Introduction: In this article – in honor of today being Constitution Day – Jane Hampton Cook tells the story of how 55 delegates in 1787 created and signed the U.S. Constitution. Jane is a presidential historian and author of “Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists and Women’s Right to Vote.” Her works can be found at Janecook.com. She is also the host of Red, White, Blue and You

Today is Constitution Day, commemorating when 55 delegates met in Philadelphia, in what is now called the Constitutional Convention, and – after months of deliberation – created and signed the U.S. Constitution on 17 September 1787. At the time, newspaper editors referred to the meeting as the Federal Convention, which met from May 24 to September 17.

GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives provide a window into the summer of 1787, revealing that some Americans were anxious. Many knew that their general government, which was formed under the Articles of Confederation during the American Revolution, was sweltering from the heat of a weak economy and a powerless federal government. The Federal Convention’s delegates needed to either amend the Articles of Confederation or adopt a new constitution.

Very little accurate hard news about the convention reached the public because the delegates were sworn to secrecy. They needed to debate freely without fear of their speeches appearing in the morning newspaper. However, some opinion writers voiced their opposition to the convention’s silence.

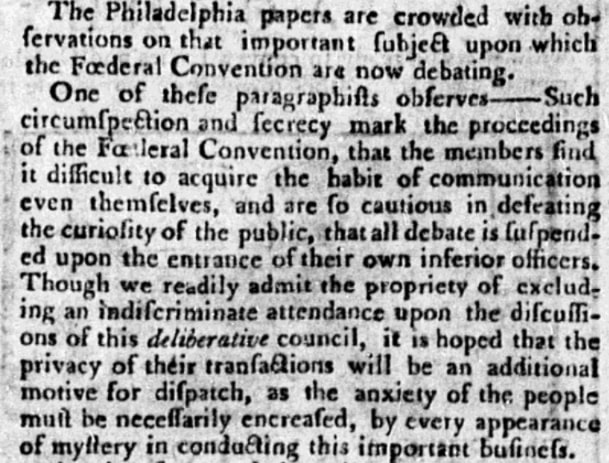

This article comments:

Such circumspection and secrecy mark the proceedings of the Federal Convention, that the members find it difficult to acquire the habit of communication even themselves, and are so cautious in defeating the curiosity of the public, that all debate is suspended upon the entrance of their own inferior officers. Though we readily admit the propriety of excluding an indiscriminate attendance upon the discussions of this deliberative council, it is hoped that the privacy of their transactions will be an additional motive for dispatch, as the anxiety of the people must be necessarily increased by every appearance of mystery in conducting this important business.

This vacuum of convention news troubled many, but this letter “from a gentleman in Baltimore” managed to express some cautious hope.

His letter says:

“How are the times with you? Here they are bad enough – no money in circulation, and consequently no trade. The expectation of the people seems to be fixed on the grand convention now in your metropolis [Philadelphia]; but nothing has transpired. It is said by some observers of nature, that it is often darkest before break of day. The political horizon of America is at present dark indeed; but I hope it will soon break forth into a glorious dawn of light and liberty; otherwise the friends of the Revolution will have labored and bled in vain!”

Others were more optimistic than cautious, declaring that unity guided the convention and suggesting that Philadelphia’s Federal Hall should be renamed to reflect it.

This article reports:

So great is the unanimity, we hear, that prevails in the convention, upon all great federal subjects, that it has been proposed to call the room in which they assemble Unanimity Hall.

Still others accurately observed that those who most opposed the Federal Convention – governors and state officials – had the most to lose under a new constitution.

This article reports:

It is agreed, says a correspondent, on all hands, that our convention [is] framing a wise and free government for us. This government will be opposed only by our civil officers, who are afraid of new arrangements taking place, which shall jostle them out of office. If these men are wise, they will be quiet, by which means they may succeed to their old offices – but if they are not, they may, probably, share the fate of the loyalists [to the Crown] in the beginning of the late war.

One writer accurately predicted that the convention’s outcome would be a peaceful and historic civil revolution.

This article comments:

Whatever measure may be recommended by the Federal Convention, whether an addition to the old constitution, or the adoption of a new one, it will in effect be a revolution in government, accomplished by reasoning and deliberation; an event that has never occurred since the formation of society, and which will be strongly characteristic of the philosophic and tolerant spirit of the age.

Finally, the convention’s secrecy ended on 17 September 1787, when the U.S. Constitution was signed by the delegates, the Pennsylvania Herald reported the next day.

This article reports:

The Speaker presented a letter to the House from their delegates in convention, of the following purport, viz. that they were happy in being able to inform the House, that the convention had agreed upon the constitution of a federal government for the United States, and that the delegates were ready to report to the Legislature, at any time that should be appointed.

Soon, newspapers around the nation published the U.S. Constitution in its entirety, leading with the now famous words:

“We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America.”

The delegates wrote a letter explaining the Constitution that many newspapers printed.

This letter says:

“We have now the honor to submit to the consideration of the United States in Congress assembled, that Constitution which has appeared to us the most advisable.

“The friends of our country have long seen and desired that the power of making war, peace and treaties, that of levying money and regulating commerce, and the correspondent executive and judicial authority should be fully and effectually vested in the general government of the Union.”

The letter explained that the convention’s delegates kept in mind “the greatest interest of every true American” and “the consolidation of our union.” They believed that the new Constitution would provide future “prosperity, felicity, safety, (and) perhaps our national existence.”

Although September 17 was the day that the convention adopted the U.S. Constitution, state conventions met throughout the nation to ratify the U.S. Constitution, which became the law of the land on 21 June 1788 when the ninth of 13 states ratified it.

Today, Constitution Day gives school children an opportunity to learn about their government and celebrate their freedom. Likewise, groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution celebrate Constitution Day by reciting the Constitution’s Preamble and hosting special events. Though not a national holiday, Constitution Day reminds Americans of the document that cemented the United States of America into a nation of the people, for the people and by the people.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: Independence Hall’s Assembly Room, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Credit: Antoine Taveneaux; Wikimedia Commons.