Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry digs into old newspapers and archival records to tell the Prohibition-era story of Salisbury Police Chief Harold Congdon and the illegal rum-running operation he ran. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Author’s Note: This article was inspired from my column published in the “Newburyport Daily News,” 26 November 2014.

There have been two periods in American history when the government tried to temper “spirits.” In 1648 the general court passed a law limiting the Wampanoag tribe’s access to alcohol. In 1920 the entire nation was banned from the sauce during Prohibition, known as the “Noble Experiment.”

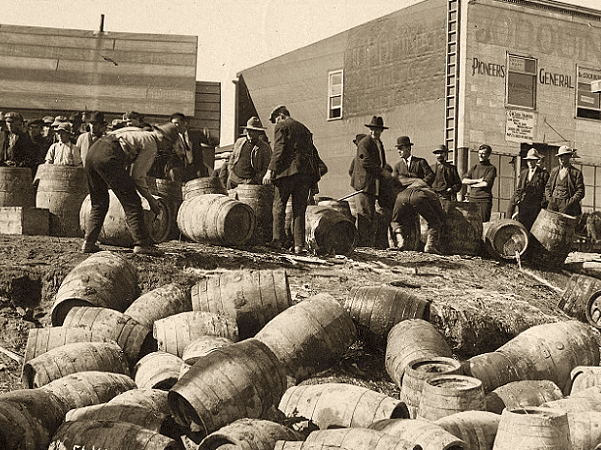

Efforts to restrain tipplers were unsuccessful and nothing could keep America dry. Folks wanted their wassail and few fell under the influence of the teetotaler reform. The number of liquor theft cases in the states was staggering, and federal courts were loaded with cases of illegal transport of liquor.

Salisbury, Massachusetts, was one hot den for a clandestine liquor enterprise that made a notorious buzz as the “most sensational liquor trial case in the history of federal courts.”

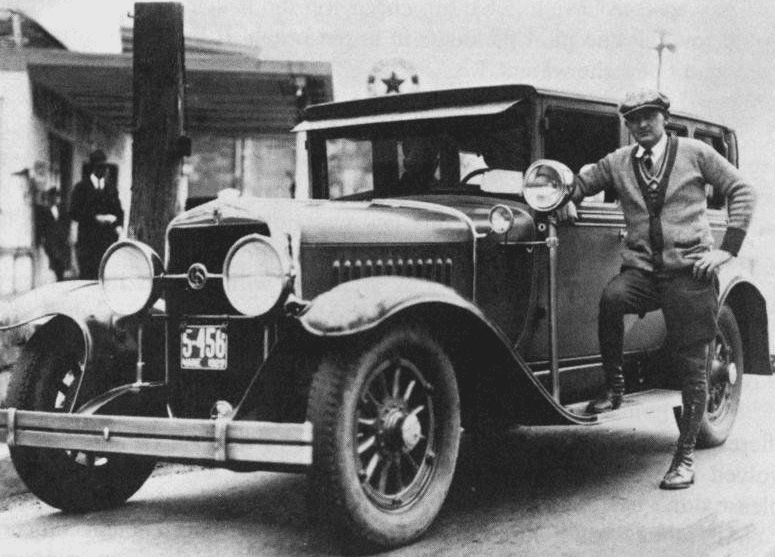

During Prohibition, smugglers transporting “white lightning” over land were known as “bootleggers” – and when over water they were called “rumrunners.” No matter how the hootch got in, there was much mazuma to be made.

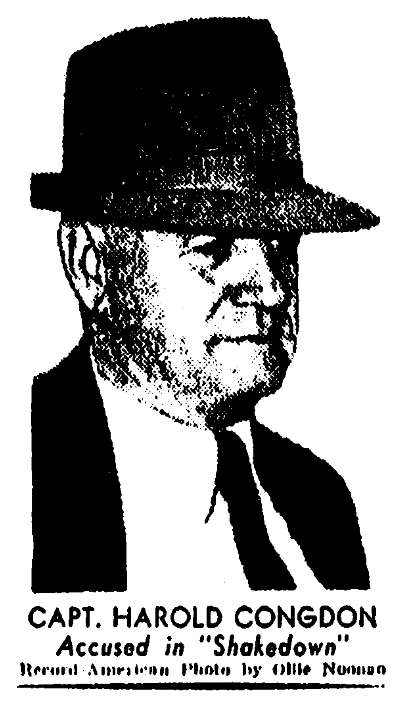

The Salisbury gang in 1923 had a most auspicious run. The leader, Police Chief Harold Congdon, aka “Captain Eddie,” was “juiced in” and his wife Sarah was his right-hand deputy. She mapped out the drops and scheduled the runs. The remote banks of the Merrimack River were an ideal area.

