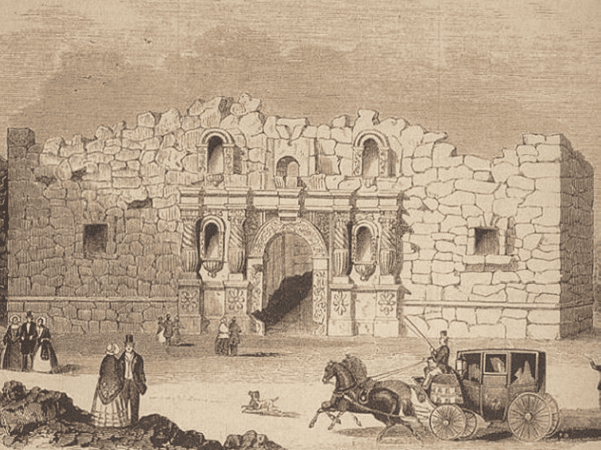

On the afternoon of 23 February 1836, 1,500 troops led by Mexico’s president General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna occupied the town of San Antonio de Bexar (modern-day San Antonio, Texas). Thus began the first day of the 13-day Battle of the Alamo, a legendary encounter in which all but two of the Alamo’s defenders were killed, including such famous figures as James Bowie, Davy Crockett and William B. Travis.

Their martyrdom inspired the fledgling Republic of Texas to “Remember the Alamo!” and defeat Santa Anna’s army the next month, securing its independence.

With reinforcements, Santa Anna’s force in Bexar swelled to 2,400 troops. Opposing him behind the walls of the crumbling adobe mission were approximately 200 staunch defenders willing to give their lives for the cause of freedom and Texas independence. (Varying accounts place the number of defenders anywhere from 182 to 260). Unlike Santa Anna, the men inside the Alamo received very few reinforcements, though as they grimly held on they kept expecting more of their fellow Texians (American settlers in Texas) to come to their aid.

The Battle of the Alamo was a significant turning point in the Texas Revolution that had begun 2 October 1835. While the Alamo was under siege, delegates at the Convention of 1836 declared independence and formed the Republic of Texas on 2 March 1836. After the Alamo garrison was wiped out March 6, more and more Texians and adventurers from the United States rallied to the cause of Texas independence.

In a surprise attack on April 21 that lasted only 18 minutes, the ragtag Texan army defeated the Mexican troops and captured Santa Anna, victoriously ending the Texas Revolution.

The Alamo martyrs had not given their lives in vain. Their example inspired their countrymen, as hoped for in a letter Travis had sneaked out of the Alamo to urgently plead for reinforcements.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The following is the official account of the engagement which took place in the town of Bejar [i.e., Bexar]; a short account of which we published a few days since.

Fort of the Alamo, Bejar, Texas, Feb. 25.

To Major General Samuel Houston,

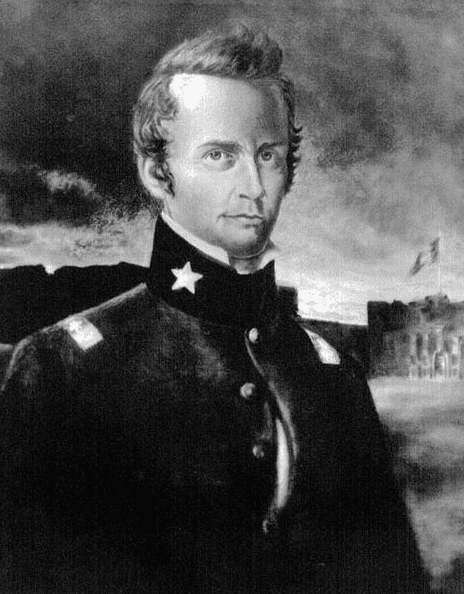

Commander in Chief of the Army of Texas,

Sir – On the 23d February the enemy in large force entered the city of Bejar, which could not be prevented, as I had not sufficient force to occupy both positions. Col. Batres, the Adjutant Major of President General Santa Anna, demanded a surrender at discretion, calling us foreign rebels. I answered them with a cannon shot: upon which the enemy commenced a bombardment with a five-inch howitzer, which, together with a heavy cannonade, has been kept up incessantly ever since. I instantly sent expresses to Col. Fanning, at Goliad, and to the people of Gonzales and San Felipe. Today at 10 o’clock a.m. some two or three hundred crossed the river below, and came up under cover of the houses, until they arrived within point blank shot, when we opened a heavy discharge of grape and canister on them, together with a well directed fire from small arms, which forced them to halt and take shelter in the houses about 80 or 100 yards from our batteries. The action continued to rage for about two hours, when the enemy retreated in confusion, dragging off some of their dead or wounded. During the action the enemy kept up a constant bombardment and discharge of balls, grape and canister. We know, from actual observation, that many of the enemy were killed and wounded – while we, on our part, have not lost a man. Two or three of our men have been slightly scratched by pieces of rock, but not disabled. I take great pleasure in stating, that both officers and men conducted themselves with firmness and bravery. Lieut. Simmons of cavalry acting as infantry, and Capts. Carey, Dickenson and Blair of the artillery, rendered essential services, and Charles Despallier and Robert Brown gallantly sallied out and set fire to the houses which afforded the enemy shelter, in the face of the enemy’s fire. Indeed the whole of the men, who were brought into action, conducted themselves with such undaunted heroism, that it would be injustice to discriminate. The Hon. David Crockett was seen at all points, animating the men to do their duty. Our numbers are few and the enemy still continues to approximate his works to ours. I have every reason to apprehend an attack from his whole force very soon; but I shall hold out to the last extremity, hoping to receive reinforcements in a day or two. Do hasten on aid to me as rapidly as possible; as from the superior numbers of the enemy, it will be impossible for us to keep them out much longer. If they overpower us, we fall a sacrifice at the shrine of our country, and we hope posterity and our country will do our memory justice. Give me help, oh my country! Victory or death!

— W. Barnet Travis, Lt. Col. Com.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors fight in the Texas Revolution? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.