Introduction: In this article, to celebrate February being Black History Month, Mary Harrell-Sesniak searches old newspapers to find information about 10 African Americans who achieved notable “firsts” in American history. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

So rich is the history of persons of color, that when GenealogyBank asked me to research historical African American accomplishments, it was difficult to narrow the choices.

As a result, this article focuses on just a few famous African American women and men of the 18th and 19th Centuries. This list includes transformational leaders, authors, inventors and the people behind many of the “firsts” in American history. At the conclusion of this article, follow the links to further broaden your knowledge of these famous African Americans, as well as other notable people who could not be featured in this short piece.

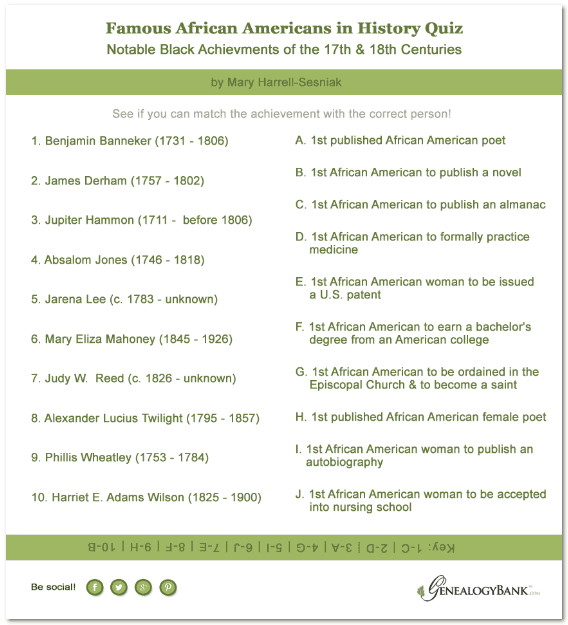

For researchers of Black history who know these earlier achievers as household names, take this handy quiz—which you are welcome to share with others.

For everyone else, read on to learn more about these individuals, with information gleaned from GenealogyBank’s online Historical Newspaper Archives.

1) Benjamin Banneker (9 Nov. 1731 Baltimore, MD – 9 Oct. 1806 Baltimore, MD)

Early newspapers described Banneker as “a noted Negro mathematician and astronomer”—but he was also a farmer, clock-maker and self-taught scientist. In addition, he was the first African American to author an almanac.

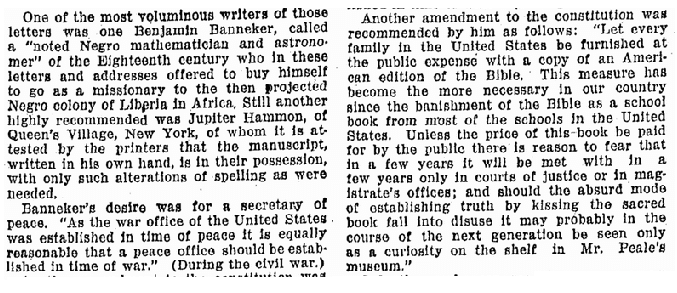

Banneker was chosen to assist Major Andrew Ellicott with his project to survey the borders of the District of Columbia. Known to be a voluminous writer of letters, Banneker became involved in the movement to establish the colony of Liberia in Africa. He was never enslaved, as his parents, Mary and Robert, were free.

(See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Banneker.)

2) James Derham (1757 Philadelphia, PA – 1802)

Although he did not hold a degree, James Derham became the first African American man to formally practice medicine, a skill he learned during the Revolutionary War while serving with the British under his master, Dr. George West. Derham was fluent in French, English and Spanish. As someone taught to compound medicines, he was an early pharmacist. His medical business in New Orleans, Louisiana, reportedly earned him $3,000 per year.

This 1789 newspaper article presented a biography of James Derham.

In this 1828 newspaper article, a local New Orleans doctor expressed his admiration for James Derham’s medical knowledge:

‘I conversed with him on medicine,’ says Dr. Rush, ‘and found him very learned. I thought I could give him information concerning the treatment of diseases, but I learned more from him than he could expect from me.’

3) Jupiter Hammon (17 Oct. 1711 Lloyd Harbor, NY – before 1806)

Hammon was an abolitionist, the first published African American poet, and is largely considered to be one of the founders of African American literature. Enslaved by the John Lloyd family and never emancipated, he was allowed to write and even served in the American Revolutionary War.

One of his poems, “An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries,” was published as a broadside (i.e., a paper printed on a single page).

(See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_Hammon.)