All was wine and roses as most of the police force, selectmen and Coast Guard were in on it. In fact, rumrunning became part of the community’s “official duties.”

However, human nature made a few greedy goers and the operation started to tank. Mrs. Congdon resented the fellows “drunk with power,” and the rumor was she had eyes for more than the chief.

Outsiders started to cut out the band even though they were using their turf to traffic. One of them was Anthony Caramango, aka “The Jap,” who flushed them out of a big score and the horns started to lock.

Mrs. Congdon, fed up, turned to the feds, but Captain Eddie’s $1,500 fund filtered in by officer Henry True bought him the stenographer’s court report. This seemed to “distill” the busy bodies for a brief time, but the feds were plotting a plan to teach these cowboys that a new sheriff was coming to town.

Henry Weaver, a federal agent, along with other officials out of Maine, busted the lot. Henry noted that “Salisbury was always a haven for bootleggers.” His boss ordered him to round up his best and make haste to Massachusetts to “catch a sheriff.”

The feds received tips and on 24 January 1924 they did the stakeout. Chief Congdon was there when the raid went down. He gave his crew the thumbs-up to start unloading and the agents jumped the fellows.

Over 30 indictments were brought down and there were two trials. The court was jammed with spectators for both. The Boston Herald covered the 2 July 1925 hearing and dished up the scandal.

Several witnesses told their stories and most went with the flow as loose lips were buttoned with a bottle from Captain Eddie. Another testified he saw “The Jap” sell a quart right at the police station in front of the chief.

Several reported piloting loads into town by orders of Congdon. Among them were Superintendent of Streets T. O. Corliss and Selectman Howard George, both paid $25 a night.

William Jackson, a teamster, was paid $30 for trucking the liquor but never associated with the “outlandish people.” Henry M. Fowler, Salisbury iceman, testified “The Jap” paid him $100 for four runs of liquor, from Black Rock Creek, that he carted to Pierce Cottage. William S. Eaton, a Salisbury farmer, caught wind of the ring while he was duck hunting at the “break of day” along Black River Creek. While Eaton was observing the obviously illegal activities, he was approached by officer True, who promised him a private stash which he could pick up “over at the Blaisdell home.”

Isaac Copeland of Salisbury gave testimony that he and his family experienced many sleepless nights due to the traffic from motor trucks carting the booze. He swore there were “32 on the eve of Thanksgiving.” When he complained, he was told “to mind his own business” and sent off with a quart.

The chief was put on the wrong side of the bars, but only for a short stint. Congdon served four months at Plymouth County Jail.

The chief and his wife Sarah ran against each other for town office in 1936, but he must have still carried a flame. Shortly after the election Congdon was charged with assault when he chased Sarah and her man friend off the road with his revolver. This time he had no problem telling the judge he was all liquored up!

According to an obit in a 1973 Amesbury newspaper, Captain Eddie ran an operation on Interstate 95 to extort speeders, which ultimately ended his reign and his pension.

It came to a screeching halt when he and his cohort Frederick W. Dow posed as state police officers and stopped Mrs. Doris L. Harkins and passenger J. Donald Barrios, both of Lewiston, Maine, at the Route 1 bypass near the John Greenleaf Whitter Bridge on the night of 13 May 1955.

Harkins testified in court on July 26 that Congdon and Dow “shook her down” for $15.

Harkins also stated Congdon gave her three choices: “(1) go to jail, (2) post bail and appear in court next morning, or (3) Give us $15 and a police officer will go to court, plead nolo for you and pay your fine.”

According to Ronald Guilmette, historian and retired Trooper, Massachusetts State Police, Congdon’s reign is a legend. Guilmette stated:

“The Congdon Toll Road is still talked about in police circles in Northern Essex County and the judge, Paul Kirk, former head of the State Police before being appointed on the bench, is often quoted, ‘The Congdon Toll Road is now closed.’”

Note: Just as an online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, told the stories of Harold Congdon, they can tell you stories about your ancestors that can’t be found anywhere else. Come look today and see what you can discover!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Thanks to Linda Dyndiuk, Head Librarian at Robbins Library, Arlington, Massachusetts, and Paul Colby Turner at Salisbury Historical Society.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Wood, Pam. “The Salt Book: Lobstering, Sea Moss Pudding, Stone Walls, Rum Running, Maple Syrup, Snowshoes, and Other Yankee Doings.” Garden City, New York: Anchor Press 1977.

- Berry, Melissa Davenport. Newburyport Daily News, “Captain Eddie and the Rum Runners,” 16 November 2014.