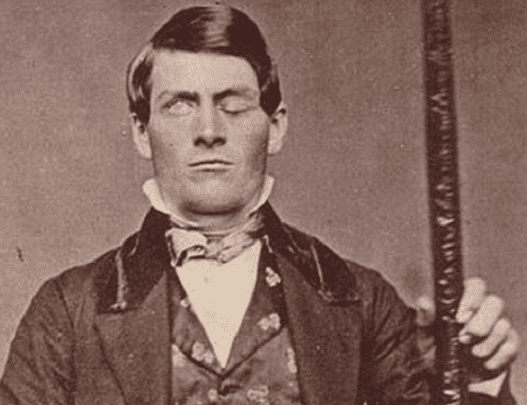

Phineas P. Gage, a 25-year-old foreman for the Rutland and Burlington Railroad in Vermont, was working with his crew blasting rock outside the town of Cavendish on 13 September 1848 when something astonishing and almost too incredible to believe occurred.

Gage was packing blasting powder into a hole with his iron tamping bar when a spark caused an explosion. With terrific force, the thick, heavy, 3½ -foot-long iron bar smashed into his left cheek and up through his brain, blasted out the top of his head, shot high in the air and landed about 80 feet away. Somehow, Gage not only survived this terrible accident – he never even lost consciousness!

Gage was knocked flat on his back by the accident. As his horrified men gathered around him, one retrieved the iron bar, covered in blood and bits of brain. Gage was conscious, and in a few minutes spoke to his men, got into an ox cart, and was driven ¾ of a mile to his lodgings.

Startled doctors dressed his wounds and everyone waited for Gage to die – which he did not do. In fact, in 56 days he seemed recovered, other than losing the sight in his left eye. He would go on to live another 12 years.

The left frontal lobe of his brain was almost completely destroyed, and in noting changes in his personality following the accident, doctors and scientists began to realize there is a relation between personality, behavior, and different parts of the brain. His story is an important case in the history of neurology, and his skull and iron bar are on display at Harvard University’s Warren Anatomical Museum, where they have been since 1868.

The local paper, the Ludlow Union, published an account of the accident the next day. That article was reprinted by the Nantucket Inquirer.

Here is a transcription of this article:

HORRIBLE ACCIDENT – As Phineas P. Gage, a foreman on the Railroad in Cavendish, was yesterday engaged in tamkin [i.e., tamping] for a blast, the powder exploded, carrying an iron instrument through his head, an inch and a fourth in circumference, and three feet and eight inches in length, which he was using at the time. The iron entered on the side of his face, shattering the upper jaw, and passing back of the left eye, and out at the top of his head.

The most singular circumstance connected with this melancholy affair is, that he was alive at two o’clock this afternoon, and in full possession of his reason, and free from pain. – Ludlow (Vt.) Union.

A month later Gage’s remarkable recovery was in the news, as well as an important clarification: the iron tamping bar was even thicker than had been originally reported, being 1.25 inches in diameter, not circumference. This 1848 newspaper article uses “wonderful” in the sense of “full of wonder.”

This article was published in Vermont by the Woodstock Mercury, and reprinted by the Alexandria Gazette – showing the far-ranging interest in the case.

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE “STRANGE CASE IN SURGERY.”

We gave some account, a few weeks ago, of the wonderful case of Mr. Gage, foreman on the railroad in Cavendish, who, in preparing a charge for blasting a rock, had an iron bar driven through his head, entering through his cheek, and passing out at the top of his head, with a force that carried the bar some rods, after performing its wonderful journey through skull and brains. The iron was in diameter an inch and a qua[r]ter, and in length three feet and seven inches; the upper end of the iron, however, tapering to the diameter of one-fourth of an inch. We repeat the dimensions of the rod, as we observe some of the papers that copied the article substituted the word circumference for diameter, thinking, perhaps, the story told in that way would be quite as large as could well be believed. But we refer to this wonderful case again to say that the patient not only survives, but is much improved: the wound in his head has healed, the scuttle in his roof is closing up, and he is likely to be out again, with no visible injury but the loss of an eye. – Woodstock (Vt.) Mercury.

Years after Gage’s death his family gave Dr. John Harlow, who treated Gage at the time of the accident, his skull and tamping bar for further study.

Here is a transcription of this article:

In 1848, Phineas Gage, of Cavendish, Vt., [had] a tamping iron three and one-half feet long, weighing thirteen pounds, blown by a quarry blast through the roof of his mouth and out at the top of his head, but got well in sixty days and lived thirteen [twelve] years, dying of disease in 1861 [1860]. Last week his skull was deposited in the museum of the Massachusetts Medical Society.

Twenty-five years later, a reporter examined the museum display of Gage’s skull and tamping iron and wrote this account for the Medical and Surgical Reporter. It was reprinted by the State.

Here is a transcription of this article:

A CROWBAR IN HIS SKULL.

The Most Extraordinary Case in the Annals of American Surgery

A correspondent of the Medical and Surgical Reporter writes: While in Boston recently I saw this skull and bar, and made the enclosed hasty sketch.

The story of this uncanny object is as follows:

Phineas Gage, aged twenty-five years, a native of Lebanon, N.H., was foreman of a gang of men who were employed in blasting rock at Cavendish, Vt. Gage had never had a day’s illness from childhood, and was, as far as could be determined, perfectly healthy.

At the time of the accident, on September 13, 1848, he was charging a drilling hole for blasting, and sat on a shelf of rock above, but a trifle to the right of the hole, as he faced it. The powder and fuse were in position, and he was in the act of tamping it in. He turned his head for an instant to look at his men at work behind him. His iron struck fire on the edge of the hole, an explosion followed, and the tamping bar, three feet seven inches long, one-fourth inch at the small end, about one and one-fourth inches at the large end, weighing about fourteen pounds, was projected upward obliquely in the line of its axis, passing completely through his head and high into the air, falling several rods behind him, and was afterward picked up by one of the men, covered with blood and particles of brain. The man was thrown upon his back by the force of the blow and his extremities moved convulsively a few times, but he spoke in a few minutes. His men carried him to the road a short distance away and he rode home in an ox cart sitting up by being supported. When he arrived at his destination he got out of the cart himself with a little assistance, and an hour afterward walked upstairs with a little aid and lay down upon the bed, where his wound was dressed. He was conscious, but very weak from loss of blood.

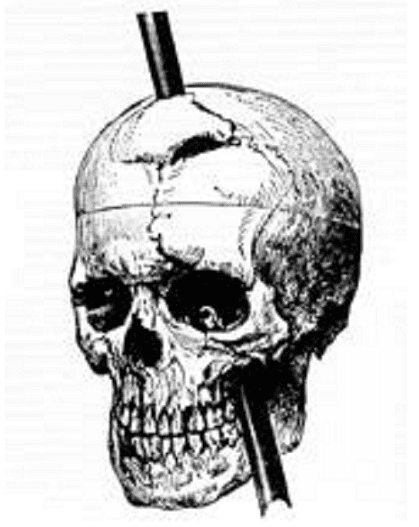

The examination of the wound showed that the iron entered the left side of the face by the pointed end, immediately anterior to the angle of the lower jaw, passed obliquely backward, emerging in the median line, back of the frontal bone, near the coronal suture. The bones were broken in small fragments and forced upward and outward. The hole had much the shape of an inverted funnel, the edges of the scalp everted and the frontal bone badly fractured, leaving an irregular oblong opening in the skull two inches one way and three and a half the other, through which the pulsations of the brain were distinctly seen and felt.

The wound was dressed and the man showed no apparent signs of serious injury excepting a curious agitation of the legs, which were alternately retracted and extended. Then began a battle, the natural consequences of such an accident against the strong constitution of a healthy man. No one thought it possible that he could recover, but after a few days he began to improve and the fifty-sixth day from the accident the patient was up and walking about the house and piazza. The sixty-fourth day he caught cold and serious consequences were, for a time, feared, but he recovered.

After that Gage was in good health and flesh, but in his mind was weak and childish, and the sight of the left eye was entirely lost. He visited South America, passed sometime in Valparaiso, then went to San Francisco, where his mother had moved. He died there of epilepsy, May 21, 1861 [1860], nearly thirteen [twelve] years after the accident. The skull and iron are now in the museum of the medical department of Harvard University.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Were any of your ancestors ever involved in a bizarre accident? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.