I have always known that my ancestor William Kemp was a very religious Methodist – so much so that he built and started a separate Methodist Church on an empty lot on his street.

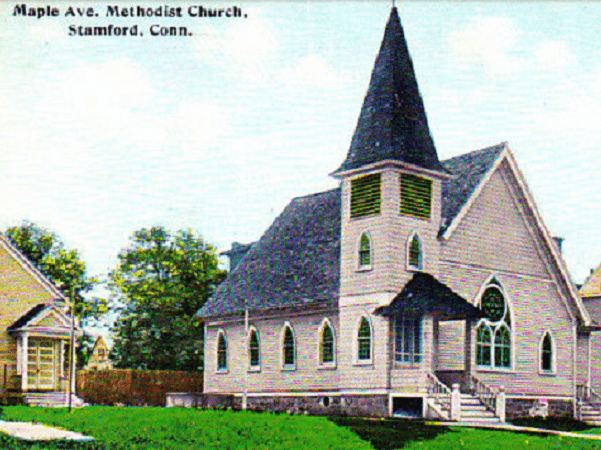

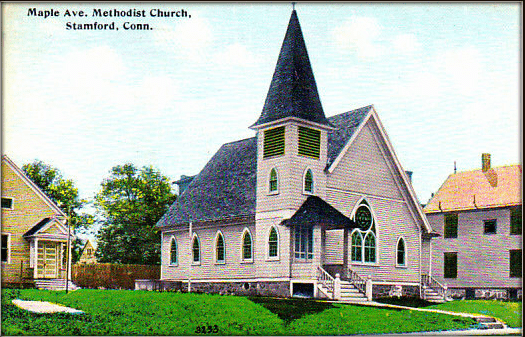

The Maple Avenue Methodist Church was located at 68 Maple Avenue, Stamford, Connecticut. William owned property up and down Maple Avenue. His home was across the street from the church, and his son John lived a few houses down at 58 Maple Avenue.

At that time, William’s church was listed as a “Primitive Methodist Church” – a specific denomination that still exists today.

Along with their distinctive name, they have a comfortable sense of their focus – and, with a touch of good humor, they use this logo on their denominational Facebook page.

While Primitive Methodism’s roots are in England, it started in the United States in the 1840s – and it was not an easy launch.

In the late 1890s, the Stamford Methodist Church was the largest Methodist congregation in America. So, what happened there was visible to the entire church. Clearly there was an internal struggle among Methodists in accepting the “Primitive Methodist” approach.

The website Jesus Army – an evangelical Christian site with a “charismatic emphasis” that sees the “Shouting Methodists” as part of their larger historical background – writes this about the denomination:

“Some early Methodists were known for their noise… One name commonly applied to early nineteenth century Methodists was ‘shouting Methodists’ – a name Methodists were glad to accept and make their own. What was meant by the term, ‘shouting Methodists’?

“At the very least, it meant that Methodists were a noisy lot, interrupting the preacher with ejaculations of ‘Praise the Lord,’ ‘Hallelujah,’ and ‘Amen.’ Alexander Campbell declared that the Methodist church could not live without her cries of ‘Glory! Glory! Glory!’ And he reported that ‘her periodical Amens dispossess demons, storm heaven, shut the gates of hell, and drive Satan from the camp.’

“It is clear that ‘shout’ was a prominent part of the Methodist vocabulary. Nowhere is this more evident than in the refrains of their spiritual songs. ‘Shout, shout, we’re gaining ground,’ they sang. ‘We’ll shout old Satan’s kingdom down.’ The word would appear in casual conversations. An aged person, for example, would rejoice at being still able ‘to shout,’ and a death would be recorded: ‘She went off shouting.’

“What did it mean to ‘shout’? ‘Shouting’ was never mere noise. ‘Shouting’ was neither preaching nor exhorting. Exhorting was a noisy performance, but the word had a technical meaning that was not broad enough to include even the ‘action sermon.’ Nor was ‘shouting’ praying, not even when praying became a din as a congregation sought to ‘pray down’ a sinner or to contend in prayer for the souls of the penitent.

“The term ‘shouting’ suggests confusion, and this was the initial impression one gained of Methodist meetings. Devereux Jarratt, a Methodist himself prior to the separation of 1784, reported of a Methodist gathering in 1776 that ‘the assembly appeared to be all in confusion, and must seem to one at a little distance more like a drunken rabble than the worshippers of God.’ The development of a specialised vocabulary with highly technical meanings, on the other hand, suggests that there were patterns of group activity in the midst of the confusion, a degree of order and method in the apparent madness.”

I turned to GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives to learn more of the story.

Clearly my ancestor William Kemp held to this “Shouting Methodist” tradition. The newspapers recorded that on multiple occasions he would stand up during the Sunday services “interrupting the preacher with ejaculations of ‘Praise the Lord,’ ‘Hallelujah,’ and ‘Amen.’

As the Boston Daily Advertiser described:

“[William Kemp] belonged to a [Sunday School] class… that was very noisy… Such was the state of affairs about 3 yrs. ago when the present pastor, Rev. F. W. Crowder, entered upon his duties here. The situation did not better itself any under the new pastor.”

The Rev. Frank W. Crowder clearly did not support the growing “Shouting Methodist” faction in the congregation. During the three years he was the pastor there he tried to deal with the situation. He devised a plan to decide who could and couldn’t attend Sunday School and announced his plan prohibiting the “Shouting Methodist” faction from the class – and that “only served to bring things to a crisis.”

According to that same 1899 Boston Daily Advertiser article:

“On Oct. 13 [William Kemp] appeared at the church and demanded that he be allowed to take part in the [Sunday School] class. He refused to leave the church, and finally the pastor called in a policeman and had him put out.”

Wow – the minister had the police eject William from the church meetings.

Following this, Rev. Crowder put William Kemp on “trial” for his theological position.

It was a frontpage story not only in Stamford, Connecticut, but also in New Haven. What was at issue was the evangelical, charismatic “Holiness” movement approach within the Methodist Church.

William lost and the controversy continued. By February 1900 the minister announced he was going to put another church member, Charles Swenson, on trial for his faith.

Charles Swenson resigned from the church instead of facing a church trial – and importantly, he was “a contractor.”

We know what happened next for William, Charles and their “Shouting Methodist” co-religionists. They left the main Stamford Methodist Church, then organized and built the Maple Avenue Methodist Church where they and their descendants worshipped for decades after that.

But, what happened to the Rev. Crowder?

Within weeks of this episode, the Rev. Crowder resigned as a Methodist minister.

He opted instead to leave Methodism and became an Episcopalian. He was ordained as an Episcopalian priest and moved from Stamford, Connecticut, to New York City to continue his career in a different denomination.

Thanks to the old newspapers in GenealogyBank, I have more details on the rest of the story. GenealogyBank includes digital copies of every page of each issue of America’s newspapers from 1690 down to today. Rely on it to find and document the details of your ancestors’ lives.