For more information about his life, see: Authentication of Poem Written by 18th Century Slave and Author, Jupiter Hammon (Cedrick May, University of Texas at Arlington).

4) Absalom Jones (1746 Delaware – 13 Feb. 1818 Philadelphia, PA)

Born into slavery, Absalom Jones was a noted abolitionist who became the first ordained African American priest of the Episcopal Church, in 1795. Early newspapers depict him as an articulate and educated man, who worked to establish a free colony of former slaves in Africa. In the Episcopal Calendar of Saints, 13 February is celebrated as “Absalom Jones, Priest 1818.”

(See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absalom_Jones.)

5) Jarena Lee (c. 1783 Cape May, NJ – unknown)

A noted Evangelist, Jarena Lee was the first African American woman to publish an autobiography.

The earliest mention of Jarena Lee in a newspaper was in 1840, when she was listed as a member of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society from Pennsylvania.

Another report from an 1853 newspaper mentions Lee involved in a discussion about the Colonization Society.

6) Mary Eliza Mahoney (16 Apr. 1845 Dorchester, MA – 4 Jan. 1926 Boston MA)

After working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, Mary Eliza Mahoney became the first African American woman to be accepted into nursing school, at the age of 33. It took 16 months, after which only 3 of the 40 applicants graduated. By 1908 she had co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) with Ada B. Thorns. She went on to be an active participant in other nursing organizations, along with holding titles as a director. When women gained their voting rights in 1920, Mahoney was the first woman in Boston to register to vote. Several prestigious nursing awards are given in her honor.

(See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Eliza_Mahoney.)

7) Judy W. Reed (c. 1826 – unknown)

Judy W. Reed is often hailed as the first African American woman to hold a patent, for her dough kneader.

http://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=00305474&homeurl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect1%3DPTO2%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%25252Fnetahtml%25252FPTO%25252Fsearch-bool.html%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526co1%3DAND%2526d%3DPALL%2526s1%3D0305474.PN.%2526OS%3DPN%2F0305474%2526RS%3DPN%2F0305474&PageNum=&Rtype=&SectionNum=&idkey=NONE&Input=View+first+page

Not much is known about her life, but this 1900 newspaper article reports that she and several other women received their patents in 1899.

(Note: Google patents reports that they were earlier. See: https://www.google.com/patents.)

8) Alexander Lucius Twilight (26 Sep. 1795 Corinth, VT – 19 June 1857 Brownington, VT)

Twilight was a licensed Congregational minister, a teacher and politician. In 1823 he became the first African American to earn a bachelor’s degree when he graduated from Middlebury College in Vermont. He also became the first state-elected official when he joined the Vermont General Assembly in 1836.

(See: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/twilight-alexander-1795-1857.)

9) Phillis Wheatley or Phillis Wheatley Peters (8 May 1753 Senegambia, Africa – 5 Dec. 1784 Boston, MA)

Hailed in this 1773 newspaper as “the ingenious Negro Poet,” Phillis Wheatley was the first African American female poet to be published.

Captured at the age of seven in the present-day regions of Gambia and Senegal, Africa, Phillis found herself enslaved by the John Wheatley family of Boston, who taught her to read and write. At the age of 20, this talented woman published Poems of Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, which was showcased in America and England. After the death of John Wheatley, she was emancipated and decided to marry John Peters. The family struggled financially, and after Peters was sent to prison for debts, Phillis became ill and died at the young age of 31.

(See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Wheatley.)

10) Harriet E. “Hattie” Adams Wilson (15 Mar. 1825 New Hampshire – 28 June 1900 Quincy, MA)

Born to an African American “hooper of barrels” and a washerwoman of Irish descent, Hattie was raised by her parents until her father died. As a young girl, she found herself abandoned and bound out as an indentured servant on the farm of Nehemiah Heyward, Jr. After completing her indenture, she worked as a seamstress and servant. Some of her other occupations were: clairvoyant physician, nurse and healer. In 1851 she married Thomas Wilson, an escaped slave and lecturer. He soon abandoned her, but later returned to rescue her and her son from a poor farm.

(See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harriet_E._Wilson.)

Harriet is credited with writing the first African American novel published in the U.S. Although copyrighted, “Our Nig: or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, was published anonymously in 1859 and rediscovered by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in 1982. Although a work of fiction, the book is thought to describe her life as an indentured servant. I couldn’t find any early newspaper articles to document her life or her novel, but I did find several recent articles discussing her work—including this one from 1982.

For more information, see: African American Registry.)

Additional African American Research Resources

For more complete biographies on these and other noteworthy African Americans, see: