Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega writes about an important resource for African American history and genealogy: slave narratives recorded by the Federal Writers’ Project. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

Oral histories can be an important source for family historians. They provide context and information in a way that no other record can, especially for groups whose experience is not well-represented in the written record.

The WPA

The Works Progress Administration, later renamed the Works Projects Administration (WPA), was one of the programs that made up President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in 1933. The Works Progress Administration employed out-of-work Americans in various trades to do diverse work projects. Only in existence for eight years, the WPA employed approximately 8.5 million workers.

The WPA was responsible for a multitude of projects, including building roads, bridges, and other infrastructure. Humanities projects were also part of the WPA, hiring artists and writers. The Federal Writers’ Project was responsible for various publications that are now beneficial to family historians.

Federal Writers’ Project

As part of the WPA, in 1936 employees of the Federal Writers’ Project were sent to 17 states to write the life stories of ordinary people. Four of those states (Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia) documented the stories of African Americans who had previously been enslaved. In 1937 the projects in the other 13 states were instructed to also collect the stories of formerly enslaved men and women. This effort ended in 1939 when the Writer’s Project lost its funding. (1)

The end result of those interviews, Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, “contains more than 2,300 first-person accounts of slavery and 500 black-and-white photographs of former slaves” and is available online from the Library of Congress.

The digitized collection from the Library of Congress is organized by the state where the interview took place and the interviewee’s name. When searching the index, it’s important to remember that the person interviewed may have been enslaved in a different state than where they lived at the time of the interview.

WPA employees not only documented their interviews, but in some cases they took photos of the interviewee and their home (other images in this collection includes receipts and gravestones). Perusing the index will provide you not only the name of those interviewed, but the name of the interviewer and cities where interviews took place. States included are: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

Interview Examples

For family historians these interviews are important. They not only include biographical and genealogical details, but they include information about the area, the time period, and the community. While your family may not be represented in these interviews, the interviews still provide important information about experiences your ancestors shared.

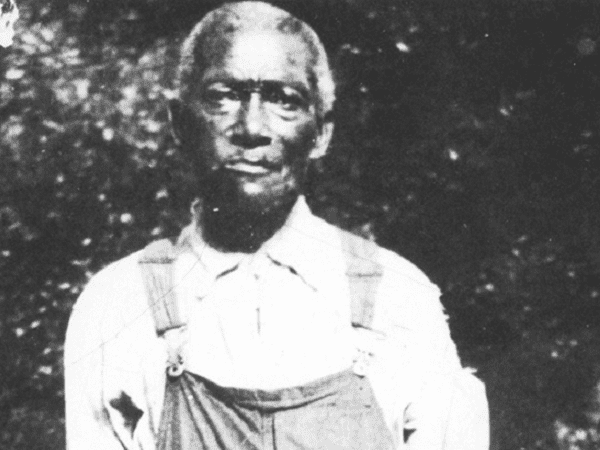

Steve Connally

Steve Connally was 90 years old and living in Texas when a WPA writer interviewed him.

He and his mother had been enslaved by Tom Connally, a member of the Georgia state legislature who was the grandfather of United States Senator Tom Connally (1877-1963). The family was originally from Georgia but moved to Texas after the American Civil War. Steve’s mother Mandy was the Connally’s cook, so some of his interview involves describing food – including how they kept butter, milk, and cream cold. Connally’s interview sparked a short newspaper article in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

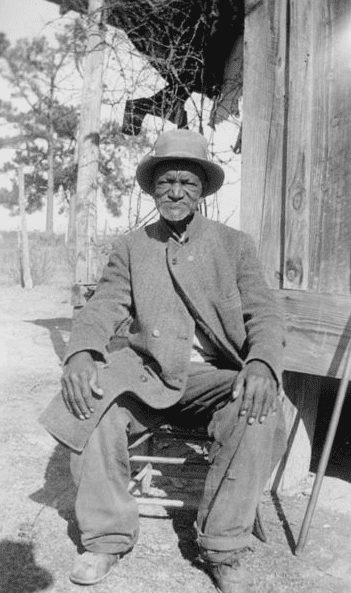

Henry Clay Moorman

As you search this collection of interviews it’s important to remember that although they are categorized by state and name, where the person lived at the time of the interview may be totally different from where they lived while enslaved. Such is the case of the Franklin, Indiana, interview with Henry Clay Moorman, who was enslaved as a child until the age of 12 in Kentucky on the James Moorman plantation.

Henry Moorman recalls his life on the plantation and gives insight into child rearing duties, stating that he and the slave owner’s child were the same age, and his mother and the other enslaved women acted as wet nurses. He also says that some of the white women acted as midwives for the enslaved women. Of interest to genealogists is his recollection of the cemeteries on the plantation, one for the family and the other for the slaves. He also provides information on slave weddings, including the fact that slaves often married partners from other plantations.

Mrs. M. S. Fayman

Mrs. Fayman’s story is different from many of the others in this collection. She explains that “I was born in St. Nazaire Parish in Louisiana, about 60 miles south of Baton Rouge, in 1850. My father and mother were Creoles, both of them were people of wealth and prestige in their day and considered influential.”

She goes on to explain she was attending a private school when she was kidnapped at about age 10 by a white man who transported her to Kentucky. She was taken to a slave trader’s home and because she spoke only French, she was made to tutor his children until she escaped in 1864. She provides details of her family tree including her parents’ names (Henri de Sales and Marguerite Sanchez de Haryne), and that her “grandmother was a Haitian Negress, grandfather a Frenchman. My father was Creole.” After she returned home in 1864, she completed high school, graduated from college, taught French and eventually marred a teacher.

Using the Collection

Some things to consider as you peruse this collection. Each interview is different – so the information and how it was documented varies throughout the collection. One criticism of the interviews is that, because the interviewers were white, the African Americans being interviewed modified their accounts. Some have argued that these interviews provide a “too positive view of slavery and plantation life. (2) Understandably, those interviewed were hesitant to tell their story to a white stranger. In fact, a few of the interviews I read remarked that the interviewee didn’t want to talk about anything unpleasant about slavery.

Keep in mind that these interviews reflect the time period. There are racist statements made by interviewers, and in some cases they attempted to document exaggerated and stereotypical speech patterns. These WPA workers were not experienced folklorists and these interviews reflect that.

One last point: historical newspapers also include stories of the formerly-enslaved. Newspapers tell the stories of some of those who were interviewed by the WPA, or who experienced a milestone – including living well into the 20th century.

The WPA interviews are available in various formats aside from the digitized copies on the Library of Congress website. For example, several books have been published that include these interviews, such as:

- How the Slaves Saw the Civil War: Recollections of the War through the WPA Slave Narratives by Dwight Eisnach and Herbert C. Covey

- What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods and Foodways from the Slave Narratives by Dwight Eisnach and Herbert C. Covey

- The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives by T. L. Baker and Julie P. Baker

- What the Slaves Believed: Recollections of Faith and Religion in WPA Slave Narratives by Tom Head

- Homeless, Friendless, and Penniless: The WPA Interviews with Former Slaves Living in Indiana by Ronald L. Baker

- Virginia Slave Births Index, 1853-1865 by Leslie A. Morales, Ada Valaitis, Jennifer Learned, and Beverly Pierce

To find these and other books using the WPA narratives, see WorldCat. The Wikipedia page Slave Narrative Collection includes links to the interviews and other works that were published using these interviews.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

__________________

(1) “About this Collection,” Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about-this-collection/ : accessed 6 February 2019).

(2) “Slave Narrative Collection, Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slave_Narrative_Collection : accessed 7 February 2019).

Related Articles: