In a cage in the Cincinnati Zoo on 1 September 1914, Martha, a passenger pigeon, drew her last breath. With her passing something tragic happened: the passenger pigeon became extinct. Martha had been the last of her kind, the sole survivor of a species once so numerous only the buffalo and the locust could rival their staggering numbers.

They are largely forgotten now, but the huge flocks of passenger pigeons were once a dominant feature of the North American landscape. Journal entries from early explorers and settlers marvel at the huge numbers of birds they encountered. A later account from 1866 claimed a flock three hundred miles long passed overhead. Their great flights would darken the skies for hours.

The birds were intensely communal, thronging together in nesting sites that occupied thousands of acres, building hundreds of nests in each tree. The volume of their cooing was said to be so loud that it drowned out the sound of a gunshot, and when the flocks flew overhead people said they made the noise of a roaring river or a pounding waterfall.

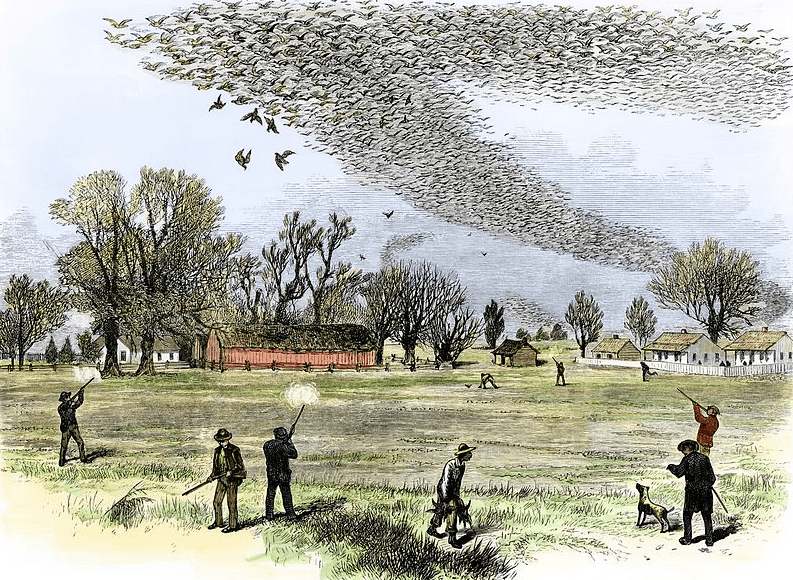

Human beings caused the extinction of the passenger pigeon. For one thing, the birds were slaughtered indiscriminately. People used to fire wildly at the flocks flying overhead for sport, seeing how many they could bring down with each shot.

Then someone realized money could be made off these birds, and the commercial meat industry sealed their doom. Hundreds of thousands were netted, shot and clubbed to death, then shipped in boxcars. They were used as a cheap source of meat for slaves, then after the Civil War as food for the poor.

The other factor in their demise was deforestation. The passenger pigeon required vast expanses of woodlands for nesting sites and for food (acorns were a favorite). The increasing loss of habitat, coupled with the wholesale slaughter of the flocks, sealed their doom.

The following four newspaper articles are about Martha’s death and the extinction of her kind. The first two articles report Martha’s death.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Sic Transit

A few days ago a distinguished individual died at Cincinnati. It was the last survivor of the once numerous race of the passenger pigeons. These birds had the habit in the days of their prosperity of flying southward in the Fall and returning to northern regions in the Spring. Persons now in middle life can well remember their migrations in the states of the Mississippi Valley. They began in the Fall with the first frosts and ended when the acorn crop was gone.

The flock of pigeons would become visible like a small cloud on the horizon. Gradually coming into full view, it expanded across the sky and sometimes clouded the entire segment from zenith to horizon with millions of invisible birds pressing upon those in the fore. Boys of that day watched the phenomenon with wonder. Where did all the pigeons come from? Where were they going? Their roosting places were in the hardwood forests which have vanished with the pigeons. Hundreds gathering on great oak limbs broke them from the trees. They swept the ground clear of acorns and other edible nuts and berries.

The birds were slaughtered with ruthless thoughtlessness. Young men caught them by the wagonload from their roosts by night. It was a favorite amusement to shoot into the dense flocks as they settled among the trees, killing hundreds “for fun.” Queer stories were told by the Winter firesides of the pioneers about wonderful pigeon hunts. One man had fired a bullet which split an oak limb where the birds were roosting. Their toes were pinched in the crack and thus he caught an even hundred alive with one shot. Every boy knew dozens of these tales and cherished the ambition to do something similar when he had a gun of his own.

In a few years the flocks of pigeons mysteriously diminished. When the boys who wondered at them in their teens had reached voting age they were seen no more. Today a passenger pigeon is a great rarity. Perhaps the one which died the other day in the Cincinnati zoological garden was the last of them. It is thus that we have dealt with all our natural resources.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Last Passenger Pigeon Dies

Death of the Bird in Cincinnati Zoo Makes Species Extinct

CINCINNATI, Sept. 2. – The passenger pigeon, the last of its species, died yesterday at the zoo. It is believed the bird died of an apoplectic stroke, as it had a similar stroke several years ago. It was found dead beside the low roost made for it when it became too infirm to fly to its accustomed roost.

The bird was a female and the Cincinnati Zoo had a standing offer out for several years of $1,000 for any person who would find a male so that the race might be preserved. The dead bird was 29 years old. The carcass will be shipped to the Smithsonian Institution at Washington.

The North American passenger, or wild pigeon, is especially interesting from the marvelous numbers composing its flocks before the settlement of the interior of the country caused its almost total disappearance.

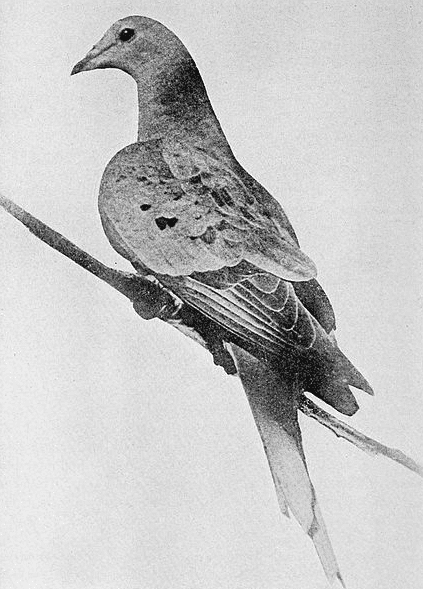

It is a large, slender bird, with a small head, notched beak, turned at the base, short, strong legs with naked feet; a long, acuminate tail and very long, pointed and powerful wings. It is a beautiful bird, with very graceful form and finely colored plumage, and formerly was found in almost all parts of North America.

The passenger pigeon is not, properly speaking, a bird of passage, as apparently its movements are consequent on the failure of a supply of food in one locality and the necessity of seeking it in another. Its power of flight is very great.

During the early part of the Nineteenth Century incredible numbers of pigeons were wont to roost at night and nestle in certain breeding places in the forests of the Mississippi Valley, where sometimes one hundred or more nests were seen in one tree. These thickly settled sections sometimes extended over tracts forty miles in length. Flocks of the pigeons were often seen flying in great, dense columns eight or ten miles long, at a height of several thousand feet. Some careful observers have declared that on some occasions the flocks were one hundred and fifty miles long.

The noise of wings and cooing of voices in their nesting places was so great as to drown the report of a gun. The multitudes which settled on trees broke down branches by their weight.

Note: Such wanton destruction as the extinction of an entire species troubled some thoughtful people in 1914. The following two newspaper editorials are good examples. The first takes solace in the hopeful thought that the example of the passenger pigeon’s extinction will teach humanity to better protect endangered populations of other animals. The second editorial is darker, pursuing the thoughts of Darwin and Nietzsche and wondering what sort of future humanity’s destructive impulses will create – and this just weeks after the cataclysm of World War I had begun.

Here is a transcription of this editorial:

Last Carrier Pigeon

In a cage in a public park at Cincinnati, the last survivor of a dying race is perishing, says The Indianapolis News. Its death, perhaps, is not a matter of great importance, nor is it, at the same time, without its significance. When the veteran passenger pigeon in the Cincinnati cage breathes its last the species dies with it. Fifty years have not passed since these birds were numbered by the millions. Their swift flights darkened the skies, and a day’s length, from dawn to dark, did not suffice at times to mark the passing of a single flock. Today only one remains. In less than half a century the race has become extinct.

The dying bird in Cincinnati is thirty years old. When it winged its first flight its fellows still were numerous. They flew in countless legions from the Gulf to the Lakes and vast flocks of them were to be seen in the fields and meadows of Indiana. Men now of middle age saw them, in their boyhood, in numbers still amazing. When this last survivor, however, was first made prisoner, the passenger pigeon was passing. In the brief lifetime of a single bird the race had been effaced. Ruthless slaughter had wrought its havoc and only a drooping captive survived.

Naturalists have sought in vain the country over for a pair from which the race might be revived. The offer of generous reward failed even to discover a mate for the lonely prisoner. And now, even for her, the end has come. But the fate that has befallen this race has not been without some compensation. It drew attention, at least, to the necessity for protecting our native birds from indiscriminate slaughter. And from laws resulting, projected merely as means of protection, we have gone still another step until, today, we do whatever we can, not alone to protect the birds, but to increase their numbers.

We have learned a good lesson and, though we gained our knowledge at the expense of the extinction of the passenger pigeon, the passing of the species has not been in vain. It is safe to say that if human means can prevent, this tragedy of the bird kingdom will not be repeated.

Here is a transcription of this editorial:

The Conquered

The interminable struggle for existence is nowhere more starkly defined in words, as scientifically relentless as the fact itself, than in the writings of Darwin. Led on by the irresistible force of logic he depicted the ceaseless battle, out of which he was led to believe issued the promise of better things in the so-called survival of the fittest. Where nature pursues her inexorable course, the conclusion may be accepted, although the process must call for such unsatisfying thoughts as those in which Darwin himself indulged, as he remarked the apparently useless waste that accompanied the evolution of a better species.

So far as can be seen, there is but one factor that has ever been introduced to thwart and mar the natural development. That factor is man. Whatever may have been the slow operations, occupying ages in some instances, to bring about the annihilation of a given form of life, it can safely be said that no species has ever destroyed itself. Cataclysmic occurrences doubtless operated at times, where the mutual warfare might otherwise have left the conflict of contending elements an uncertain issue. Thus perished certain of the forms of life whose remains are found in the fossil formations buried beneath the advancing cold of the great ice age. Again, the struggle of one kind of animal life with another brought triumph over immense areas in favor of the stronger, while lands cut off from the conflict continued to perpetuate the weaker. Australia is an instance, with its living specimens of animals long since extinct in every other part of the world.

But man is the great exterminator. Within a generation he reduced the countless herds of buffalo that once roamed the Western prairies to a few hundreds, now preserved in the national parks. And at the present moment the last passenger pigeon in the world is said to be dying in the Cincinnati zoo. This bird, in the days of Audubon, and later, was so plentiful as to blot out the sun for hours in its annual migration and to break the limbs of the forests at night where it found its roosting places. One lone bird in the Cincinnati zoo, in [her] thirtieth year, is the sole living representative of those myriads.

The buffalo, the passenger pigeon, all of the conquered, fell before powerful destroyers. Not one, however, brought about its own extinction. Man alone fights himself. That this strange habit will ever bring about self-annihilation is not to be expected. Nevertheless, the change may be wrought in spirit, if not in form. Then will come the triumph of the superman, that Nietzschian creature which apotheosizes war, and finds the consummation of its highest morality in the destruction of the weak and helpless.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Have you found any references to the great flocks of passenger pigeons in the letters or journals of your ancestors? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.