Irish Americans proudly display their heritage in their last names. The Kelly’s, the Murphy’s, the O’Connor’s and the Byrne’s – such names bring to mind the clans of old, the heady days of warring kerns and heroic galloglaighs. But where did these names come from? What is the story behind the Irish surnames that so many Americans carry to this day?

First Names First

Before understanding Irish last names, it is essential to remember that first names have meanings all their own. For example, look at the Irish surname O’Brian. The O has a meaning that we will cover below, but what about the Brian part? Such commonly used names should not be taken for granted, because they provide a key to our ancestors. Somewhere down the O’Brian genealogy line was the original Brian, himself. No O. Just Brian. The same goes for the original Donnell of the MacDonnells and the first Allen of the McAllens. The descendants of Brian (meaning “noble”), of Donnell (meaning “world-mighty”), and Allen (meaning “handsome”) remember that somewhere down the line their ancestor earned or was given that name.

The O’s, the Mac’s, the Mc’s and the Fitz

In the old country, in the days of yore, a person was not so much defined by who they were but by where they came from, who their father was, or their trade. The uppermost heights that a son could gain were the same as those of his father or grandfather.

The Mc in “McDonnell” and the Mac in “MacDonough” all mean “son of” in the native Gaelic, and all have survived and flourished as common prefixes to Irish surnames (though the original Mac is more common in Scotland). The feminine form, nic (meaning “daughter of”) is a rarity in modern Irish last names, which reflects the patriarchal society.

Son of…

Patrick, son of Brian, or Patrick mac Brian, was the given formula for how Irishmen would first describe themselves in the Middle Ages. In the meantime, Brian, the father of Patrick, would be known as Brian mac Connor, or the son of his own father, Connor. Mac – sometimes shortened to Mc – was said after the man’s given name and before the name of his father, denoting his male parentage. This method generally told enough of an Irishman’s story to identify him from others.

Unlike in modern times, where surnames are very much essential to our identity in day-to-day life, the early Irish rarely needed to use them. The fact was, in an isolated, tribal society (known as “tuaths”) where everyone came from the same place and very little family history was recordable, it just made more sense to say who your father was rather than give your ancestral line. Thus, Patrick, Brian, and Connor would all have different surnames (surnames meaning: sired by) as each of their fathers would probably have a different given name (though names such as “Patrick mac Patrick” did occur, i.e., junior).

Due to this generational change from one surname to another, it is difficult to trace Irish last names into the medieval period. However, like society itself, the tradition of Irish last names changed with the times. Feudalism, Catholicism, foreign invasions and intertribal wars brought pride in one’s lineage very much into vogue. Having an ancestor who was a landed lord, being the descendant of a saint, or someone in the line of ancient kings became incredibly important to the upper classes of medieval Irish society.

