19th Century newspapers and handwritten records (such as the census) can be hard to read.

If you are having difficulty deciphering the handwriting or type, read through the issue of a newspaper or page in the census to see if other words on the page can give you clues to the editor’s or census taker’s writing style.

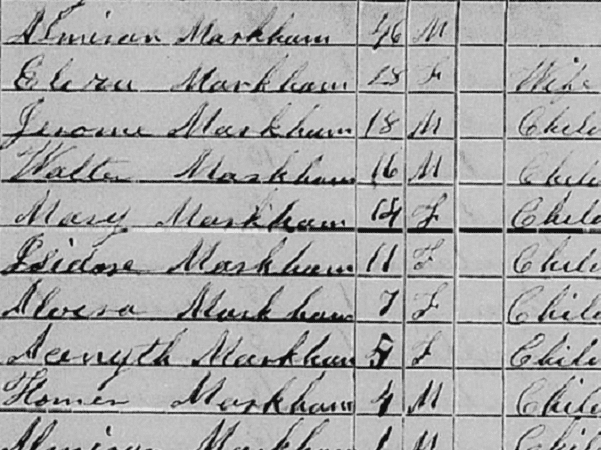

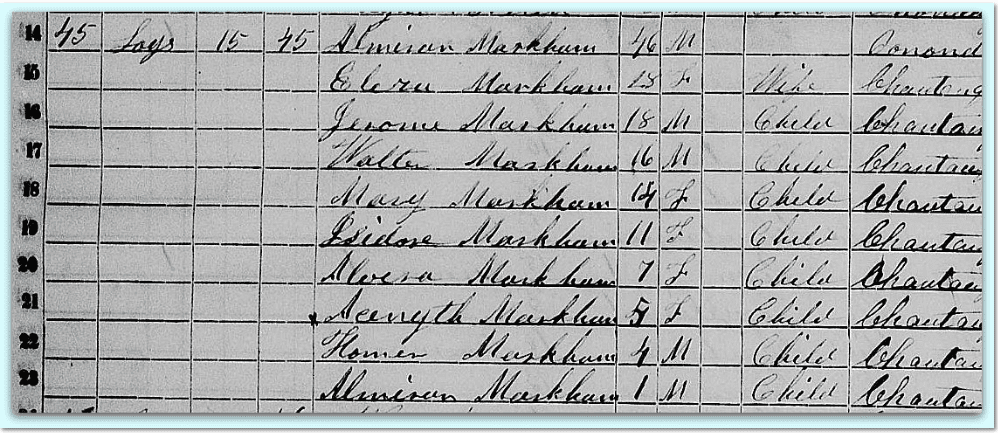

For example: here we have Eliza Markham living with her husband and family in Gerry, Chautauqua County, New York, as recorded in the 1855 New York State Census.

1855 New York State Census

https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/K6SG-7SG

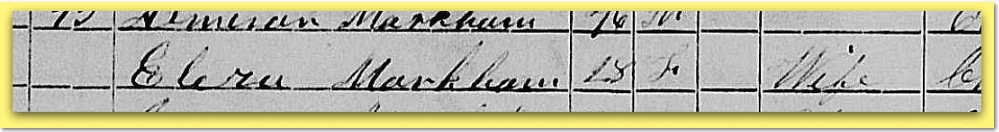

Look carefully at the handwritten entry for Eliza Markham.

1855 New York State Census

https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/K6SG-7SG

Is her name “Eliza” or “Eleru”?

Is this a 19th Century name you’re not familiar with—or is it simply a handwriting style you don’t recognize?

Not so simple is it?

As you look at each handwritten letter in her name, you have to think through the options. Some letters are easier to read then others.

What you want to do is to carefully review the other words on the page to become more familiar with the census taker’s handwriting.

Let’s examine each letter in this name:

- “E” – the initial letter has flourishes that make you wonder, but it is probably an “E”

“l” – yes, the second letter is clearly a lower-case “l” - “i” – the “i” can be a little tricky—I don’t see a dot over the “i”…is this an “e” instead?

- “z” – is that fourth letter an “r”? Would that fit? Looking at it again, it is probably the letter “z” written in the printed style instead of the cursive style

- “a” – what about this open-topped final letter—is it the letter “u” or an “a”?

In trying to determine if that final letter is a “u” or an “a,” look at other examples on that same page:

- Repeatedly the final “a” in Markham is written with an open top, much like a “u”

- The daughter’s name “Alvira” on the seventh line is written with an open-topped final “a”

- The family’s one-year-old son—and the father—also have a final open-topped “a” in their name

So, we can conclude from this handwriting pattern that her name was “Eliza.”

You will want to verify this by comparing the name to other genealogy records created in her lifetime.

Newspaper editors set and reset the pieces of type needed for each day’s newspaper. Broken type, ink spots, and gremlins of all sizes made their way into print and became a permanent part of the surviving newspapers—just like the imperfections in the handwritten records made by thousands of census takers a century ago.

FamilySearch Wiki has a handy multi-page chart of common spelling and transcription errors that were common in 19th Century printed newspapers and in handwritten documents like the census.

The “Intended” column shows what the letter was supposed to be, while the “Common Mistakes” column shows how the letter may appear.

See the FamilySearch common letter mistakes charts here: https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Spelling_Substitution_Tables_for_the_United_States_and_Canada

With these handy charts—and the patience to examine other examples on the page you’re viewing—you’ll find it gets easier deciphering difficult-to-read 19th Century newspapers and handwritten records.