It is sometimes said that the publication of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol in Prose; Being a Ghost Story of Christmas on 19 December 1843 invented our modern celebration of Christmas. This is an exaggeration, but there is no denying that Dickens’s enduring Christmas tale has had great influence on Christmas as we know it today. His story was an instant critical success in 1843 and has remained popular ever since, having never gone out of print.

By the year 1800 many of the early English Christmas traditions had been forgotten, replaced by a more somber religious observation of the birth of Christ. By the time A Christmas Carol was published, however, such modern celebrations as decorating a tree, sending cards, and singing carols had been established, and the season was once again becoming a time of merriment and festivity.

Dickens’s secular tale, with such memorable characters as Ebenezer Scrooge and Tiny Tim, and unforgettable expressions such as “Bah! Humbug!” enlivened the revival of Christmas as a time of joyous feasting and family gatherings. To this, Dickens added the memorable touch of his own genius: the cementing in the public’s mind of Christmas as a time of generosity and caring for those around us, especially the less-fortunate.

The following review of A Christmas Carol was first printed by the London Spectator, and shows that the book was immediately recognized as a classic. This review was reprinted by the Alexandria Gazette.

Here is a transcription of this article:

A Christmas Carol in Prose; Being a Ghost Story of Christmas

By Charles Dickens.

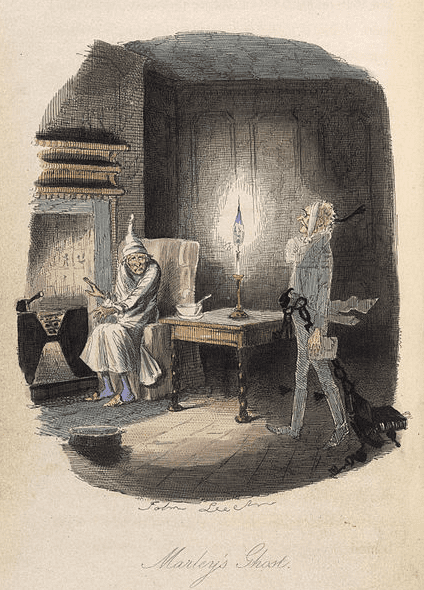

With illustrations by John Leach [sic].

Mr. Dickens has here produced a most appropriate Christmas offering, and one which if properly made use of, may yet, we hope, lead to some more valuable result to the approaching season of merry-making than mere amusement. It is impossible to read this little volume through, however hastily, without perceiving that its composition was prompted by a spirit of wide and wholesome philanthropy – a spirit to which selfishness in enjoyment is an inconceivable idea – a spirit that knows where happiness can exist, and ought to exist, and will not be happy itself till it has done something towards promoting its growth there. If such spirits could be multiplied, as the copies of this little book we doubt not will be – if no man would think the happiness of his own festive board complete unless, as he looked round on the merry faces which encircled it, he could curry his sympathies to some other as affectionate, though more humble circle, which he had made happy with some of the good gifts of Heaven – what a happy Christmas indeed should we yet have this 1843!

Mr. Dickens’s “Carol” is divided into five chapters, or “staves.” The first stave introduces us to a hard-handed, greedy old miser, Scrooge, who has no sympathy for the sorrows of others, because he cannot even understand what happiness means, except it mean hoarding money bags. The time is Christmas eve; the scene old Scrooge’s office in a dark court. His nephew comes to give him “a merry Christmas,” and to invite him to dinner on the next day. The old miser, in wrath, calls “Christmas a humbug,” and refuses the invitation. It is not without some grumbling that the poor old clerk, Mr. Cratchit, who writes all day on a high stool, in a cold little box, or “tank,” for fifteen shillings a week, obtains leave to stop away from business on the morrow.

A neighbor who comes to ask Scrooge for his mite towards a subscription for the starving poor “at this festive season,” is sent away with a flea in his ear; and the miserable old man goes from his dark office to his dark, solitary home, very angry at everybody for trying to make themselves and one another happy, if for only one day in the year. Arrived at home, and preparing for bed – he is visited by the ghost of his former partner, Jacob Marley (who has left him all his property), who warns him of the evil of his ways, and of the heavy chain which he is forging for his restless spirit after death, by his unceasing pursuit of wealth during life. The ghost’s doctrine is as follows:

“It is required of every man that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellow men, and travel far and wide; and if that spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world – Oh, woe is me! – and witness what it cannot share, but might have shared on earth, and turned to happiness… I wear the chain I forged in life. I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will, I wore it. Is its pattern new to you?”

The ghost then conjures up the apparition of other misguided spirits, as miserable as himself:

“The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley’s ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a doorstep. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, of good, in human matters, and had lost the power forever.”

The ghost then promises to send three spirits to the miser, who perhaps may work his reformation whilst yet it is time.

…But we must hasten to a close, or we shall be quoting half the book. The last of the three spirits (stave four) points out to Scrooge, in appalling truthfulness, the horrors of an old age and deathbed, unassociated with a single object of affection, a single subject for pleasurable reflection. All this is given with Mr. Dickens’s peculiar vigour of detail and coloring; until, at last, the affrighted man, upon contemplating his own dark, solitary, unwept gravestone, starts in his sleep and awakes “a wiser and a better man.” The transition from stave first is perfectly charming. Scrooge jumps out of bed with alacrity – dresses quickly – sallies out smiling; interchanges “Merry Christmases” with many happy folk; gives a munificent subscription (to make up for past years’ neglect) for the poor, to the neighbor whom he had repulsed but the evening before; sends the largest turkey he can find at the poulterer’s to his clerk Cratchit; and astonishes his nephew and niece by dropping into dinner; and the next day goes to the little dark office a cheerful man, and begins business by raising Cratchit’s wages.