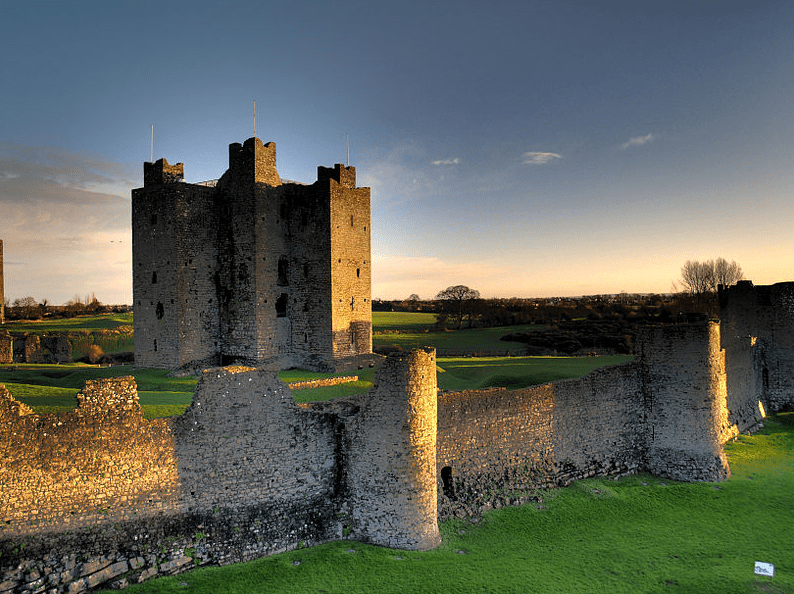

The First Irish Surname

The first Irishman with a recorded last name, Tigherneach Ua Cleirigh, was a lord who died in 916 C.E. in what is now modern-day Galway. The Ua denotes Tigherneach as being either the “son of,” “grandson of,” or “descendant of” Cleirigh (modern: Clery). The Ua would later become the O we are all familiar with in such names as O’Connell or O’Leary. This change to “grandson of” or “descendant of” is an important departure from simply saying “son of,” as it alters the narrative of a person’s name from “this is my dad” to “this is my family.” The most widely seen example of this comes from the name O’Brian, denoting a descendant of the legendary King Brian Boru… or giving a coincidental bit of luster to those with a different ancestor named Brian.

The Fitz

It would be the feudal lords and barons that first took on the mantle of Irish surnames to denote their familial lineage, and no one brought the hammer of feudalism quite like the Normans. In 1169 C.E. they invaded Ireland in a stunning sequel to their invasion of England in 1066, bringing with them their particular blend of oppression and progress. To say it was a rough go for anyone under the Norman boot is an understatement, but it is also how Irish surnames gained the prefix Fitz, as in Fitzpatrick. This Latinized form of “son of” is still a popular prefix found in Irish last names. Not only that, but the Normans – and, more so, their English successors – altered the “son of” formula that had heretofore been the most common source of surnames in Ireland.

Irish Occupational Surnames

“Smith” is an incredibly common name in the English-speaking world. But who was this Smith? What did he or she do that was so magnificent to have so many modern ancestors still proudly bearing their namesake? Well, in a word: they smithed. They were blacksmiths, locksmiths, gunsmiths, goldsmiths, etc. In medieval England what a person did, or what their family business was, often determined their last name. This is why there are still so many Archers, Cooks, Coopers, Masons, Thatchers, Fishers, Butlers, and Wrights in England and, since the English occupation, in Ireland.

Such occupational surnames were fairly common in the early Irish lexicon, especially considering that specialized occupations were commonly passed down from parent to child. Irish surnames like O’Leary (from Ó Laoghaire, meaning calf-herder) or McLoughlin (from Mac Lochlainn, meaning Viking) tell the tale of sons who followed in the footsteps of their fathers. In fact, it wasn’t until the Normans and English established their feudal fiefdoms on the island and the markets and cities began to grow, that such names began to become invaluable. These last names immediately told a lord or merchant what you did and how you could help them. Think of them as business cards built into a name, an effective and subtle marketing tactic that a journeyman worker or skilled artisan would have been a fool to pass up.

Irish Toponymic Surnames

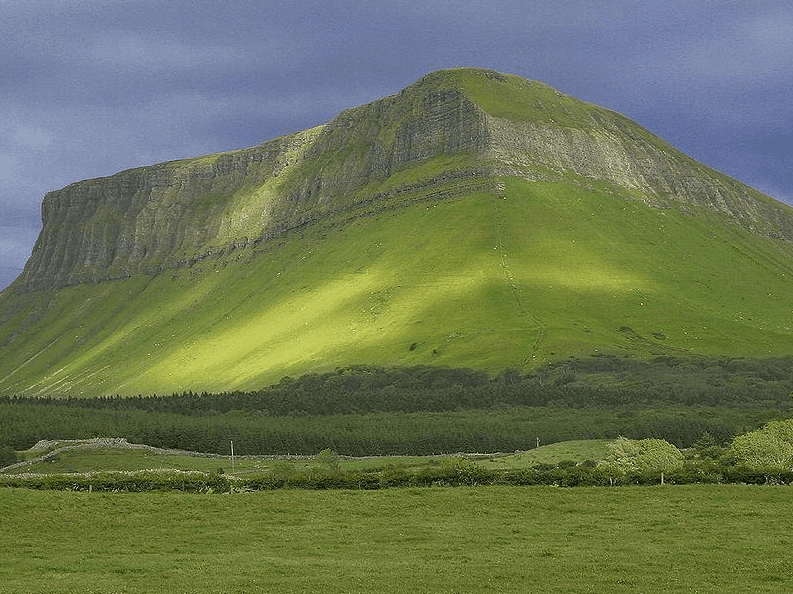

Trade brought toponymic last names to Ireland. Brian of Bray would become Brian Bray, while William from Wales became William Walsh. Barring a few examples, these names are not typical in Ireland, as strangers in a strange land – especially in less than tolerant times – are more inclined to assimilate rather than celebrate their differences. However, this is not the case with those who conquered…

Anglicization: How Irish Last Names Changed

By the 1500s, traditional Irish Catholicism was put down in favor of English Protestantism and much of the native Irish population was resigned to second-class citizenship. This forced the Irish to Anglicize, to adapt and become more like their conquerors in order to survive these times. This is why so many Irish names have evolved beyond their Gaelic origins to fit more easily into the English language, some dropping the classic prefixes while others translated completely. Thus, Ó Ceallaigh became Kelly, Ó Murchadha became Murphy, while Mac Gabhann (the Irish occupational last name for a smith) became Smith.

The traditional Gaelic names changed under English rule. Anglicization became a way of survival for many Irish people during the last five centuries and resulted in the Irish surnames we all know today.

10 Common Irish Last Names & Their Meanings

Below are some of the most common Irish last names not discussed above. Our family history research is often guided by our surnames. Find your Irish last name in the list below or use our surname meaning search to find your name and learn more about your Irish heritage.

- Byrne: meaning “raven,” the name is the seventh most popular in Ireland while the historic Byrne’s are notable for their resistance to foreign invaders.

- Doyle: anglicized from Ó Dubhghaill, meaning “dark-haired foreigner,” Doyle was originally a term for the Danish Vikings who settled in Ireland in the early Middle Ages. The term was meant to differentiate them from the Norwegian Vikings, the Fionnghoill, or “fair-haired foreigners.”

- Kelly: meaning “bright-haired” or “red-haired,” the last name Kelly is practically synonymous with Irishness, possibly due to the widely popular folk song “Kelly the Boy from Killane.”

- Kennedy: the Irish surname made famous by J.F.K., Bobby, and their new American Camelot, Kennedy means “helmeted-head” in Gaelic. Despite its modern connotations of political royalty, the name is one of the most common in Ireland.

- McCarthy: from Mac Carthaigh meaning “loving person,” the most widely known Carthaigh was a contemporary of the legendary king Brian Boru and one of his main rivals.

- Murphy: the most common Irish surname deriving from the Gaelic MacMurchadh, meaning “sea-battler,” Murphy’s around the world owe their name to the notorious Irish sailors who raided the British coast before the Viking Age.

- O’Connor: in Gaelic, Ó Conchobhair was a term that meant “patron of warriors.” The eponymous Conchobhair was the first king of Connaught, a county of Ireland that still bears his namesake.

- O’Reilly: from the original Ó Raghallaigh meaning “extroverted one.” The historic O’Reilly’s are one of the most storied families in Ireland, even minting their own coins in the 15th century leading to the still-in-use Irish slang term “Reilly” to denote high value.

- O’Sullivan: from the Gaelic Ó Súilleabháin, Sullivan has a variety of meanings, all to do with the eye. Some believe it means “dark-eyed,” while other theories suggest “one-eyed” or “hawkeyed.”

- Ryan: combining the Gaelic words for little (an) and king (ri), Ryan simply means “little king.” Whether this was meant as a term of endearment or a good-natured insult is up for debate, though the name’s other translation, “illustrious,” would sway most to the former theory.

Who we are and where we came from can help us find out where we’re going. Newspapers hold the key to helping you uncover new details about your Irish ancestors’ lives, their trials and tribulations, and your family history. Search our collection of Irish newspapers published in the U.S. to trace your Irish ancestry.