col. A. C. Matthews and Adjt. Wm. H. Vance, Commissioners on the part of the Unites States, and Brig.-Gen. Stand Watie, Governor and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, hereunto set their hands and seals.

A. C. Matthews, Lieut.-Colonel.

Wm. H. Vance, Lieut. and Adjt. U.S. Vols.

Stand Watie, Brig.-Gen. and Principal Chief.

Gen. Watie gave the Commissioners every assurance, and so did Gov. Pitchlynn, of the Choctaws, and Lieut. Porter, of the Creeks, who was a delegate to the Grand Council at Armstrong’s Academy, that any agreement entered into by Gen. Stand Watie on behalf of the aforesaid tribes, would be respected by them.

The resolutions adopted by the council at Armstrong’s Academy provided for sending commissioners to Washington to negotiate a treaty of peace with the United States. They provide that each tribe should send delegates, and empowered them to effect a treaty, separate for each tribe or nation, after which each and all of the treaties to be submitted to the councils of the respective nations for ratification. At the time the council was held at which the resolutions referred to were adopted, the delegates were not officially notified of the surrender. Yet they were aware that negotiations were pending, and anticipated the result; but, knowing what would be the character of the surrender, provided for sending delegates to Washington.

After the arrival of the commissioners in the territory, the authorities of the tribes with whom the commissioners conferred asked that a council be called to meet on the first of September next, which would supersede the necessity of sending commissioners to Washington.

We hope and we fear. The wild Indians are hard to manage; the educated, or those considered such, not always trustworthy. Yet, as they have been subdued; as the Creeks have felt once the power of the nation (the Choctaws have been friendly to the whites), we may expect peace. The rebel Indian leaders proposed, for this end, first, a settlement of Indian difficulties among themselves; second, a grand council for this end; and in accordance with this policy, the governor and principal chief of the Choctaw nation, P. P. Pitchlynn, has issued a proclamation, calling the aforesaid council of all the Indians of the Indian confederation and the Indians of the prairies, to be commenced and held on the first day of September, A. D. 1865, at Armstrong’s Academy, in the Choctaw nation, at which time and place there will be duly authorized commissioners from the United States to treat on the subject of a permanent and lasting peace.

If we understand the report of the United States Commissioners, they have faith in the result. The assurances of the chiefs are certainly very strong. The wild Indians say “mark out the path, we will follow”; the civilized agree to commit no acts of hostility against the Government of the United States, nor to molest the whites in any way whatever, and to allow emigrants, the overland mail, &c., to pass through the territory unmolested.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Article: