Excitement raced through the streets of Boston on 1 June 1813 as word spread that the British frigate Shannon had appeared offshore, displaying her colors in a defiant challenge to the Americans. The U.S. frigate Chesapeake, under the command of Captain James Lawrence, sailed out in response.

The War of 1812 was nearing the end of its first year, and the Boston public was hungry to witness a victory for their young nation. Crowds swarmed atop every vantage point of high ground and climbed steeples and rooftops, while others put to sea in small boats, everyone eager for the battle ahead.

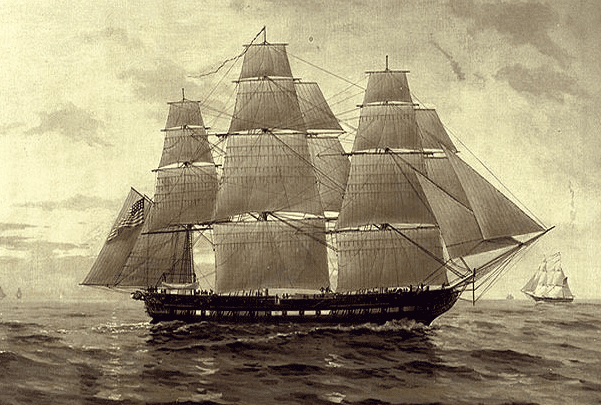

The waiting enemy was powerful, and ready. The 38-gun Shannon had been under the command of Captain Philip Broke for six years, and his crew was experienced and well-trained. By contrast, Lawrence had taken over the 36-gun Chesapeake just 11 days before the battle, and his crew was inexperienced and not fully trained. Nonetheless, Lawrence – who had already achieved significant victories in the war commanding the Hornet – was not one to back down from a challenge.

To the disappointment of the eager Boston crowd, the ships sailed too far east for the action to be observable from the shore. As it turned out, they were spared the pain of watching an American defeat. In a battle that lasted about 15 minutes and caused more than 250 casualties, the ships poured hundreds of cannon balls into each other before Broke led a British boarding party onto the Chesapeake, right after an explosion had dazed the American crew and set the ship on fire.

It was around this time that Captain Lawrence was mortally hit by rifle fire. Though in great pain, he declared to his men the enduring words: “Don’t give up the ship!” But bravery and courage were not enough on this day, and soon the British flag was flying atop the Chesapeake’s mast.

The British sailed the Chesapeake to Halifax, Nova Scotia. During the journey, on June 4, Lawrence succumbed to his severe wounds and died. He was 31 years old. The British repaired the ship, rechristened it HMS Chesapeake, and used it for another year before sailing it back to England in October 1814 for more repairs.

Lawrence lost his ship and his final battle, but his stirring words became a rallying cry for the U.S. Navy. During the important American naval victory over the British at the Battle of Lake Erie on 10 September 1813, Lawrence’s good friend Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry named his flagship Lawrence and flew a flag that boldly declared: “Don’t give up the ship” in big white letters on a blue background.

These newspaper articles show how the news of the Chesapeake’s capture was reported to the American public, as well as reports of Captain Lawrence’s stirring plea to his crew.

This first article shows how excited the Boston crowd was right before the battle, hopeful that it was about to witness a major American victory.

Here is a transcript of this article:

BOSTON, June 2.

EXPECTED BATTLE

Yesterday the Shannon, one of the largest and best appointed frigates in the British Navy, appeared in sight of this town. On perceiving this, the U.S. frigate Chesapeake, commanded by the gallant Capt. Lawrence, lying in President Roads, weighed anchor, and went down under a press of sail to give battle. The tops of houses, towers and steeples, were covered, vast numbers of our citizens went down to Nahant Cape-Ann, &c. and our harbor was crowded with small craft filled with people, to witness the engagement.

About dark, the town began to be filled with vague and contradictory reports, but nothing on which any reliance could be placed. This novel occurrence of two brave and well appointed ships of war, going out deliberately to fight a National Duel, made a serious impression upon the minds of all classes of our citizens, and a party spirit was entirely absorbed, and American sentiments again prevailed in Boston. By the morning or before, we expect to hear the bloody deeds of American and British valor.

Here is a transcript of this article:

Capture of the Chesapeake

On Tuesday forenoon the British frigate Shannon, Capt. Broke, appeared off our harbor, and displayed her colors.

The U.S. frigate Chesapeake, Capt. Lawrence, was then at anchor, just below Fort Independence. As soon as the enemy was seen, she fired a gun, and hoisted her colors. Preparations were immediately made for sailing, and when the Officers had assembled on board, and the tide served, she got underway. The Shannon proceeded down the Bay, and the Chesapeake followed under a press of sail.

Spectators were collected on every place in Boston which commanded a view of the sea, but the frigates proceeded to the eastward till lost sight of from the town, and our citizens on shore were thereby spared the distress of witnessing the result, a pain which those had to encounter who were spectators of the conflict in boats and vessels; and from whom the particulars of the battle, as far as present known here, are obtained.

The Chesapeake had a color at each mast head. That on the fore royal mast was white, and appeared to have some inscription on it. She was put under her topsails on approaching the enemy, fired a gun, and 10 or 12 minutes before six the cannonade became general and severe, and the Shannon experienced some injury in her spars and rigging, while the Chesapeake suffered no visible damage, and appeared to have the advantage of her antagonist. About 6, the Chesapeake, which was to windward, ran on board the enemy, and the contest continued yardarm to yardarm. In about 5 minutes there was a great explosion on board the Chesapeake, but whether caused by accident, or any new combustible used by the enemy is uncertain. Soon after the smoke thus caused had disbursed, the ships separated, and the English color (a blue flag) was seen over the American ensign inverted; and both vessels then stood to the eastward, undoubtedly for Halifax. From the manner in which the action was fought, neither of the frigates were essentially injured in their masts or rigging. Some fishermen who passed near the Chesapeake after her being taken, say she appeared considerably damaged in her stern.

We know not that any written challenge was received by Capt. Lawrence, but one intended for him reached Salem just after he sailed from Boston. If one was delivered on board the Chesapeake, duplicates were written.

Capt. Lawrence took the command of the Chesapeake a few days since. Some changes had also occurred in the other officers, and the First Lieutenant was sick on shore. For the same officers to be long associated we should conceive an advantage. Many of the sailors were fresh recruits, and little or no opportunity had been afforded to discipline them, as the business of equipping the vessel for sea was not completed. The enemy, on the contrary, there is reason to believe was specially prepared for a rencontre with the frigate President. All her officers and men had been for several months in the same relative situations – the complement in each respect was full – and the seamen had had every chance of being thoroughly exercised. From these circumstances Capt. Lawrence might, without impropriety, have delayed the interview, but he yielded to the impulse of his intrepid spirit as soon as he saw the foe, and whatever speculations there may be as to what would have been the mode of battle deserving preference (speaking after the event), no one doubts the bravery of the commander, officers and crew, and that he did what he considered best. Personal accidents early in the engagement may have contributed with the effects of the explosion to have produced the lamented result.

The officers and crews of both vessels must have suffered severely in the close and desperate contest, and fears are excited of a farther loss on board the Chesapeake by the explosion; and to the effects and confusion of this occurrence the unfortunate termination of the battle is generally ascribed.

The Chesapeake was rated 36 guns, but we understand mounted 49; the Shannon was rated 38, but, it is said, mounted 52 – and was superior in weight of metal. The number of men probably about equal. The Chesapeake had been refitted for a cruise and was nearly ready for sea.

Among the officers of the Chesapeake were many young gentlemen of this town – and till the particulars of the battle are known great anxiety will prevail.

All the accounts we yet have of the capture of the Chesapeake lead to a belief that the Americans did not strike their own colors.

Here is a transcript of this article:

“Don’t give up the ship!”

Said the gallant Lawrence, even in the moments of delirium. Such an exclamation was the offspring of true valor, the noblest trait of a noble soul. Perhaps a stronger and more honorable instance of the prevalence of the “ruling passion,” to the last, is not to be found. It exemplifies, what the English poet prophecied of his patriotic countryman:

“And you, brave Cobham, in your latest breath,

Shall feel the ruling passion strong in death;

Such in that moment, as in all the past,

‘O, save my country, Heaven,’ shall be your last.”

Here is a transcript of this article:

“DON’T GIVE UP THE SHIP!”

This is said to have been the dying exclamation of the gallant Lawrence. May it sink deep into every mind; and not only lead our brave tars to victory and glory, but animate the Crew of our National Ship to stand by it to the last, and never to strike their flag to any power under heaven. We are contending, as Com. Porter concisely expressed it in the motto at his mast-head, for “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights!” and should any dastardly wretch advocate a Peace before these important objects are secured, let the dying injunction of Lawrence be thundered in his ears – “Don’t give up the Ship!”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the War of 1812? Please share your stories with us in the comments.

Related War of 1812 Articles: