The “Roaring ’20s” was a fast-paced, dizzying time of excitement and possibilities. Peace and prosperity had returned after the devastation of WWI, and new inventions and machinery were pushing frontiers and expanding former boundaries. A bold young pilot named Charles Lindbergh epitomized the spirit of the times, and he dazzled the world when he landed his plane in Paris after completing history’s first solo trans-Atlantic flight on 21 May 1927.

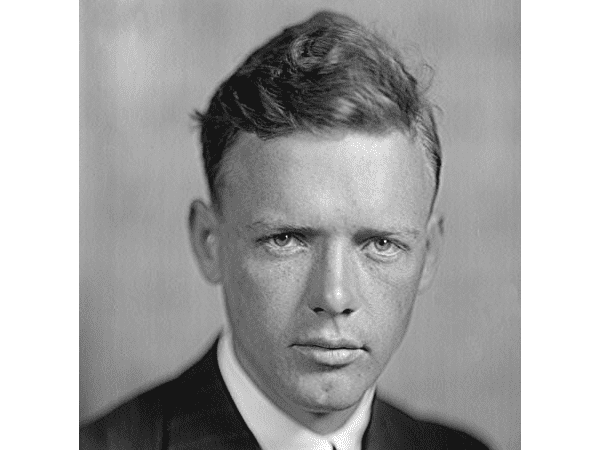

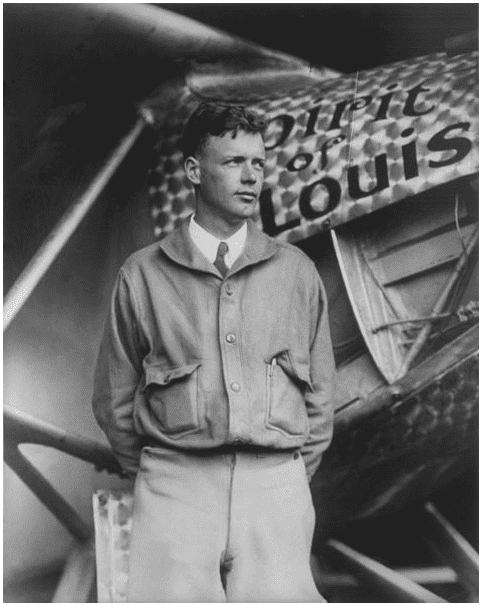

The 25-year-old airmail pilot was unknown when he flew his now-famous airplane Spirit of St. Louis from Roosevelt Field in Long Island, New York, to Le Bourget Field outside of Paris, France, in 33½ hours on 20-21 May 1927. He was after the Orteig Prize, a $25,000 reward that had been available since 1919 to the first pilot to fly nonstop between New York and Paris.

In the intervening years several attempts had been made, all unsuccessful, and six famous pilots had died. Just 12 days before Lindbergh took off on his successful flight, two French war heroes—pilot Charles Nungesser and navigator Francois Coli—departed Paris in pursuit of the Orteig Prize, but they and their plane disappeared forever after flying over the coast of Ireland.

The whole world seemed to embrace Lindbergh’s amazing aeronautical feat, and his daring and confidence were praised and rewarded. As a reserve Army officer he was awarded the Medal of Honor, and received the Distinguished Flying Cross from President Coolidge. He achieved wealth and lasting fame, and the unknown airmail pilot was obscure no longer.

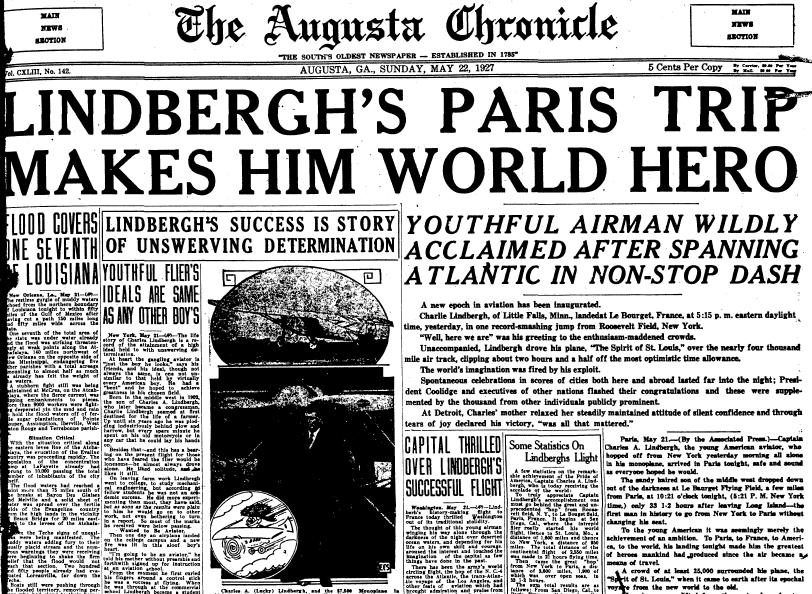

This historical newspaper reported:

A new epoch in aviation has been inaugurated.

Charlie Lindbergh, of Little Falls, Minn., landed at Le Bourget, France, at 5:15 p.m. eastern daylight time yesterday, in one record-smashing jump from Roosevelt Field, New York.

“Well, here we are” was his greeting to the enthusiasm-maddened crowd.

Unaccompanied, Lindbergh drove his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, over the nearly four thousand mile air track, clipping about two hours and a half off the most optimistic time allowance.

The world’s imagination was fired by his exploit.

Spontaneous celebrations in scores of cities both here and abroad lasted far into the night; President Coolidge and executives of other nations flashed their congratulations and these were supplemented by the thousands from other individuals publicly prominent.

At Detroit, Charles’ mother relaxed her steadily maintained attitude of silent confidence and through tears of joy declared his victory “was all that mattered.”

The old newspaper also reported Lindbergh’s reception when he landed in France:

To the young American it was seemingly merely the achievement of an ambition. To Paris, to France, to America, to the world, his landing tonight made him the greatest of heroes mankind had produced since the air became a means of travel.

A crowd of at least 25,000 surrounded his plane, the “Spirit of St. Louis,” when it came to earth after its epochal voyage from the new world to the old. The airman was lifted from the seat, where for two days and a night he sat fixed, guiding his plane over land and sea, and for 40 minutes he was hardly able to talk or do anything else, except let himself be carried along by a mass of men made delirious with joy at his achievement.

Never has an aviator of any nation, even king or ruler, had a greater or more spontaneous welcome from the hearts of the common people of France. The very recklessness of his endeavor, as it appeared, appealed to the quick emotional imagination of Frenchmen, and they were quick to respond with everything their own hearts could give.

All ties of nationalism were forgotten by the Le Bourget throng. They saw in Lindbergh only a man who had brilliantly gambled with death and won. There was regret, for Nungesser and Coli, and regret, too, that the daring Frenchmen had not been the first. But there was no bitterness in their greeting of the American winner.

GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives are a great way to discover the details of your ancestors’ lives—as well as learn about the times they lived in. Come search today and see what amazing feats your ancestors accomplished during their lifetimes!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial