Introduction: Gena Philibert-Ortega is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.” In this blog article, Gena provides four tips, based on her own genealogy experience, to help you research your ancestors in historical newspapers – including a free Research Log template to help you organize and keep track of your searches.

Ok, so you have a weekend free. You decide to spend it on the hobby you love: family history research. You know you need to research in newspapers. But how do you start? Well before you sit down at the computer and start plugging in ancestor name after ancestor name, take a few minutes to plan out that research to make the most of the limited time you have. These four newspaper search tips will help you – and be sure to download the free Research Log template at the end of the article to help you with your genealogy research.

1) Whom to start with?

Sometimes just the hunt itself is the addicting part of genealogy research. Looking at old newspapers and reading old newspaper articles can quickly take up your available time. So before you get too engrossed in reading historical newspapers, focus your research and plan for each individual or family you’re interested in.

First, look at your pedigree chart and decide what your research question is. Do you want to find marriage notices for your most immediate family (parents and grandparents)? Do you want to learn more about that black sheep ancestor? Looking to follow your ancestor’s political career? Write down your research question before you start your research. It’s ok if that question changes as you find new information, but start with a specific question so that your research time has a focus.

2) Get the most out of your ancestor search.

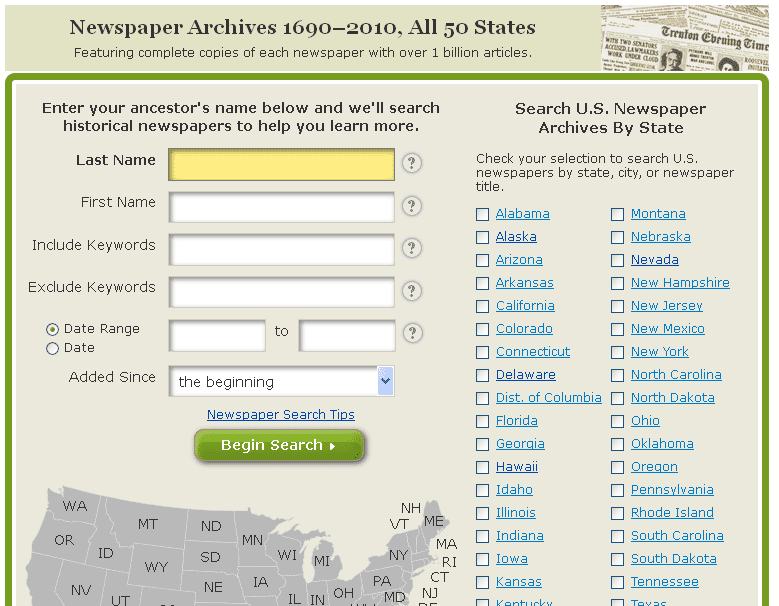

Not all genealogy search engines are equal. And to start searching without taking into consideration how that search engine works can result in a lot of frustration and fewer relevant results.

How is the GenealogyBank search engine different?

For one thing, the information it finds is via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and not by searching indexed or transcribed fields. (See the blog article Genealogy Search Engine Types & Tips: OCR vs. Indexed Databases.) Because the software does not recognize words but characters, keep in mind that difficulties can arise when the original newspapers are damaged, smudged, or have hard-to-read type.

Whenever you use a search engine, a good rule to remember is that the more information you add, the fewer results you will receive. In essence, as you fill the search engine with names, keywords, places and dates, you are asking for a very specific and narrow result. In some cases, this is important if you are looking for a specific event or place, or when you are researching a common name. But whenever your search results are few, always think about restructuring your search to make it broader. Try different variations of your search, such as using just a name and place, or simply a name and date.

One more tip for your search of GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives: don’t forget to utilize the menu choices located on the left hand side of your search results. These options provide you the choice to narrow your search result by the type of article. This is a wonderful tool to help you find what you need, especially useful when you know what kind of article you are looking for.

3) Get ready, set, search!

So now that you better understand how to search GenealogyBank it’s time to do the fun part: search! While you could just plug in ancestor names and download articles, consider what each historical newspaper article tells you and how you might change your search to accommodate new information you learned. Then consider follow-up searches on additional names, places or even a historical event so that you can place your ancestor in proper context.

As I research my ancestors, I often take some time to read the whole newspaper, reading every section, to get a sense for the community, what was going on, who was coming and going, etc. – you never know what part of the newspaper might hold information about your ancestral family. I even like to browse the classified advertisements to see how they are structured. For example, do funeral notices appear there? Do they have Help Wanted or Lost and Found ads that contain identifying information like addresses and names?

4) Document all your family findings.

Ok, so you found some great information about your family, now what? Don’t just save the articles on your computer to languish there until your next research session or – worse yet – to never be found again. Document your family history finds. Research Logs can help you do that by providing a place to insert what you found, note where you found it, and add any comments that you have for further research.

Free Research Log Template

Not sure what a Research Log is or how to start one? No problem; with this free download from GenealogyBank you’ll be tracking your research in no time.

Clicking on the link (or the graphic) will let you download the Research Log template as a full-size, working Excel spreadsheet that you can use to organize and track your genealogy research. This log is compliments of Duncan Kuehn, who provided the following instructions:

Crafting your research plan:

- Title: Give your document a title. This will likely be the name of the person or family line that you are working on.

- Objective: Craft a very specific objective. The more specific you can be the more effective your search will be. An example of a poorly crafted object would be: “Continue the Johnson line.” A better objective would be: “Find out when Jacob Johnson was born.” An even better objective would be: “Find out when Jacob Johnson (probable son of James Johnson and Sally Kunz) was born (likely 1882-1885 in Hardin County, Kentucky or Randolph County, South Carolina).” Having a clear objective keeps your search focused. Having more information helps you narrow your search and determine if you have found the right information.

- Date: Always enter a date for each entry. This will help you keep organized.

- Goal:Follow this basic outline for setting goals. Each goal or search should occupy its own row in the research plan.

- Confirm the known information.

- Identify which sources might contain more information. Prioritize these by likelihood to contain the information, reliability, ease of accessibility, quality, etc.

- Determine what possible documents might exist. For example, were birth certificates issued in the area at that time?

- Try to find the document.

- Check to see if any online resources have digitized the collection.

- If not, check to see if an online index exists.

- Check to see if any online resources have digitized the collection.

- Check to see if any near-to-you repositories have the collection.

- Check to see if any archives in the local jurisdiction have the collection.

- Obtain the document and analyze the information.

- Re-evaluate if the objective was met or not. If it was, then create a new research plan with a new objective. If not, determine what additional information is required and then identify which sources might contain that additional information.

- Source: Write down what source you are using to find the information. For example, when confirming the information where did you look? Was it on your family tree? Did you locate the birth certificate in your possession? Write down this source and include as much information as possible. Who authored it? What page in the book was it found on? What was the call number of the book? What was the URL of the online document?

- Repository: Write down where you found the source. Where was the document found? Was it in your possession? Did you locate it on FamilySearch? Was it in the local library? Write down as much information as you can here. If it is a place you intend to visit, be sure to include the address, phone number, website, etc.

- Result: Write down what you searched for and what you found. Be very, very specific. For example: “I searched for Jacob Aman’s (born 1901 in South Dakota) birth certificate on Ancestry, but nothing was found. I also used the spellings of Amman, Amann, Ammann, Anan, Amam, Amon, etc. I searched the time span of 1898-1903. I did not restrict it to a particular county.” That way when you think of or discover additional alternative spellings, such as Jakob or the initials J.B., you know to go back and try searching with the new information. When you do find information, record it here.

- #: Use this column to record the document number, include a link to the document that is stored on your computer, or list the document name as saved on your computer or in your paper files. You will want to access the document again. How will you find it? Enter that information in this column. Note: be sure to obtain a copy for yourself; don’t rely on finding the document again online, because URLs change, collections get culled and removed from websites, websites go defunct, etc.

Note: What is the difference between a research log and a research plan? A research plan includes the log, keeping all the information together. This prepares you for conducting the research: what documents exist, where can they be found? A research log would generally not include the goals of confirming the information, identifying the sources, locating where the source can be found, but instead would focus on the actual document search within a repository. This hybrid combines the best of both worlds to keep all the information in one place. I’ve called it a research plan because genealogists tend to focus on the document search when they need to focus on the preparatory work. The title is intended to remind them to slow down, focus their research, start at the beginning and work their way through. Once the document containing the information is found, the work is not done. Each fact needs to be confirmed by multiple sources. The evidence from each source needs to be properly evaluated. Finally, a written statement needs to be crafted to “prove” the answer, taking into account any evidence that contradicts the genealogist’s conclusion. Once this statement, paragraph, or report has been written, you are ready to move on – keeping in mind that new sources and evidence will be found and that might cause you to go back and revise your previous conclusions.

———————-

Spend some time this upcoming weekend researching your family in the newspapers. Nowhere else can you find such a rich variety of stories to help you better understand your ancestors’ lives and their world.

Related Newspaper Search Tips Articles: