Introduction: In this article, Mary Harrell-Sesniak searches old newspapers to find memorable epitaphs from the 18th century. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

If you’ve followed the GenealogyBank blog, you’ve undoubtedly noticed the popularity of epitaphs. Applied to tombstones, epitaphs serve as simple reminders of what transpired in someone’s life.

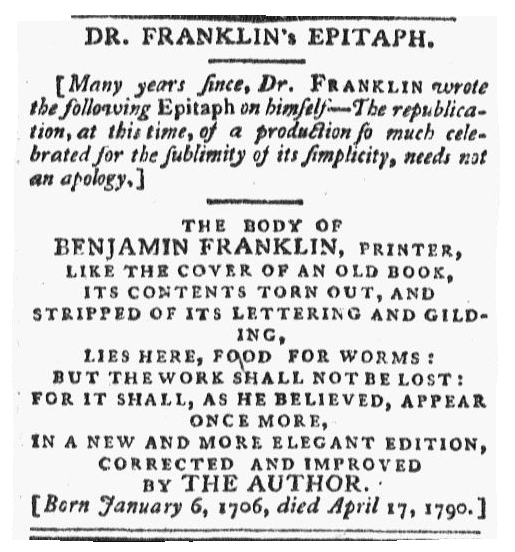

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

I’ve written before about Benjamin Franklin’s epitaph (see Curious & Funny Epitaphs of Famous People & the Not-So-Famous).

He took away from his survivors the daunting task of putting thought to pen by writing his own epitaph – when he was only 22 years old! Startling, but very memorable, Franklin described himself in his epitaph as food for worms.

The body of

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, printer,

Like the cover of an old book,

Its contents torn out, and

Stripped of its lettering and gilding,

Lies here, food for worms

Now that’s a memorable epitaph!

Interest in Epitaphs from before the 18th Century

Turns out interest in commemorative phrases is timeless. People of the past often put great thought, and sometimes tongue in cheek, into eternal remembrances. According to this reference from a 1736 newspaper article, a book on epitaphs was published more than a hundred years earlier, from which the editors selected an appropriate epitaph for a “Miser” who had died.

The editors certainly had no great love for this miser, as this epitaph’s two last lines make clear:

He liv’d a Hog, dy’d like a Dog,

And’s gone with many a Curse.

Westminster Abbey Epitaphs

Some of the most widely published epitaphs were used for burials in prestigious places, such as London’s Westminster Abbey. If you’re lucky enough to visit, try looking for these examples. The first one dates to 1721 and was written by the Duke of Buckingham “to be placed upon his Tomb in Westminster-Abbey.” According to WorldCat Identities, this was poet and politician John Sheffield (1647-1721).

His epitaph appeared in this 1721 newspaper article.

His epitaph speaks of his devotion to king, country and God:

I have Lived, often for my King, always for my Country,

Not without Danger, nor yet without Honour.

I Dye, uncertain of my Future State, but serene & undisturb’d.

I adore my Saviour Christ and acknowledge His Divinity.

I put my Trust in the Eternal and Omnipotent God alone.

Westminster Abbey is the final resting place of many other poets, such as Mathew Prior (1664-1721).

Prior left money for a monument to be erected in his memory at Westminster Abbey, along with some lines for his epitaph.

Here lies the Bones of Matthew Prior,

A Son of Adam and of Eve,

Let Bourbon or Nassau go higher.

After Prior’s epitaph was published, a newspaper reader decided to expand on the poet’s original lines.

Hold Mathew Prior, by your leave;

Your Epitaph is something odd,

Bourbon and You are Sons of Eve,

But Nassau is a Son of God.

Odd or Silly Epitaphs

Apparently epitaph writing was quite the art in the 18th century, and could be a form of humorous entertainment. Our ancestors often took pen in hand and coined silly epitaphs, such as this one for “Fanny” who had one brown garment, coarse and plain, and who was a virgin to her dying day.

Make sure you read this epitaph to the very end, so that you learn who Fanny was. Don’t you love the oddity and strangeness of this early humor?

Here is an odd epitaph with a taunt for the reader about getting rich.

Have you discovered any memorable epitaphs while doing your family history research? If so, please share with us in the comments section below.

Related Articles: