By Vernon Case Gauntt

Editor’s Introduction: Earlier this year, we posted a fascinating three-part article written by Vernon Case Gauntt about the remarkable life of his third great aunt, Mary Sawyers Swan, whose life story reads like unbelievable fiction – except every word Vernon (he goes by Casey) wrote was true. (Casey is an accomplished writer. If you enjoy this story, check out his website: Write Me Something Beautiful.)

Now we post another incredible tale from Casey’s family tree, proving once again that truth is stranger than fiction – and that genealogy is endlessly fascinating. Today’s story involves a WWII disaster, when munitions exploded while being loaded on a pier in California on 17 July 1944, killing 320 and wounding another 390. Most of the victims were African American sailors.

Such an important and complicated event requires a bit of story-telling, and so we are presenting the tale of the Port Chicago Disaster in three parts over three days.

- Two days ago we posted the first part: Remembering Port Chicago, Part I

- Yesterday we posted the second part: Remembering Port Chicago, Part II

Casey’s Introduction: July 17 marks the 75th anniversary of the disaster at Port Chicago in the San Francisco Bay Area of California, when 320 men were killed loading munitions onto two ships bound for the South Pacific. Never heard of Port Chicago, California? Neither had I until this January when my uncle Stan Case, my wife, and I were on a road trip to Willits to meet with the folks who were of immense help to me with the Mary Sawyers story. As we drove over the back bay into San Francisco, my uncle reminisced:

“Back in the 1940s during WWII, my dad’s company, Case Construction, was building a pier in Port Chicago. There was a huge explosion at another pier close by, and a lot of men were killed including, I believe, some Case employees.”

My interest was piqued and I began to do some research. My GenealogyBank subscription came in handy as I found several newspaper articles about the explosion, the Case project, and the resulting fight led by Thurgood Marshall to end the Navy’s policy of strict segregation. Here is that story.

Marshall Continues the Fight for the Port Chicago 50 and an End to Segregation in the Military

This case was far from over. As he prepared an appeal on behalf of the men, Thurgood Marshall continued to press Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal to investigate the injustices at Port Chicago.

Although publicly brushing off Marshall’s demands, privately Forrestal expressed concern that the Navy’s strict segregation policy was actually hampering the war effort. A few experiments of assigning black sailors to work alongside whites on ships had gone well.

In early 1945, the Navy assigned more black sailors to integrated crews aboard ships, and the first black naval officers were assigned to ships at sea. More white sailors were moved into unpopular shore duty assignments, like ammunition loading. The change was gradual, but it was real change. [from Steve Sheinkin’s 2014 book “The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights”]

In May of 1945, Marshall’s appeal was rejected by the Navy who found:

“The trials were conducted fairly and impartially. Racial discrimination was guarded against.”

The legal process may have come to an end, but the trial in the court of public opinion had not.

In August of 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies and World War II came to end. Marshall, other members of the public, and some Congressmen continued to press Secretary Forrestal to reexamine the fate of the Port Chicago 50.

Even Eleanor Roosevelt, the widow of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, weighed in with a brief note to Forrestal:

“I hope in the case of these boys, special care will be taken.”

Secretary Forrestal made his decision with little fanfare and even less explanation. In January 1946, the Port Chicago 50 were released from prison and returned to active duty for service on ships at sea.

A month later, the Navy became the first branch of the military to officially eliminate all racial barriers with this historic order:

“Effective immediately all restrictions governing types of assignments for which Negro personnel are eligible are hereby lifted. Henceforth they shall be eligible for all types of assignments in all ratings in all activities and all ships of the naval service.”

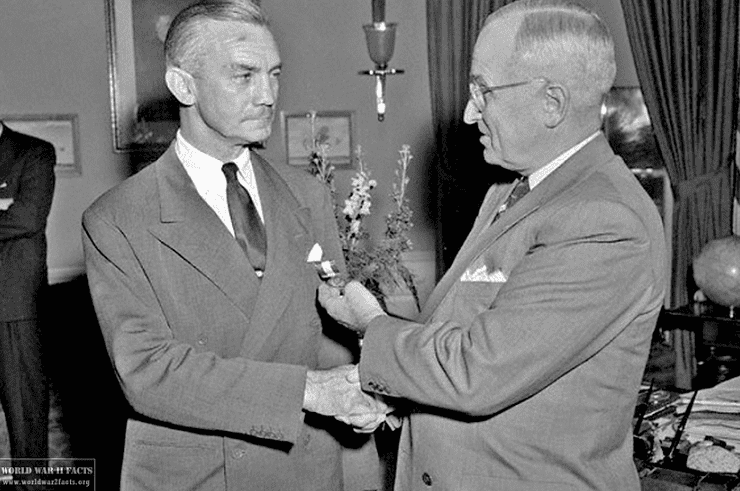

This was followed two years later by the Executive Order of President Harry Truman ending segregation in all branches of the military:

“It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.”

Thurgood Marshall cautioned:

“We have just begun to scratch the surface in the fight.”

But this was a major step forward in the battle for equality, desegregation and respect. And it began with the 202 African American sailors killed at Port Chicago at 10:18 P.M., Monday, 17 July 1944.

This story is dedicated in memory of and respect to those men and all 320 of the men who lost their lives at Port Chicago.

Postscript

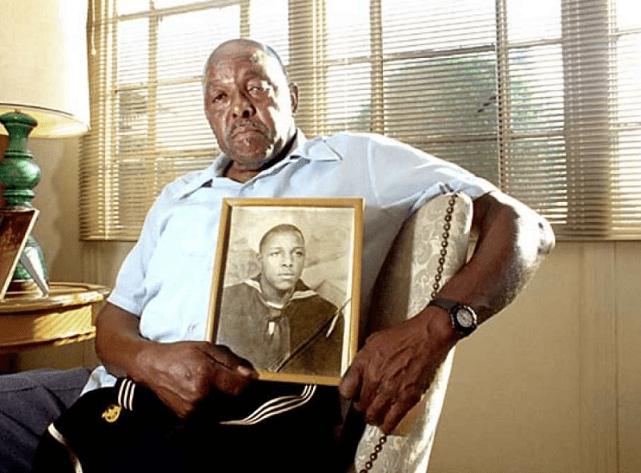

Upon completing active duty, the Port Chicago 50 were discharged “under honorable conditions.” This meant they performed their duties satisfactorily, but their records contained a disciplinary action. They were never exonerated from their mutiny convictions, although one sailor, Freddie Meeks, did receive a pardon from President Bill Clinton in 1999. They were entitled to veteran health care benefits, but could not participate in the GI Bill which provided free college education.

All of the Port Chicago 50 have passed on.

Macco-Case’s contract with the Department of the Navy provided for the lump sum payment in full only upon completion of the pier. Construction was about 95 percent complete when it was destroyed by the explosions at the other pier. Vern Case travelled to Washington, D.C., to plead their case to the Navy. The Navy didn’t budge: no completed pier, no payment.

Macco-Case had fronted a lot of money on the project and faced serious financial problems. Fortunately, they discovered they had insurance which covered their loss. The insurance company paid the claim and then went after the Navy for reimbursement. That dispute dragged on for another 20 years.

Vern Case admitted:

“I had no idea if our insurance policy covered us, but I’m sure glad it did!”

The piers were never rebuilt.

Acknowledgements

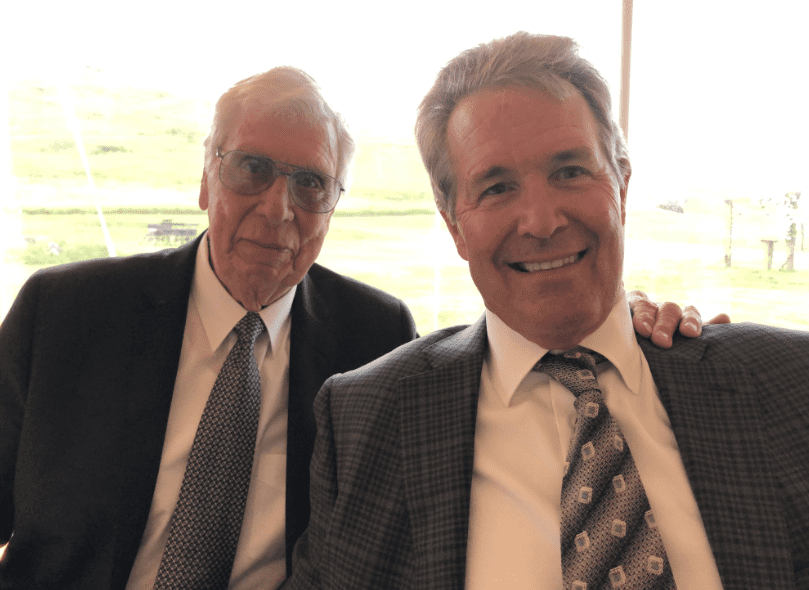

I want to thank my uncle, Stanford “Sandy” Case, for bringing the Port Chicago story to my attention. In January of 2019 we took a family research trip to Willits in Mendocino County where a lot of our ancestors were born and raised, including my grandfather (Stan’s father), Vern Case. I also traveled there to thank the folks at the Mendocino County Historical Society who helped me with the Mary Sawyers Swan Cook story. As we drove back over the Bay to San Francisco Stan reminisced about his dad’s company building a pier in Port Chicago.

Thanks to GenealogyBank and its extensive Historical Newspaper Archives, I quickly found the horrific details of the explosions, references to the Macco-Case joint venture, and the identities of the three employees who were killed. I also began to read about the Port Chicago 50 and the enormous injustices suffered by these men, the other survivors, and the 202 African American sailors who were killed.

This led me to Steve Sheinkin’s terrific book published in 2014, “The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights,”

Note: If you enjoyed this story and would like to read Casey’s first story posted earlier this year, here is that original introduction and links to the three-part article about his third great aunt, Mary Sawyers Swan.

Editor’s Introduction: Here is a story that will interest all kinds of readers. This is a tale brimming with drama, history, and incredible events. And for family historians, this narrative is a vivid reminder that our ancestors’ lives were filled with stories just waiting to be discovered – though perhaps not all as astonishing as this one.

The story of this story began back on 12 September 2017, when we published this article on the GenealogyBank blog: A Fortune Lost at Sea: Ship Sinks with CA Gold Rush Treasure. More than a year later, Vernon (he goes by Casey) Gauntt posted this comment: “My third great aunt, Mary Sawyers Swan, was on that fateful voyage of the SS Central America with her husband, Samuel P. Swan, and their 21-month-old daughter, Martha ‘Lizzie.’”

In a follow-up correspondence, Casey said his aunt had a remarkable life: “This woman finds herself in the middle of some of the greatest events in this country’s history: early pioneer, wagon trains, Indian attacks, Gold Rush, one of the most disastrous ship wrecks of all time, Civil War, fires, San Francisco earthquake, and brushing shoulders with a U.S. President.”

Intrigued, we invited Casey to tell our readers his aunt’s story, which you are about to read. (Casey is an accomplished writer. If you enjoy this story, check out his website: Write Me Something Beautiful.) Such a long and eventful life as Mary’s requires a bit of story-telling, and so we are presenting the tale of Mary Sawyers Swan Cook in three parts over the next three days. Enjoy!

- The True Story of Mary Cook, Part I: Wagon Trains, Gold Rushes, Shipwrecks, Wars, Fires, Earthquakes, Love & More!

- The True Story of Mary Cook, Part II: Wagon Trains, Gold Rushes, Shipwrecks, Wars, Fires, Earthquakes, Love & More!

- The True Story of Mary Cook, Part III: Wagon Trains, Gold Rushes, Shipwrecks, Wars, Fires, Earthquakes, Love & More!

Here is a comment from my good friend, John Morehouse, from New York

I enjoyed your story very much. I recall my grandfather who owned a commercial printing business in Oakland and lived in San Francisco telling me about the incident at Port Chicago. He was working in his plant the evening of the explosion and heard it and ran outside because he thought his building might collapse. My father enlisted in the Navy after graduating from Cal in 1942 and was an officer on the USS Pomfret, a submarine, stationed in the Japanese Islands at the time of the explosion.

Your story about the Port Chicago incident reminded me of a book I read recently. The Great Halifax Explosion, by John Bacon, recounted the story of the great Halifax, Nova Scotia explosion on Dec. 6, 1917. The French freighter Mont Blanc was entering the Halifax Harbor after being loaded in Brooklyn N.Y. with 2,300 tons of picric acid, a bomb component, 200 tons of TNT and 300 tons of high-octane gasoline for shipment to France for the war effort. Due to pilot error the Mont Blanc collided with the Norwegian vessel Imo. The collision set the picric acid ablaze and propelled the Mont Blanc towards the north end of the City of Halifax. The blaze eventually ignited the TNT and the ship exploded. The explosion was equivalent to 2.9 kilotons of TNT. It wiped out the entire north end of the city killing 2,000 people and wounding 9,000. Over 1600 buildings were destroyed. At the time it was the largest explosion ever to occur and was studied as part of the development of the first atomic bomb.

Amazingly on July 18, 1945 (yes today’s date) there was another munitions explosion in Halifax. When the war in Europe ended many ships used in the European theatre were being sent to Halifax to be refitted for action in the Pacific theatre. Thousands of tons of munitions were being off loaded from ships being retrofitted and stored in the Halifax munitions facility. A fire broke out on the Halifax docks near the munitions facility and eventually it led to the explosion of the munitions. Fortunately, the force and effect of the explosion was limited by the construction of the facility and there were only a few deaths and injuries as well as limited damage to the City.