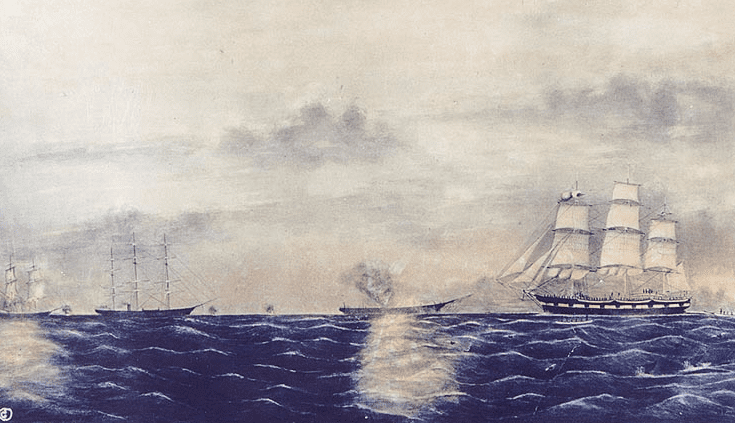

On 6 November 1865, one of the more remarkable sagas of the Civil War came to an end when the Confederate warship Shenandoah pulled into Liverpool, England, and Captain James Waddell surrendered the ship – seven months after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House had effectively ended the war!

During that time the Shenandoah had continued to attack Yankee whalers in the Pacific and Arctic Oceans, not realizing the war was over. In doing so, the Shenandoah fired the last shot of the Civil War.

During the year and 17 days that the Shenandoah was a commissioned warship it traveled 44,000 miles, carrying the Confederate flag around the globe, and sank or captured 38 ships – all merchant vessels. The Shenandoah never engaged a Union Navy vessel, and consequently its crew never suffered a war casualty.

Waddell’s surrender to British authorities raised two points of contention between the United States and Great Britain. For one, the Shenandoah had been built by the British and sold to the Confederate States of America for warfare against the United States, even though Great Britain had not officially recognized the legitimacy of the Confederacy. Voices were loud in the North that the British owed compensation for the losses inflicted on Yankee shipping by the Confederate raider.

The second point of contention was Waddell’s status. Would the British courts try Waddell as a pirate, since he was not obeying military orders from any legitimate government recognized by Great Britain? Complicating the situation further was Waddell’s contention that he was unaware of the war’s ending until 2 August 1865, when he met the British ship Barracouta – at which point, he claimed, he immediately sailed to England to surrender, fearing he might face piracy charges if he surrendered in a U.S. port. But what if he had actually found out sooner, and continued raiding for the sake of plunder?

The Albany Evening Journal (Albany, New York) carried the following two stories about the Confederate raider. The first, published on 20 November 1865, reported the Shenandoah’s surrender. The second article, published the next day, reprinted an editorial from the New York Times pointing the finger of responsibility directly at Great Britain.

Here is a transcription of this article:

FOREIGN NEWS.

End of the Shenandoah.

SHE GOES INTO A BRITISH PORT AND SURRENDERS.

PERPLEXING QUESTIONS AHEAD.

COMMENTS OF THE BRITISH PRESS.

New York, Nov. 20. – The pirate Shenandoah arrived in Mersey and surrendered to guard ship Donegal, and is now in the hands of the naval authorities. Capt. Waddell states that the first information he received of the close of the war was on the 30th [correction: 2nd] of August, from the British war vessel, Barracouta, and that he immediately consigned the guns to the hold and steered for Liverpool.

The Daily News says: “The Americans may be inclined to say it was only a fitting end that her end should be as British as her origin was;” but the Daily News cannot help asking “how the Shenandoah has been able to pursue her course without the least interruption of the American navy? Can it be possible that the expectation of recovering compensation for losses resulting from her depredations from the English Government made the Americans less eager for her capture? If the world should come to that conclusion, it would be one of the strongest practical arguments against the admission of such liabilities as Seward is now endeavoring to establish against England.” It is stated that Waddell sent a letter to Earl Russell [prime minister of Great Britain]; contents unknown. The captain and crew remained on the Shenandoah.

The Star says that the vessel will undoubtedly be claimed by America, and there is no reason for refusing the request.

The Times says that the question of personal liability and surrender after capture, will probably give rise to perplexing discussions; but that at whatever cost, strict justice will be done by the British tribunals to which it is submitted.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Pirate Shenandoah.

From the New York Times.

The Shenandoah, like a good many other Rebel curses, has gone “home to roost.” She turned up one fine morning in the port of Liverpool, carrying the Rebel flag, and was surrendered by her commander to an English man-of-war.

It will be seen by the extracts from English papers which we publish elsewhere, that her welcome is by no means cordial. It has ceased to be for English interests, and has therefore become immoral, to welcome the Rebel flag and fete the captains of Rebel privateers. The English, moreover, feel that the untimely arrival of the Shenandoah involves them in new and somewhat embarrassing responsibilities. It is susceptible of proof, we believe, that the Captain of this vessel, long after he had received authentic information of the termination of the war, pursued his career of plundering and burning peaceful and unarmed vessels, and that fifty or sixty whalers thus fell victims to his cowardly prowess in the Arctic seas. He claims to have received official intelligence of the close of the war only on the 30th [correction: 2nd] of August; but what particular form and style of information is requisite to check the black and bloody cruise of a privateer, it will now become the duty of English law courts to determine.

The responsibility of dealing with Waddell devolves wholly on the British Government. If he was in command of a privateer, duly exercising belligerent rights, England cannot surrender him, nor shall we ask her to do so. If, on the contrary, he pursued his career of devastation after those rights had ceased to protect him, he became simply a pirate, and violated the laws of Great Britain quite as truly as those of the United States. And it devolves upon the English authorities to hold him responsible. The fact that his depredations were continued to American vessels, and that British commerce suffered nothing at his hands, cannot, of course, alter the principles of justice and of law applicable to his case; though we should hesitate, in view of the recent events, to say that it will not alter the actual application of these principles by the British courts of law.

One thing, however, it may be well enough to bear in mind. The future application of whatever principles may now be laid down by English tribunals is of much more importance to England herself than is the fate of Waddell to anybody on the face of the earth. We wish the English neutrals joy of the return of their belligerent rover.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the Civil War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: