Introduction: In this article, Katie Rebecca Garner gives tips for finding and using an important resource for genealogy: obituaries. Katie specializes in U.S. research for family history, enjoys writing and researching, and is developing curricula for teaching children genealogy.

Genealogists spend a lot of time searching for – and then studying – death records. This pursuit may seem morbid to non-genealogists, but family historians know the important information death records can provide about your ancestors. To go beyond vital statistics and learn more about the actual stories of your ancestor’s life, the best death record of all is often an obituary.

About Obituaries

The oldest obituaries date back to ancient Rome and were written on papyrus newspapers called Acta Diurna (“Daily Events”). Printed newspapers became common after the invention of the printing press, but the publication of obituaries in newspapers wasn’t common until the nineteenth century. Prior to the invention of the Linotype machine, printing newspapers was a more laborious process – so newspapers were short, and therefore obituaries or death notices were brief.

Early death notices were submitted by the funeral homes and contained little information compared to relatively recent obituaries. A death notice usually contains: the name of the deceased and date of death; age or birth information may be mentioned; living relatives may be mentioned. For funeral announcements, the date and place of the funeral would be mentioned. In the case of a deceased child, a few lines of poetry might be included.

Eventually, as more attention was paid to death notices in newspapers, they began to serve as a place for public expression of mourning. Another motive for publishing obituaries was to publicly let creditors know of the death.

Use of obituaries expanded after the turn of the twentieth century with advances in printing technology. Since newspapers charged a fee for publishing obituaries, this was a way for publishers to make money. By the 1930s and 1940s, obituaries included a short bio and listed surviving relatives. By this time, shorter obituaries were being written by family members and longer obituaries were being written by staff journalists. This was also the beginning of the modern trend of including a photo of the deceased in the obituary.

After 9/11, the New York Times published short narrative obituaries of each person killed in the attack. This started a trend of more detailed and open obituaries. Suicides, addictions, and other skeletons in the closet, which were previously kept hidden, began being mentioned in obituaries. Today, obituaries are published online and posted on social media.

Case Study: Three Obituaries

Three extraordinary death notices were published back-to-back in the Pennsylvania Telegraph on 21 October 1846. Pennsylvania was not good at keeping vital records in the nineteenth century, so it’s possible these newspaper clippings are the only records of these deaths.

Genealogists researching these families would no doubt know more about these people from other records. Unless these genealogists have other evidence that these people died around this time, these obituaries would provide the researchers with the death dates and places of the persons in question. Even if they know when they died, these notices provide interesting stories around the deaths.

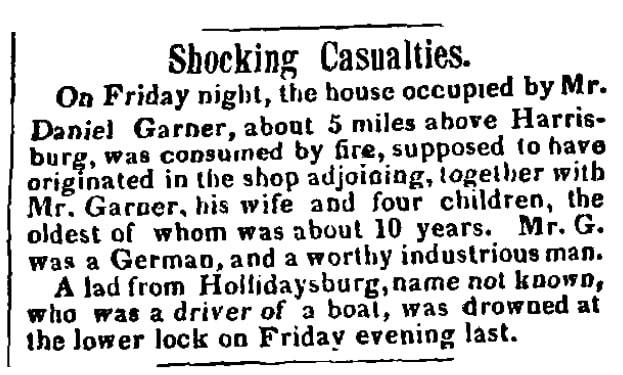

This first obituary, “Shocking Casualties,” describes two deadly incidents – by fire and water, ironically.

Daniel Garner and his family died the prior Friday, 16 October 1846. His wife and children are not named, but the demographics given could be helpful in identifying the family on other records. The mention of Daniel Garner being a German suggests that immigration research could be conducted on him. If there’s any clue that Daniel Garner owned his land, there would have been a probate process after his death which might identify other relatives.

The other death mentioned in the same article doesn’t name the person who drowned, so the genealogical value is limited. The occupation and residence are mentioned. This death also occurred on Friday the 16th. (So much for Friday the 13th being unlucky.)

This next notice details murders that were previously published in the Lancaster Union and Tribune Extra. Before social media, things went viral by being republished in other newspapers. The editor of the Pennsylvania Telegraph evidently thought this piece of news from Lancaster was important enough to be republished.

Not a lot of genealogically valuable information about the murdered family is given, as only the father is named. This article gives a graphic story of the dramatic cause of death, which is not information you can easily find for many ancestors.

Since Haggerty was arrested and imprisoned for the murders, there is a high chance that court records exist for this case. If the families of the murdered victims or the murderer had any involvement in the case, they may be mentioned in the court records. Whether or not there’s mention of relatives, the court records likely have more detail on the murder than the newspaper clipping.

The surviving, orphaned Fordney boy would likely have been sent to live with other relatives, and there would likely be guardianship records reflecting this. The first census this boy would be named on is the 1850 census, where he would be living with the relatives who took him in. A researcher who knows details of his later life would have troubles tracing the line back without the information in this death notice.

This next obituary, “Melancholy Casualty,” appears to be another article that went viral the old-fashioned way.

This one came from the Lewistown Gazette, which published it on 17 October 1846. The apparent date of death is 9 October 1846. This article details how three young women went to secure items from flooding, only to drown in said flood. The ladies were all mentioned by surname only; the other named person is Jacob Ort. The families of these girls and Jacob Ort likely all knew each other, which is a good clue for FAN club research.

These three articles not only give the dates and places of death, but also have dramatic stories associated with the deaths. Obituaries you find of your ancestors may contain similarly valuable information and give clues to further research.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records – including more than 260 million obituaries – in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial.

Related Article:

Resources: