Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega searches old newspapers to learn more about the mysterious disappearance of pioneering woman pilot Amelia Earhart, who vanished seemingly without a trace on 2 July 1937 somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

Everyone knows about her. The life of Amelia Earhart is legend. The early aviatrix’s love of flying started with her first plane ride in 1920, and continued through flight lessons in 1921 and her role as the first female member of a flight crew to cross the Atlantic in a plane, in 1928.

Her life was full of firsts, but she wanted more: more challenges, more new or broken records, more flying. Her attempt in 1937 to be the first woman to fly around the world would prove to be her last – but that one singular attempt has captivated everyone’s imagination for 80 years, due to her mysterious and still unexplained disappearance.

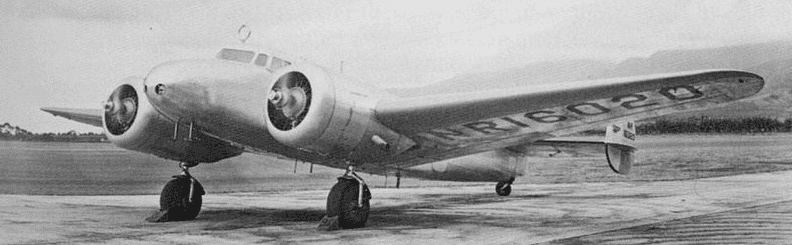

In 1937, 29,000 miles seemed like a good challenge for the 39-year-old aviatrix, who was joined on her attempted record-setting flight by navigator Fred Noonan. They were flying a specially-modified Lockheed Electra 10-E airplane built to Earhart’s specifications. Her first attempt at the record had to be scrapped due to mechanical problems, but she nearly made it on her second try.

That second attempt saw her take a route from west to east, flying 22,000 miles with stops in South America, Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, and Southeast Asia. On 29 June 1937, she landed in New Guinea. She had 7,000 miles to go – but those remaining miles were all over the Pacific Ocean.*

Disaster Strikes

On July 2nd Earhart and Noonan departed Lae, New Guinea, en route to Howland Island. Despite some inclement weather, Earhart and Noonan appeared to be getting close to the small island where they wanted to land. At 6:14 a.m. she radioed the USCGC Itasca stationed at Howland Island to say she estimated she was 200 miles away. Then at 6:45 a.m. she reported she was just 100 miles from Howland Island.

At 7:42 a.m., the Itasca picked up a message: “We must be on you, but we cannot see you. Fuel is running low. Been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.” At 8:43 a.m. Earhart made what is believed to be her last radio transmission when she said: “We are running on line north and south.”** Not only was Earhart losing radio contact with the Itasca, her plane was running out of gas.

She was never heard from again, and no wreckage from her plane has ever been found.

As soon as the news broke of Earhart’s disappearance, newspapers wasted no time publishing articles detailing everything known about the missing plane and her crew. Articles blanketed multiple pages of daily newspapers reporting everything from interviews with friends and family of Earhart and Noonan, to facts about her plane and the flight plan, to the rescue attempts.

In addition to a front page article, the 3 July 1937 issue of the Seattle Daily Times had two pages devoted to articles about Earhart, Noonan, and the search. As you can imagine, great hope existed in those first few days after Earhart’s plane disappeared.

While official channels were monitoring the radio transmission of Earhart, so too were amateur radio enthusiasts. The article “Navy Plane Speeding to Aid Search at Howland” mentions that on the day of her disappearance, in addition to the Coast Guard and Pan American Airways, amateur radio operators were following Earhart’s radio. This was a rescue effort that many, both government and civilians, felt a part of.

There was hope in those first hours and days after the disappearance. Maybe she landed the plane on a neighboring island or was floating in the ocean (or Earhart and Noonan were aboard the inflatable boat they carried with them). Earhart’s husband, the publisher George Palmer Putnam, remarked: “The plane should float, but I couldn’t estimate for how long because a Lockheed plane has never been forced down at sea before.” Earhart had other emergency supplies with her including life belts, flares, signal kit, and food and water.

As those early newspapers articles speculated as to where Earhart was, civilians had their own theories. Charles Randolph, Jr., a 12-year-old boy from Wyoming, reported picking up a faint radio transmission that said “Amelia Earhart calling… ship on reef south of the equator” on the morning of 5 July 1937. The newspaper Times-Picayune reported that an air official said the report was “plausible and not improbable.” That boy’s report of hearing Earhart’s faint voice over the radio waves was one of many that were most likely not Earhart, but instead wishful thinking.

The Search

The Coast Guard cutter Itasca, in charge of providing radio and air navigation support, started the initial search for Earhart’s plane. However, by the afternoon of July 3rd it reported that it had scanned 3,000 square miles of ocean and had not seen any sign of the aviatrix, her navigator, or their plane. Help was on its way to increase the search, including the aircraft carrier Lexington, which was sent from San Diego, California.

The search continued for two weeks, but no matter how many soldiers, ships, and planes scanned the ocean and nearby islands, nothing was found and hope changed to dread. On July 16th, the newspaper reports mirror the loss of hope of those who were searching in vain.

For example, the following Times-Picayune article starts out commenting on the 1500 “sweltering sailors” laboring on the search and explains that “Forty-two planes again left the decks of the aircraft-carrier Lexington for their third sweep of the equatorial seas about Howland Island. Three and one-half hours later the air fleet returned, empty-handed as usual, to the Lexington.”

After spending 17 days searching over 250,000 square miles of ocean, on July 19th the search was declared over.*** The San Francisco Chronicle’s front page declared “Navy Gives Up Its Hunt for Amelia.” Admiral Orrin G. Murfin, commander of the Fourteenth Naval district, reported that:

“We have covered all possible territory… some of it we have been over as much as three times. I could not conceive of any other place where we might direct our search, and obviously we can’t keep it up indefinitely. We feel that we’ve done everything possible now.”

A search that included the Itasca, the mine sweeper Swan, the USS Lexington, and 62 of its planes was over. Amelia Earhart and her navigator Frederick Noonan were considered dead.

The Mystery Continues

The mystery of what happened on 2 July 1937 still intrigues those who love history, and Amelia Earhart’s many fans. Numerous books and research trips are part of the continuing efforts to try to answer the question of what really happened that July morning. Did Earhart and Noonan drown in their plane that plunged to the ocean floor, or did she land on a neighboring island waiting for the rescue that would never materialize? Was she captured by the Japanese who executed her for being a spy?

Like most lovers of history, I hope that one day we learn the truth about what happened to Amelia – but I also believe it’s important to remember her for more than just her disappearance. Ultimately, Amelia Earhart wanted to show the world that women were the equals of men.

Before her 1928 Atlantic flight she wrote:

“I have tried to play for a large stake. If I succeed, all will be well. If I don’t I shall be only too happy to bop off in the midst of such an adventure.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

———————–

* “Amelia Earhart,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amelia_Earhart: accessed 5 July 2017).

** “Biography,” Amelia Earhart (http://ameliaearhart.com/biography/: accessed 5 July 2017).

*** Ibid.

Related Article: