Introduction: Gena Philibert-Ortega is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.” In this blog article, Gena shows how DNA testing has been used recently to prove that the old rumor about President Warren G. Harding’s “love child” was true.

DNA testing is growing in popularity, with more and more genealogists using it to break through brick walls in their family history research. Historians, too, are using DNA testing to unlock mysteries from the past – most recently, to prove that the old rumor about President Warren G. Harding’s “love child” was true.

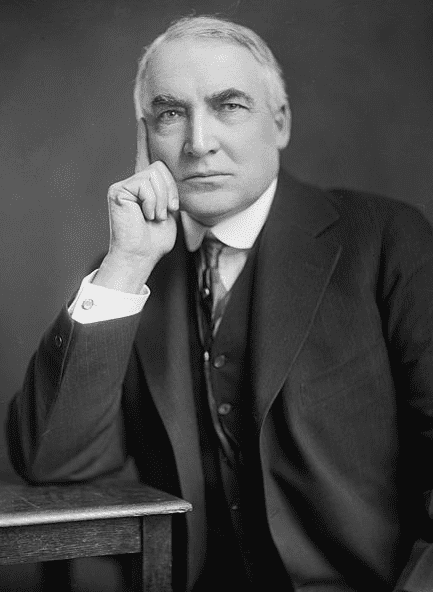

Long before Monica Lewinsky, Mimi Alford and rumors of other adulterous affairs carried on at the White House by Presidents Bill Clinton and John F. Kennedy, President Warren Harding was embroiled in multiple controversies – some of which came to light after his death. Government bribery via the Teapot Dome Scandal, an affair with Carrie Fulton Phillips (Mrs. James Phillips, a woman who successfully blackmailed him), and the later-discredited whispers that Mrs. Harding may have had a part in her husband’s mysterious death, all continue to blacken Harding’s legacy. And then there was the case of Nan Britton, who claimed to have had a nearly seven-year affair with Harding while he was married – and that he fathered her daughter Elizabeth.

DNA Testing Reveals Secrets from the Past

In an age before mobile devices that record and track your every move, lying about where you were, what you were doing, and who you were with was much easier. Without any way to “prove” a claim of an affair or resulting paternity, it was a matter of “he said” v. “she said.” Today, DNA testing is the ultimate game-changer. As far as familial relationships are concerned, DNA keeps no secrets.

In today’s world, it comes as no surprise to most of us to hear that a president had an affair (or multiple affairs) but in an earlier era, the truth was often easily covered up.

In the early 1910s, Nan Britton, a Marion, Ohio, teenager, was infatuated with local newspaper owner – and later U.S. senator – Warren G. Harding, who also happened to be her father’s friend. Harding, 31 years Britton’s senior, was carrying on an affair with local woman Carrie Fulton Phillips when the teenaged Britton began her obsession. When she was 20, Harding began his affair with Britton, which led to the birth of their daughter Elizabeth in 1919 – shortly before Harding was elected president. Britton would later claim that Harding provided financial support for their child but failed to mention her in his will, leaving Britton fighting unsuccessfully for her daughter’s inheritance when President Harding died suddenly during a trip to California in 1923.

Nan Britton’s Infamous Book

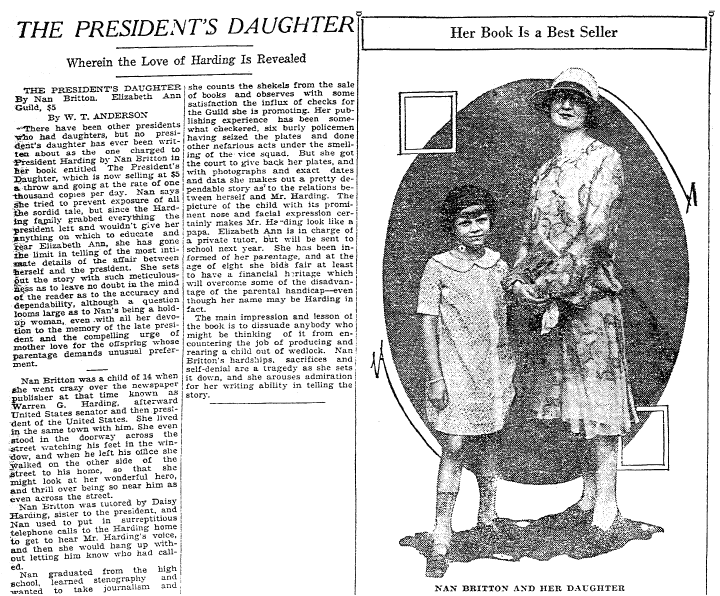

After Harding’s death stopped his financial support, Britton tried unsuccessfully to get Harding family members to provide ongoing compensation for his child. Britton then chose a route that modern-day readers are well-acquainted with: writing a tell-all book. The President’s Daughter (1927) told the story of her affair with Harding and their child. While Britton may have believed she was doing the right thing by her child, she probably didn’t anticipate the fallout she would experience from this decision to write a book about the affair.

Britton’s book met with controversy prior to its publication, including the printing plates being seized and attempts to block its release. In response, she started her own organization, The Elizabeth Ann Guild, which published her book. The Elizabeth Ann Guild’s purpose was to spotlight an important issue: the plight of “illegitimate” children.

Embroiled in Lawsuits

Those who write tell-all books often suffer the side effects of revealing very personal details. Imagine the Roaring ’20s and a woman, a self-proclaimed mistress at that, writing a book about “lurid” details that seek to tarnish the reputation of a U.S. president. Aside from being ridiculed for her paternity claims, Britton was involved in subsequent lawsuits having to do with her best-selling book.

[search_box]

One such suit involved her mentor (and what some believe to be the primary author of her book), Richard Wightman. In the following 1928 newspaper article, Patricia Wightman claimed her husband Richard – not Britton – wrote The President’s Daughter, which led to the demise of their marriage. Mrs. Wightman claimed:

…that her husband took Miss Britton into their home at Saybrook while he wrote the book from information supplied by Miss Britton, who acted as typist and secretary for him.

The book, and her husband’s involvement with Miss Britton, caused Patricia to leave and “live in a shack” before moving on to live in an exclusive hotel. She proclaimed that she:

…asked my husband not to have anything to do with the book…because it was scandalous and was an attack on the memory of a dead President.

According to a news report a few weeks later, Britton was named as a co-respondent in the Wightman divorce.

That was not the only lawsuit Britton was a party to. A book that claimed her allegations of an affair with Harding were false was published. Titled The Answer to the President’s Daughter, this work led to a lawsuit brought by Britton for libel. Another book that also aimed to discredit Britton was written by Harding’s campaign manager and attorney general, Harry M. Daugherty. Titled The Inside Story of the Harding Tragedy, it claimed to “refute Nan Britton’s claim that President Harding was the father of her daughter” as well as exonerate Mrs. Harding against claims that she murdered her husband.

Later Years

In the 1960s, the discovery of love letters from Harding’s affair with Carrie Fulton Phillips led to renewed interest in Britton’s story, resulting in follow-up newspaper articles. Britton knew the Phillips family and had gone to school with their daughter.

In this old news article, Britton lays out her life in the years after the president’s death that included living under assumed names and working hard to support her daughter. She also revisits her relationship with Harding and the subsequent financial need to write a tell-all book after his death:

…her motive for publishing the story of her love-life with Harding was grounded on the need for legal and social recognition and protection of all children born out of wedlock. She stated that in her opinion “there should be no so called ‘illegitimates’ in this country.”

While love letters from President Harding to Britton do not survive, those he wrote to Phillips do and have recently been released to the public, digitized and available on the Library of Congress website.

Nan Britton spent her life standing by her presidential love story and faced much ridicule for it. In this case the final “proof” endures in the genetic genealogy of a family. Britton died in 1991 in Oregon, still viewed with contempt by some who believed she told lies that tarnished Harding’s reputation. Her daughter Elizabeth died in 2005, ten years before the 2015 DNA test that proved the story that her mother consistently told all those years was the truth.

Related DNA Articles:

- DNA Needed to Solve One of the Oldest Missing Persons Cases

- DNA Shows That Jews Came from the Middle East

- Obama & Romney Are Related! Genealogy Infographic

[bottom_post_ad]